a look at the ethical rules governing lawyers' campaign contributions

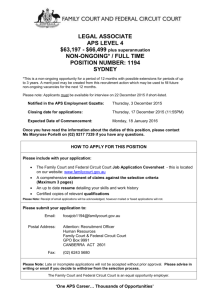

advertisement

JUDICIAL ELECTIONS AND COURTROOM PAYOLA: A LOOK AT THE ETHICAL RULES GOVERNING LAWYERS' CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS AND THE COMMON PRACTICE OF "ANYTHING GOES" Nancy M Olson* Introduction .................................................. I. The Current Landscape of Judicial Election Campaigns. II. What Ethical Rules Currently Govern Lawyers' Campaign Contributions to Judges? ................... A. No Prohibition Against Judicial Campaign C ontributions .................................... B. Duty of Candor to the Tribunal ................... C. Impartiality and Decorum of the Tribunal ......... D. Maintaining the Integrity of the Profession ........ E. Political Contributions to Obtain Appointments ... III. When Does Favor-Seeking Behavior Go Too Far? ...... A. Florida Bar v. Wheeler ............................ B. Neiman-Marcus Group, Inc. v. Robinson ............ C. Dean v. Bondurant ............................... D . In re Bolton ...................................... E. Review of General Case Principles ................. IV. Proposed Changes to the Model Rules: Addressing the "G ray Areas" . ........................................ A. Pay attention to what attorney-contributors are saying ............................................ B. Develop criteria for testing the legitimacy of attorney contributions ............................ C. Amend Model Rule 7.6 to encompass other forms of "pay to play" besides judicial appointments, and close the "uncompensated services" loophole ....... * 342 345 347 347 349 350 350 352 354 355 355 356 357 359 360 360 361 362 Nancy M. Olson is currently a Judicial Law Clerk to the Honorable Alicemarie H. Stotler, United UCLA 2001. would States District Judge for the Central District of California. She is a graduate of the School of Law, J.D. May 2008; and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, B.S., August She owes many thanks to Amanda Lee for her editing assistance with this Paper. She also like to thank her family for their continuing love and support. 342 CARDOZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J [Vol. 8:341 [ D. Change the standard under Rule 3.5(a) to a reasonable person standard ........................ 363 E. Strengthen judicial disqualification requirements when a judge receives contributions from attorneys who (1) contribute during the pendency of a case; (2) have served actively on the judge's campaign committee; or (3) ran as the judge's defeated opponent in the election .......................... 363 F. Make judicial recusal an option when no rules have been broken per se, but "impartiality may reasonably be questioned" ........................ 365 C onclusion ................................................... 365 INTRODUCTION It is no secret that candidates running for elected judicial office get most of their campaign contributions from attorneys. And, there is no question that it is both proper and desirable for attorneys to contribute to such election campaigns.' Attorneys are in a better position than the general public to understand what background and qualifications are necessary for good judicial candidates, and they have a right to support the candidates they believe are best for the job. There is also no doubt that the public, attorneys, and even judges to some extent, think campaign contributions cast serious doubt on the ability of judges to remain impartial when administering justice.2 The U.S. Supreme Court re1 MODEL CODE OF PROF'L RESPONSIBILITY EC 8-6 (1976); ABA Comm. on Prof l Ethics and Grievances, Formal Op. 189 (1938) ("It is proper that [lawyers] should (support wellqualified judges] ... in a proper and dignified manner."); See also AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION, TASK FORCE ON LAwyuERs' POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS, REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE TASK FORCE ON LAWYERS' POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS, ABA PART Two 27 (1998) [hereinafter TASK FORCE REPORT]. 2 See James Sample & David E. Pozen, Making JudicialRecusal More Rigorous, 46 JUDGES' J. 1, 2 (Winter 2007). Nationwide public opinion surveys taken from 2001 and 2004 show that over 70% of Americans believe that campaign contributions have "at least some influence" on judges' decisions in the courtroom. Only 5% believe campaign contributions have "no influence." According to the 2001 survey, only 33% of respondents believe the "justice system in the U.S. works equally for all citizens." Id.; see also Mark A. Behrens & Cary Silverman, The Case for Adopting Appointive JudicialSelection Systems for State CourtJudges, 11 CORNELL J. L. & PUB. POL'y 273, 275-76, 283 (Spring 2002) (citing a study that found 81% of Americans believe judges are influenced by campaign contributions and politics, as well as the fact that court personnel, attorneys, and judges generally share this belief; for example, 48% of Texas judges confessed they believe money has an impact on judicial decisions). 2010] JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA 343 cently dealt with this issue in Caperton v. A. T. Massey Coal Co. 3 The Court cautioned that when judicial campaign contributions lead to a high probability of bias, a party's due process rights may be violated if judicial recusal is not granted. Although the contributor at issue in Caperton was the CEO of a party in the case, the Court's holding speaks to a probability of bias that can occur from contributions arising from any donor. A few scholars have conducted empirical research to determine whether the skepticism relating to judicial bias is warranted. One study reveals a "remarkably close" correlation between one justice's vote on arbitration cases and his source of campaign funds.4 Another study shows that over a twelve-year period, more than 70% of the time, Ohio Supreme Court justices voted in favor of their contributors.5 While there is no way to determine whether "this is causation or mere correlation, many major contributors hope and assume it is the former." 