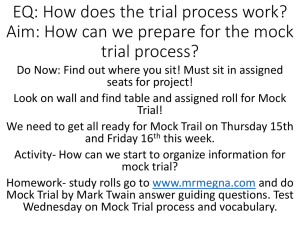

Putting on Mock Trials

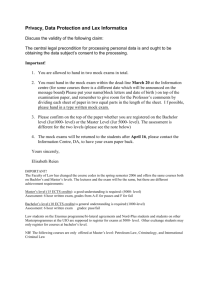

advertisement