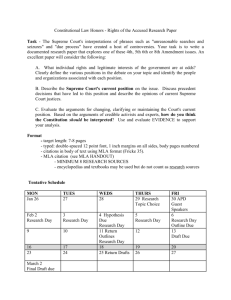

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE ARREST AND

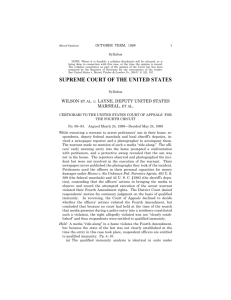

advertisement