6 According to one sitting state Supreme Court justice, "everyone interested in contributing has very specific interests. They mean to be buying a 7 vote. Whether they succeed or not, it's hard to say." The ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct ("Model Rules") and their various state counterparts are not entirely silent when it comes to prohibiting attorney conduct that may improperly influence the judiIn a 2002 written survey of 2,428 state trial, appellate, and supreme court judges, 26% said they believe campaign contributions have at least "some influence" on the judges' decisions while 46% said they believe contributions have at least "a little influence." Moreover, 56% of judges believe "judges should be prohibited from presiding over and ruling in cases when one of the sides has given money to their campaign." Id. 3 Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co., 129 S. Ct. 2252 (2009). 4 Sample & Pozen, supra note 2, at 2 (citing Stephen J. Ware, Money, Politics andJudicial Decision: A Case Study ofArbitration Law in Alabama, CAP. U. L. REv. 583, 584 (2002)). 5 Id. (citing Adam Liptak & Janet Roberts, Campaign Cash Mirrors a High Court's Rulings, N.Y. TIMES, Oct. 1, 2006, §1, at 1, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2006/lOO1/us/ 0ljudges.html). 6 Id. 7 Id. (quoting Justice Paul E. Pfeifer of the Ohio Supreme Court in Liptak & Roberts, supra note 5); see also Mark Andrew Grannis, Note, Safeguarding the Litigant's Constitutional Right to a Fairand ImpartialForum: A Due ProcessApproach to ImproprietiesArising From Judicial Campaign Contributionsfrom Lauyers, 86 MICH. L. REv. 382, 400 (Nov. 1987) (concluding that if one party is a large contributor to a judge, even if the judge has no reason to expect the contributions will stop after an adverse decision, the judge's sympathies will be altered); Bradley A. Siciliano, Attorney Contributionsin JudicialCampaigns: Creatingthe Appearanceoflmpropriety, 20 HOFSTRA L. REv. 217, 227 (Fall 1991) (discussing attorney contributions and stating, "[t]he idea is to further the giver's goal - to curry favor with the judge"); Michael J. Goodman & William C. Rempel, In Las Vegas, They're Playing With a Stacked JudicialDeck, L.A. TIMES, June 8, 2006, at 3 (according to one former state judge, if a case is a close call, asking judges to treat campaign contributing lawyers and non contributors the same is "asking for the superhuman"). 344 CARD OZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J [Vol. 8:341 [ ciary or create such an appearance. 8 However, as judicial election campaigns become increasingly more expensive and polarized, the rules seem inadequate to keep pace. Consider the following account: A group of lawyers decided to host a fundraiser for a local state judge running for reelection. Some of the lawyers had cases pending before the judge, including a case that was set for a crucial hearing four days after the fundraising event. To attract other donors, invitations were sent out touting, "A Lavish Buffet Dinner . . . catered by Big Bear's Premier Restaurant, [with] Food, Fun, Libations... [a] Sunset Cruise... [and] a Zoo Tour for the Little Ones." 9 The candidate himself attended the "lavish" event and the evening "blossomed into a festival of champagne, lobster and money.., nearly $30,000 ... [was dropped] into a crystal punch bowl."' One of the lawyers sponsoring the event, also scheduled to appear before the judge four days later on behalf of the plaintiffs, explained his donation to the judge: "Giving money to a judge's campaign means you're less likely to get screwed.... A $1,000 contribution isn't going to buy special treatment. It's just a hedge against bad things happening."1 1 When the defense team, who was from out of state and contributed nothing to the judge's campaign, heard about the gala they filed a motion asking the judge to withdraw from the case. They argued that the timing of the campaign event was "too close." 12 The judge refused, citing "no bias or prejudice" on his part. 13 The defense team then asked for a delay, which the judge also refused. The case went to trial and the judge ordered the defendant to pay $1.5 million in damages. The defendant and his attorneys were appalled; they said they would not be back for more "hometown justice."1 4 This series of events occurred last time Nevada State Judge Gene T. Porter ran for reelection. Local Las Vegas attorneys shrugged off the facts, saying, "[t]his is a juice town . ... Financial contributions get you juice with a judge - an 15 If you have juice, you get different treatment." in . . 8 See infra Part II for a discussion of the various Model Rules of Professional Conduct that may be implicated by attorney campaign contributions to judicial candidates. 9 Goodman & Rempel, supra note 7, at 1. 10 Id. 11 Id. 12 13 14 15 Id. Id. Id. Id. (internal quotations omitted). 20101 JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA 345 Presently, most of the discussion surrounding improper conduct in judicial election campaigns has focused on whether the candidates running for office have broken any laws or ethical rules. 16 This Paper turns to examine an often overlooked aspect of judicial election campaigns. Namely, what limits are placed on appropriate attorney conduct during and after judicial election campaigns; and, are lawyers simply getting away with too much? Part I briefly explains the prevalence of judicial election campaigns and looks at some of the trends likely spurring ethically questionable behavior among attorney campaign contributors (and judicial candidates). Part II examines the ethical rules that govern lawyers' conduct with regard to judicial campaign contributions and improper influence on the judiciary. Part III reviews examples of past conduct on which a court has ruled, including instances of both punished and unpunished conduct, in order to determine where the line is currently drawn. Part IV then provides a proposal for useful changes to the Model Rules, as well as improvements for enforcing the rules, in order to curb the frequent influence-seeking behavior of attorneys, thereby preserving the administration of justice. Curbing this behavior will also play a positive role in the courtroom because the "probability of bias" that the Supreme Court warned of in Caperton will be minimized, ensuring that parties are afforded the right to due process of law. I. THE CURRENT LANDSCAPE OF JUDICIAL ELECTION CAMPAIGNS The United States is virtually alone in its practice of electing state judges. 