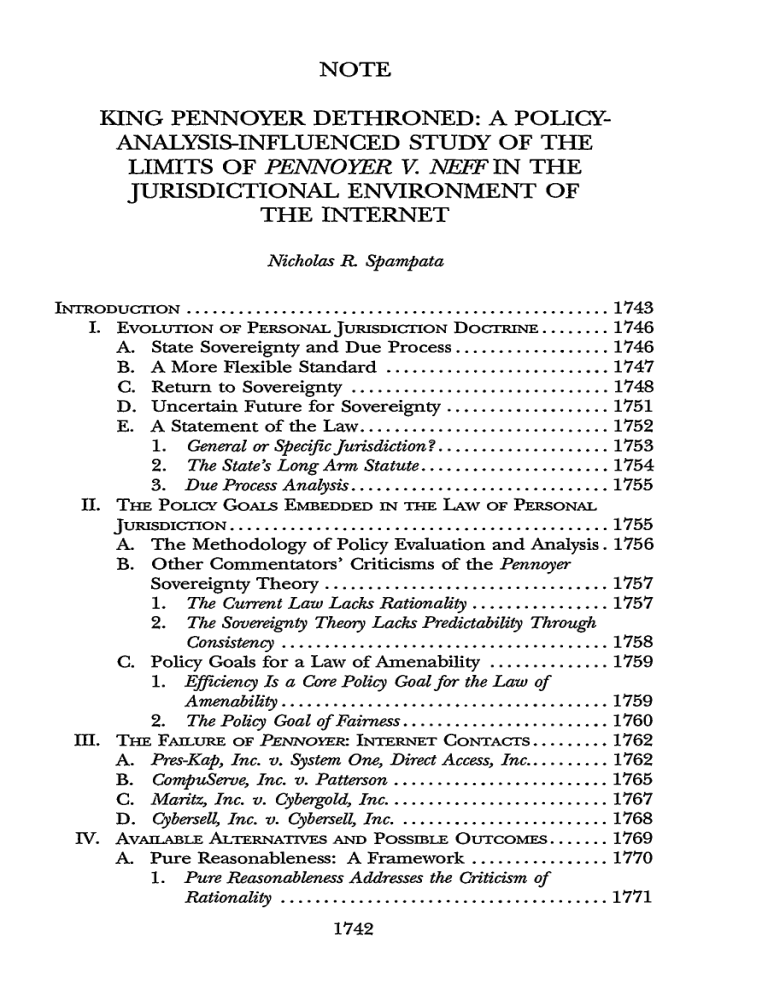

note king pennoyer dethroned: a policy- analysis

advertisement