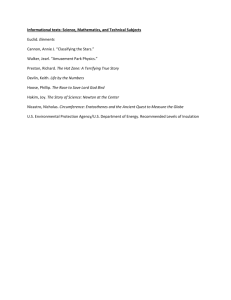

Gap in Personal Jurisdiction Reasoning: An

advertisement