17 Most states in the U.S. use some form of election for selecting 16 See MODEL CODE OF JUDICAL CONDUCT Canon 5 (2000) (pertaining to judicial elec- tions, this Canon applies to "all incumbent judges and judicial candidates," encompassing both current judges and non-judge candidates). The CJC, of course, applies to the conduct of elected judges once they are in office. For articles discussing problematic behavior among judicial candidates and the problems with electing judges, see generally Grannis, supra note 7; Behrens & Silverman, supra note 2; Leona C. Smoler & Mary A. Stokinger, Note, The Ethical Dilemma of CampaigningforJudicialOffice: A ProposedSolution, 14 FoRDHAM URB. L.J. 353 (1996); Roy A. Schotland, Elective Judges' Campaign Financing: Are State Judges' Robes the Emperor's Clothes of American Democracy?, 2 J.L. & POL'Y 57, 91-93 (1985) [hereinafter Elective Judges' Campaign Financing]; David B. Rottman & Roy A. Schotland, What Makes JudicialElections Unique?, 34 Loy. L.A. L. REV. 1369 (2001); Hon. Hugh Maddox, Taking Politics Out ofJudicialElections, 23 Am. J. TRIAL. ADvoc. 329, 335 (1999). 17 COURT REVIEW, AN INTERVIEW WITH Roy SCHOTLAND 12, 16 (Fall 1998), available at http://aja.ncsc.dni.us/courtrv/cr35-3/CR35-3Schodand.pdf [hereinafter SCHOTLAND INTERVIEW] (discussing how Switzerland elects some of their judges and that the former Soviet Union used the same practice). 346 CARDOZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J [Vol. 8:341 [ both trial and appellate judges. 8 Currently 87% of all state judges stand for some form of election, either contestable or retention. 9 Modern judicial campaigns are frequently supported by plaintiffs' lawyers, and other narrower interest groups, who often do not disclose their sources of funding.2 ° As partisanship and special interest group participation increases, the tone of judicial elections becomes "noisier, nastier and costlier,"21 severely undermining the moral authority of the courts.22 In 2000, a Michigan Republican television ad attacked a judge for upholding a light sentence while flashing the word "pedophile" across the screen.23 The Michigan Democrats featured an ad asserting that incumbent justices had "ruled against families and for corporations 82% of the time," a claim that the Detroit Free Press found to "border[ I on bogus." 2' The difference in tone between judicial election cam- paigns and campaigns for other elected office has all but disappeared with judicial campaigns featuring "accusations of race baiting, dirty politics, catering to rich trial lawyers and abdication to business inter26 ests." 25 For attorneys, these hostile campaigns can be a "minefield. Whatever you do in response to donation requests, you're probably going to offend "someone you can't afford to offend; and you will spend a 27 small fortune doing it." Money plays an enormous role in judicial election campaigns. One California state judge quipped, "my 'reasons for winning'.., are as 18 Behrens & Silverman, supra note 2, at 277. 19 SCHOTLAND INTERVIEW, supra note 17, at 13. 20 Sample & Pozen, supra note 2, at 2. This scenario also brings to mind a question of whether attorneys must disclose contributions they make to special interest groups who then contribute to judicial campaigns. Although this topic is outside the scope of this Paper, it seems likely that many of the same ethical rules discussed infra Part II are similarly implicated. 21 Behrens & Silverman, supra note 2, at 274-75 (citing Rottman & Schotland, supra note 16, at 1373 n.5). 22 Id. at 75. 24 Id. Id. 25 Id. at 283. One reason for this is a recent Supreme Court decision holding that "an- 23 nounce clauses," which prohibit judicial candidates from announcing their views on disputed issues, to violate the First Amendment. See generally Republican Party of Minnesota v. White, 536 U.S. 765 (2002); Behrens & Silverman, supra note 2, at 283 (quoting William Glaberson, Fierce Campaigns Signal a New Era for State Courts, N.Y. TIMES, June 5, 2000, at Al). 26 Behrens & Silverman, supra note 2, at 280. 27 Id.; see also Grannis, supra note 7, at 408. Attorneys surveyed stated that refusing to contribute to a judge's campaign would jeopardize the interest of their firms and clients appearing in that judge's courtroom. Id. Some attorneys also reported sending checks to the winner after a judicial election to "cover" themselves. 2010] JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA 347 follows: (1) Money; (2) Organization; (3) An early start; (4) Money; (5) An 'excellent' candidate; (6) A weak opponent; (7) Excellent public relations and use of media advice; (8) Money; (9) Luck. ' 28 Not only is money on top of the list, outranking all of the other factors - including the quality of the candidate - but it appears three times, a clear indication of money's influence on the success of judicial campaigns. During the 1994-1998 period, candidates running for seats on state supreme courts raised a total of $73.5 million.2 9 Only a few years later, during the 2000-2004 period, candidates raised a total of $123 million, a 67% increase.3 ' Nineteen candidates broke the million-dollar mark during the former period while thirty-seven did during the latter period. 3 The amount of money spent on judicial election campaigns "strongly suggests that campaign contributors are hoping to influence a judicial philosophy through their giving."'32 As money increases in importance to judicial election campaigns and lawyers remain the largest group of campaign contributors, the adequacy of the ethical rules guiding lawyers' behavior during judicial election campaigns should continually be assessed. II. WHAT ETHICAL RULES CURRENTLY Govis LAwYERs' CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS TO JUDGES? A. No ProhibitionAgainst Judicial Campaign Contributions As a threshold matter, it is important to understand that no broad prohibition exists on attorney campaign contributions to judicial candidates. The Model Rules do not give much attention to this specific topic. In fact, the Model Rules only address campaign contributions in one limited situation, although they are addressed more thoroughly for judicial candidates in the ABA Model Code of Judicial Conduct ("CJC"). 33 The general rule is that anyone may donate a reasonable 28 Grannis, supra note 7, at 398 (quoting Elective Judges' CampaignFinancing,supra note 16, at 155). 29 Sample & Pozen, supra note 2, at 1. 30 Id. 31 Id. 32 Behrens & Silverman, supra note 2, at 279. 33 See MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 7.6 (2000) (discussing campaign contribu- tions made for the purpose of obtaining judicial appointments); see also MODEL CODE OF JUDICItAl CONDUCT Canon 3B(2) (2000) (stating that judges must not be swayed by partisan interests or fear of criticism); Canon 3C(4) (instructing a judge to exercise the power of appointment impartially and on the basis of merit); Canon 3C(5) (prohibiting a judge from appointing 348 CARDOZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J [ [Vol. 8:341 amount of money or time to a judicial campaign as long as the contributor does not expect to receive any direct benefit if the candidate is elected.3 The ABA's Report and Recommendations of the Task Force on Lawyers' Political Contributions states that "[l]awyers ... have an obligation to support good judges," and then asks, without lawyers, "where are the judges going to get [enough] money" to run their election campaigns? 