Better Value, Fewer Taxpayer Dollars

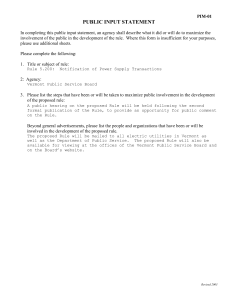

advertisement