Schoolchildren final.qxd

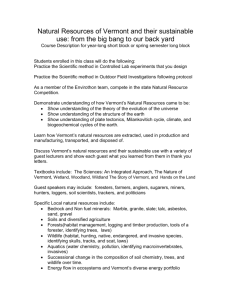

advertisement