35 Even lawyers with cases before, or which are likely to come before, a judicial candidate may contribute to the candidate, so long as any solicitation done by the campaign does not mention "any particular pending or potential litigation." 36 "Because lawyers may be better able than laymen to appraise accurately the qualifications of candidates for judicial office, it would not be appropriate ... to prohibit solicitation of lawyers who may appear before the candidate." 37 According to Professor Roy Schotland, the reporter for the ABA Task Force, As long as the rules are as they are, anybody who faults plaintiffs' lawyers on the one hand or the defense side... on the other hand, is either being silly or hypocritical .... I don't mean for one second to say that these people are doing anything wrong when they participate. The only thing [that] would be wrong is if they give sums that are illegal or they launder money and so forth, and I'm not aware of any 38 such problems in judicial races. Therefore, under the Model Rules, attorneys are free to donate to judicial candidates as they like, so long as they are not seeking judicial favor. a lawyer who has made more than a certain amount in campaign contributions); Canon 3E(1) (calling for disqualification when a judge has a personal bias toward a party or his lawyer, or has received more than a certain amount in campaign contributions from a party or his lawyer). 34 James J. Alfini & Terrence J. Brooks, Perspectives on the Selection of FederalJudges: Ethical Constraints on JudicialElection Campaigns:A Review and Critique of Canon 7, 77 Ky. L.J. 671, 711 (1989). 35 SCHOTLAND INTERVIEW, supra note 17, at 15. 36 Alfini & Brooks, supra note 34, at 709 (citing Ethical Guidelines for Judicial Campaigns, 4B SDCL app. ch. 12-9 (1982)). 37 Id. 38 SCHOTLAND INTERVIEW, supra note 17, at 14. 2010] JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA B. 349 Duty of Candor to the Tribunal Under Model Rule 3.3, lawyers have a duty of candor to the tribunal. This means that lawyers must avoid conduct that undermines the integrity of the adjudicative process.4" This is "a special obligation to protect a tribunal against criminal or fraudulent conduct . . . such as bribing, intimidating or otherwise unlawfully communicating with a... court official ... or failing to disclose information to the tribunal when required by law to do so." 4 In the context of judicial election campaigns, this rule may be implicated frequently. 39 Obviously, a lawyer must not use support of a judge's reelection campaign as a bribe to achieve a particular result in a proceeding before the court.4 2 If a lawyer is aware that such behavior has occurred, the remedial measures called for in the Comment to this rule include disclosure to the tribunal "that a person, including the lawyer's client, intends to engage, is engaging or has engaged in criminal or fraudulent conduct related to the proceeding."4 3 Under the disclosure requirement, a lawyer technically has a duty to tell the tribunal when the lawyer knows that he himself has engaged in fraudulent conduct (e.g. improperly trying to influence someone on the campaign committee). This is unlikely to happen, though, because if a lawyer has engaged in such conduct, he is unlikely to willingly expose it in open court. Although it is easy to think of clear-cut examples of a lawyer bribing a judge outright with campaign contributions, the reality of what happens in judicial election campaigns is often much more nuanced. A lawyer may choose to join a campaign committee to show support for a judicial candidate, meanwhile using illicit campaign tactics in favor of the candidate or against the opponent. A lawyer may break local rules governing the timing and amount of allowable donations or rules governing solicitation. A party may also do any of the above in an attempt to influence the proceeding, and if his or her lawyer discovers this, the duty of candor to the tribunal requires that the conduct be disclosed. Because this rule only pertains to criminal or fraudulent conduct, it does 39 MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 3.3 (2000). 40 MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 3.3 cmt. (2000). 41 Id. 42 See infra Part II.C (discussing Model Rule 3.5). This type of influence may also simulta- neously violate the prohibition on improper ex parte communications. 43 Id. 350 CARDOZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J [Vol. 8:341 [ nothing to address the gray areas of judicial election campaigns where lawyers seek judicial favor without committing a crime or fraud. C. Impartiality and Decorum of the Tribunal Under Model Rule 3.5, "[a] lawyer shall not: (a) seek to influence a judge . . . by means prohibited by law; [or] (b) communicate ex parte with such a person during the proceeding unless authorized to do so by law or court order . . . .", Improper influence of a tribunal may be proscribed by criminal law or addressed in the CJC.4 5 Lawyers are required to avoid being a part of any candidate's violation of the CJC.46 For example, a lawyer may not offer a gift to a judge under Model Rule 3.5 unless it would be proper for the judge to accept the gift under the CJC. Under this Rule, if a lawyer contributes to a judge's election campaign, it would be improper for the lawyer to seek favorable influence by speaking to the judge ex parte to remind the judge about the contribution or ask whether the judge found the contribution helpful. On the other hand, even if a lawyer has not yet contributed, it would likewise be improper to imply to the judge that if the case goes away, the lawyer can free up time and resources to donate to the judge's campaign. D. Maintaining the Integrity of the Profession Under Rule 8.2(a), regarding judicial and legal officials, a lawyer must not "make a statement that the lawyer knows to be false or with reckless disregard as to its truth or falsity" about the qualifications or integrity of a judge or candidate for judicial office.4 7 A lawyer would not disparage the integrity of the candidate whom he or she is supporting, but he might make a false statement about the opponent to help the favored candidate. While lawyers are welcome to express their honest and candid opinions of judicial candidates because these assessments are useful in evaluating the professional or personal fitness of a candidate, "false statements by a lawyer can unfairly undermine public confidence in the administration of justice."48 This Rule is likely implicated most frequently in partisan judicial elections, where each candidate runs on a party ticket. Because these types of campaign attack methods, as de44 MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT 45 MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT 46 Id.; see also infra Part II.D (discussing 47 MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT 48 MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 3.5 (2000). R. 3.5 cmt. (2000). Model Rule 8.4). R. 8.2(a) (2000). R. 8.2(a) cmt. n.1 (2000). 