Stripping the Veneer and Exposing a Symbol in Mendes's Cabaret

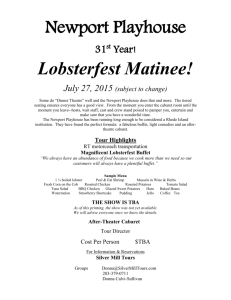

advertisement