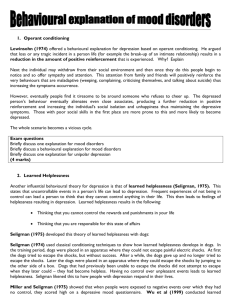

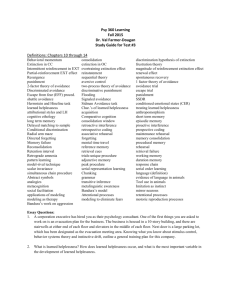

Learned Helplessness in Humans: Critique and Reformulation

advertisement