2010] JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA 351 scribed in Part I, are becoming quite common, it is questionable whether this Rule is being strictly enforced, or even generally observed. In the larger scope of a lawyer's duty to the profession, Rule 8.4, governing misconduct, has many implications for attorney conduct regarding judicial campaign contributions. The entire Rule is quoted below because each subsection proscribes conduct that may arise in relation to judicial campaign contributions. It is professional misconduct for a lawyer to: (a) violate or attempt to violate the Rules of Professional Conduct, knowingly assist or induce another to do so, or do so through the acts of another; (b) commit a criminal act that reflects adversely on the lawyer's honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer in other respects; (c) engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation; (d) engage in conduct that is prejudicial to the administration of justice; (e) state or imply an ability to influence improperly a government agency or official or to achieve results by means that violate the Rules of Professional Conduct or other law; or (f) knowingly assist a judge or judicial officer in conduct that is a violation of applicable rules of judicial conduct or 49 other law. Subsection (a) is a catchall provision that says breaking a Model Rule is lawyer misconduct. Therefore, if any of the scenarios described above in Parts II.A through C occur, in addition to breaking or attempting to break one or more rules, the violation also constitutes Rule 8.4 misconduct. Subsections (b) and (c) may be implicated if a lawyer violates election law to help a particular judicial candidate win. Subsection (d) may be implicated if a lawyer provides campaign contributions or other support in conjunction with a desire to influence a proceeding before a candidate.5 0 Subsection (e) may come into play if a lawyer tries to obtain a new client or reassure an existing client by claiming the lawyer can obtain a desired outcome in a particular case. Note that subsection (e) requires only that a lawyer imply such an influence, which is a relaxed standard compared to other rules that require actual intent to improperly influence a judge or proceeding. Subsection (f) is also a catchall provision providing that any time a lawyer tries to influence a 49 MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 8.4 (2000). 50 This subsection of the Rule would ideally capture situations such as those described in and Avery v. State Farm (Tex. Civ. App. 1987) S.W. 2d 768 v. Pennzoil Co., 729 Texaco, Inc. Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 835 N.E.2d 801 (Ill. 2005). See infra notes 105, 113. 352 CARDOZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J [Vol. 8:341 judge through campaign contributions, one or more rules under the CJC may be broken, which automatically constitutes attorney miscon51 duct under Rule 8.4. E. Political Contributions to Obtain Appointments The Model Rules only specifically mention the topic of political contributions in Rule 7.6. The Rule states that "[a] lawyer or law firm shall not accept a government legal engagement or an appointment by a judge52 if the lawyer or law firm makes a political contribution or solicits political contributions for the purpose of obtaining or being considered for that type of legal engagement or appointment." 53 It is important to note that in order for a lawyer to violate this Rule, he must make the contribution for the purpose of obtaining or being considered for an appointment. 54 This is likely a very hard standard to prove, as lawyers likely do not send letters with their contributions directly asking for appointments. The Comment to this Rule emphasizes the principle that "[1lawyers have a right to participate fully in the political process, which includes making and soliciting political contributions to candi51 See also supra Part II.C for a discussion of Rule 3.5. 52 The term "appointment by a judge" means an appointment to a position such as referee, commissioner, special master, receiver, guardian or other similar position that is made by a judge. However, it does not include "(a) substantially uncompensated services; (b) engagements or appointments made on the basis of experience, expertise, professional qualifications and cost following a request for proposal or other process that is free from influence based upon political contributions; and (c) engagements or appointments made on a rotational basis from a list compiled without regard to political contributions." MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 7.6 cmt. n.3 (2000). 53 MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 7.6 (2000). 54 According to the Comment for Rule 7.6, Political contributions are for the purpose of obtaining or being considered for a government legal engagement or appointment by a judge if, but for the desire to be considered for the legal engagement or appointment, the lawyer or law firm would not have made or solicited the contributions. The purpose may be determined by an examination of the circumstances in which the contributions occur. For example, one or more contributions that in the aggregate are substantial in relation to other contributions by lawyers or law firms, made for the benefit of an official in a position to influence award of a government legal engagement, and followed by an award of the legal engagement to the contributing or soliciting lawyer or the lawyer's firm would support an inference that the purpose of the contributions was to obtain the engagement, absent other factors that weigh against existence of the proscribed purpose. Those factors may include among others that the contribution or solicitation was made to further a political, social, or economic interest or because of an existing personal, family, or professional relationship with a candidate. MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 7.6 cmt. n.5 (2000). JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA 2010] 353 dates for judicial and other public office." 