Robert R. McCormick and Near v. Minnesota

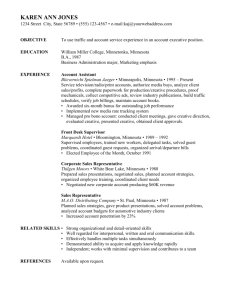

advertisement