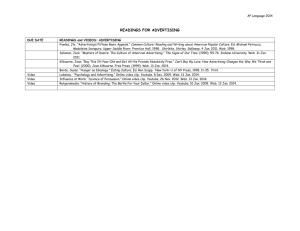

Fox

advertisement