5 5 When a lawyer makes a contribution only in hopes of receiving a judicial appointment, however, "the public may legitimately question whether the lawyers engaged to perform the work are selected on the basis of competence and merit.' 56In such a circumstance, the integrity of the profession is undermined." It is unclear why the only attorney favors explicitly identified and prohibited by the Model Rules with respect to campaign contributions are judicial and political appointments. 57 There are other ways a judge could make a lawyer's job or life easier and there appears to be a gaping hole in this Rule where other improper motivations behind campaign contributions should also be prohibited. Moreover, a review of the definition of "political contribution" reveals an implicit flaw in the appointment-seeking conduct sanctioned by this rule: The term "political contribution" denotes any gift, subscription, loan, advance or deposit of anything of value made directly or indirectly to a candidate, incumbent, political party or campaign committee to influence or provide financial support for election to or retention in judiFor purposes of this Rule, the cial or other government office .... term "political contribution" does not include uncompensated services.58 This definition explicitly recognizes that influencing the election of a candidate to political office is allowed. This is an important distinction to draw between proper "influence" of an election (i.e. campaigning for your favorite candidate) and conduct that rises to the level of "improper influence" of ajudge, as discussed in Rule 3.5 above.5 9 The definition also explicitly excludes uncompensated services, which would seem to include any volunteer service given to a candidate's election campaign in the form of educating voters, holding campaign events, and serving on a campaign committee, among others. This appears to be an intended loophole in the definition because this type of attorney behavior might ultimately curry more favor with a judge for case appoint55 MODEL RuLEs OF PROF'L CONDUCT 56 R. 7.6 (2000). Id. 57 If a lawyer makes or solicits a political contribution under circumstances that constitute bribery or another crime, Rule 8.4(b) is implicated. See MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 7.6 cmt. n.6 (2000). For a discussion of Rule 8.4(b), see supra Part II.D. 58 MODEL RULEs OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 7.6 (2000); see also supra Part II.E. 59 See supra Part II.C. CARDOZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J 354 [ [Vol. 8:341 ments or scheduling. 60 So long as attorneys do not solicit contributions as part of their "uncompensated services," it appears that under this rule, they are allowed to donate such services for the purpose of obtaining appointments. This seems contrary to the heart of the rule because it allows lawyers to contribute time and effort to a judicial campaign for the purpose of seeking an appointment. This type of uncompensated and non-solicitation related activity goes unpunished. This is illogical because personal services may easily be more valuable to a judicial candidate than monetary solicitation or donation, and therefore be more susceptible to influencing a judge. A judge is much more likely to remember favorably her campaign secretary than the name of a single donor on a list of many.6 1 Although a review of the Model Rules seems to make clear what sorts of attorney behavior related to judicial campaign contributions is prohibited, gray areas often emerge when applied to real-world cases. III. WHEN DOES FAVOR-SEEKING BEHAVIOR Go Too FAR? This Part provides a brief overview of select cases addressing the propriety of lawyers' campaign contributions and whether involvement in a campaign is enough to warrant judicial recusal or disqualification. It examines both punished and unpunished behavior in an attempt to measure where the line is currently drawn. Although this discussion focuses on lawyers' conduct, it also analyzes rules for judicial recusal and disqualification. When a judge's behavior regarding campaign contributions or favoritism of a party is called into question, it is important to remember the duties of lawyers on the receiving end of the conduct and ask whether they were or should have been punished as well. 60 Goodman & Rempel, supra note 7, at 4. According to former Nevada prosecutor Ulrich Smith, a $500 to $1,000 contribution might not get you a favorable ruling, but might help you "grease the skids ... [to] get your case called first." Id. If attorneys can move up on the docket with small donations, having a personal relationship with a judge will likely accomplish even more. 61 Another instance in which support is likely more valuable than money is when a highprofile attorney gives an endorsement to a judicial candidate. This could not only have the power to draw contributions from others, but might play an important roll in the tide of the election. See Siciliano, supra note 7, at 224. 2010] JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA A. 355 Florida Bar v. Wheeler In Florida Bar v. Wheeler, the Florida State Bar brought an action against attorney Kent S. Wheeler for misconduct. 62 A referee appointed to the case found that Wheeler violated a number of state bar rules when he entered into a payment scheme with judges by providing them with campaign contributions, commissions, and loans in exchange for public defender positions.6 3 Wheeler pleaded guilty in exchange for immunity from criminal corruption charges. The referee recommended disbarment, and the Florida Supreme Court upheld the recommendation.6 4 It is unclear whether the judges in this case were also punished, but in light of the fact that Wheeler was caught as part of a broader criminal corruption probe, they likely were. This case represents a clear case of "pay to play," whereby an attorney provides a quid pro quo. Here, it was campaign contributions and other payments to judges in exchange for lucrative court appointments. This type of arrangement is specifically prohibited under Model Rule 7.6, as discussed above.65 B. Neiman-Marcus Group, Inc. v. Robinson During a hearing on the petitioners' motion for partial summary