Traditional Leadership and Independent - North

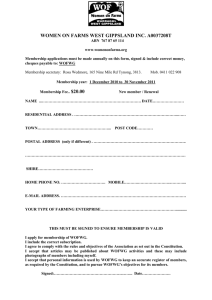

advertisement