The Reasonable Person - New York University Law Review

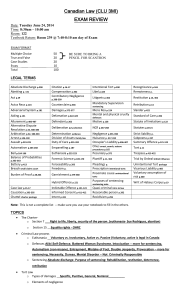

advertisement