judgment, the trial judge informed the parties that the respondents' attorney served as his campaign treasurer during a recent reelection campaign.6 6 Petitioners filed a motion to disqualify the judge and respondents argued that disqualification was unnecessary because the judge's campaign ended before the disqualification motion was filed. The trial court denied the motion as legally insufficient.6 7 The appellate 63 Fla. Bar v. Wheeler, 653 So. 2d 391, 391 (Fla. 1995). Id. 64 The conduct that the referee found to be in violation of state ethics rules included: com- 62 mission of an act that is unlawful or contrary to honesty and justice, criminal misconduct, and engaging in conduct in connection with the practice of law that is prejudicial to the administration of justice. Interestingly, charges were not brought against Wheeler for knowingly assisting a judicial officer in conduct that was in violation of state rules of judicial conduct. Id. 65 See supra Part II.E. Note that although the judges in Wheeler were complicit in the payment scheme, a less clear-cut case would arise if an attorney gave a contribution for the purpose of obtaining an appointment, but the motive could only be inferred from circumstantial evidence. 66 Neiman-Marcus Group, Inc. v. Robinson, 829 So. 2d 967, 968 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2002). 67 Id. 356 CARD OZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J. [Vol. 8:341 court subsequently reversed the ruling. 68 The appellate court recognized that a judge's disqualification is not warranted merely because a lawyer who appears before him has contributed to or been involved in his campaign. 69 The moving party must show that the attorney and judge enjoy a "specific and substantial political relationship. ' 7' Given the fact that the judge selected the attorney for the special role of campaign treasurer, and petitioners filed the motion only a few days after the close of the campaign, the appellate court held that respondents had not dispelled the appearance of impropriety. 7 1 The case was remanded for 72 disqualification. This case reiterates the general rule that contributing or merely being involved in a judicial election campaign is not enough to question a judge's impartiality or an attorney's motives for supporting him. 73 At the same time, it also demonstrates that a court may find that the appearance of impropriety is strong enough to warrant disqualification of a judge even without a direct showing of improper influence.74 This ruling highlights the need for courts and members of the profession to preserve a just and ethical judicial system at the cost of sometimes questioning judges' motives. A judge in this type of situation may feel that she is being unfairly accused of impropriety and may truly believe that she can remain impartial. Yet despite these concerns and the expense of delaying the case, questioning a judge's motives will create a more trustworthy judicial system in the end. C. Dean v. Bondurant In a case before the Kentucky Supreme Court, petitioners sought the disqualification of a Supreme Court justice on the ground that his impartiality was compromised because respondents and their attorneys had contributed to the justice's last election campaign. 75 During the justice's campaign, members of the respondents' law firm hosted a fundraiser in support of the campaign. 76 The justice decided to grant the 68 69 Id. Id. Id (citing Caleffe v. Vitale, 488 So. 2d 627, 629 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1986)). Id. at 968. Id. at 969. 73 Id.at 968. 74 Id. at 968-69. 75 Dean v. Bondurant, 193 S.W.3d 744, 746 (Ky. 2006). 76 Id. at 744. 70 71 72 2010] JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA 357 motion to recuse, but in doing so he reiterated the uniform rule that a mere campaign contribution was not sufficient grounds for recusal.77 However, the justice found more than a mere campaign contribution at issue. Not only was one of the parties a law firm, but many of its attorneys made numerous campaign contributions. Considering these facts collectively, the justice determined that the contributions were not minimal.7 8 This case sets forth a totality of the circumstances test under which facts surrounding the relationship between the judge and the donors should be analyzed to see if the judge's impartiality may reasonably be questioned. 79 Note that when recusal is proposed, the question is whether the judge was improperly influenced such that he or she can no longer remain impartial.8" Conversely, attorneys at the source of the influential conduct (e.g., contributions, fundraiser parties) are not similarly scrutinized as to the ethicality of their behavior. Perhaps if attorneys had to answer for their behavior at this stage as well, they may be more apt to avoid the appearance of impropriety in campaign contributions and activities. D. In re Bolton Attorney Bolton approached a judge in the parking lot of the courthouse and asked the judge's law clerk to leave the two alone.8 1 Once they were alone, Bolton asked the judge how he could give a "gift" to a judge.82 The judge advised Bolton that judges cannot accept gifts. Bolton then said he wanted to give a monetary contribution to a judge. 83 The judge informed him of the limitations and procedural requirements for giving a campaign contribution. 84 Bolton then made a reference to a personal injury case he had pending in the judge's court and then asked how soon the case could be put on the docket because his client was "badly hurt."8 5 Immediately after this, Bolton moved 77 Id. at 751. 78 Id.at 752. Compare this case with the example given in the Introduction (the fundraiser given for Judge Gene T. Porter) and Texaco, Inc. v. Pennzoil Co., 729 S.W. 2d 768 (Tex. Civ. App. 1987), discussed infra, note 105, neither of which resulted in recusal. 79 Dean 80 Id. v. Bondurant, 193 S.W.3d at 752. 81 In re Bolton, 820 So. 2d 548, 548 (La. 2002). 82 83 84 85 Id. Id. Id. Id. 358 CARDOZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J [[Vol. 8:341 closer to the judge and asked, "[w]hat if I wanted to give you $5,000?86 Bolton then traced a box in the air with his hands and told the judge, "[t]his [conversation] is just between me and you." 8 7 The judge immediately left the conversation. When Bolton later appeared before the judge in court, he apologized for any "misunderstanding" that may have resulted from the conversation.8 9 The judge reported Bolton's conduct, and after a hearing, the Disciplinary Board adopted the Hearing Committee's recommendations, finding no clear and convincing evidence of bribery.90 However, the Committee found that the ex parte communication was improper, created an appearance of impropriety, and caused potential interference with a legal proceeding pending before the judge's court. 9 ' Therefore, Bolton's conduct was prejudicial to the administration of justice, and the court reprimanded him with a one-year suspension from the practice of law.92 One dissenting justice argued that, The Court's failure to call this blatant and egregious conduct what it is, e.g., attempted bribery of a judge, is regrettable. Further, if the evidence presented in this case does not amount to clear and convincing evidence of attempted bribery, the Court is de facto creating a burden of proof which will be all but impossible for the Office of Disciplinary Counsel to meet.9 Another dissenting justice was outraged by the lenient punishment, stating, The majority characterizes the evidence as simply an inappropriate ex parte communication with the judge. I disagree and find the evidence supports that Bolton's conduct was an attempt to affect the outcome of his pending case with the judge. This conduct falls within [the ABA Standards calling for] "disbarment . . . when a lawyer ... makes an ex parte communication with a judge ... with intent to affect the Id. Id. 88 Id. 89 Id. at 549. 90 Id at 551. 86 87 91 Id. 92 93 Id. at 554. Id. at 555 (Victory, J., dissenting). 2010] JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA 359 outcome of the proceeding .... " Accordingly, I would impose dis94 barment as the baseline sanction. The multiple, vehement dissents in this case show clear disagreement on where to draw the line determining when influence-seeking behavior rises to a level warranting disbarment. Although the attorney in this case was punished with a one-year sanction, the dissenting justices make a strong argument that this sanction was far too lenient given the indications that Bolton alluded to bribery and referenced a pending case during the ex parte communication. E. Review of General Case Principles Although this section has discussed only four cases, each highlights a specific campaign contribution principle regarding what types of attorney conduct, attorney-judge relationships, and attorney-judge communications are proper under various ethics rules. 95 The following broad spectrum is based on the principles outlined above: SPCRMO CODUT RLTOSHI While it is clear that bribery is not allowed under the rules while campaign contributions are, this spectrum does little to address the gray 94 Id. at 556 (Knoll, J., dissenting). 95 Although the cases discussed above refer to state ethics rules, the state rules are patterned after the Model Rules (current as of the date of each case), as is clear by comparison to the Model Rules and CJC Canons discussed supra Parts II.A through II.E. CARDOZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J 360 [ [Vol. 8:341 areas in between. Given the limitations of the existing Model Rules and the problematic conduct discussed in this Paper, the next Part proposes ways to regulate other problematic attorney behavior. IV. PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE MODEL RULES: ADDRESSING THE "GRAY AREAS" In response to the concern that lawyers' campaign contributions to judges will detract from a judge's ability to remain impartial, an array of sweeping proposals has been suggested, including completely banning lawyer contributions in favor of public financing. 96 The pros and cons of public financing are outside the scope of this .Paper and the suggestions offered below do not go so far as to ban lawyer campaign contributions. The below suggestions aim to address many of the problems identified in Parts I through III. A. Pay attention to what attorney-contributorsare saying Throughout the discussion, myriad reasons attorneys cite for giving judicial campaign contributions have been discussed, such as: to avoid "get[ting] screwed,"' 97 to "hedge," 98 to buy "favorable court dates on crowded dockets." 99 These reasons may not be quid pro quos that rise to the level of bribery, but they should be addressed. As the dissent in Bolton argued, if the bar is set too high, then ethics boards will have "too heavy [a] burden of proof which will be all but impossible [to] meet" with regard to improperly motivated judicial campaign contributions.1"' Under Model Rule 3.5, improper motivations of any kind should be recognized as seeking "improper influence on a tribunal" and sanctioned 96 Siciliano, supra note 7, at 232-33. Some states have suggested creating a "trust fund" that would pass on attorney contributions to specific candidates without telling the candidates who made the contributions. Id. While such plans were enthusiastically endorsed in Detroit, Michigan and Dade County, Florida, interest waned or other problems arose with the IRS. Id. at 233. A related proposition was floated in Louisiana to create a "judicial campaign matching fund." See Wayne J. Lee, Department:President'sMessage:JudicialIndependence:Perception & Reality, 51 L.A.B.J. 82, 83 (Aug./Sept. 2003). In lieu of direct attorney judicial contributions, revenues from "an annual assessment from lawyers" would be used to fund judicial campaigns. Id. 97 Goodman & Rempel, supra note 7, at 1. 98 Id. 99 Id. at 4. 100 In re Bolton, 820 So. 2d 548, 555 (La. 2002) (Victory, J., dissenting); see also supra Part III.D. Although the question in Bolton was whether there was enough evidence of bribery to disbar the attorney, the question of whether an attorney's motives are enough to warrant any punishment is likewise applicable in other situations when an attorney seeks favor from a judge. JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA 2010] 361 accordingly."t ' This is notwithstanding the fact that attorneys argue "this is the way it's always been done - fast and loose," or that such tactics are necessary because their jurisdiction is like "the wild, wild West." 102 B. Develop criteriafor testing the legitimacy of attorney contributions In some ways, we have seen that courts already use a totality of the circumstances test, as in Neiman-Marcus Group and Dean.10 3 However, those cases only asked whether judicial recusal or disqualification was warranted, and did not consider whether the attorneys' actions merited sanctions or other punishment. In policing attorney contributions, state bar organizations should look at factors such as the amount, timing, and pattern of support to determine whether an attorney's actions were proper." °4 Large, frequent contributions given close in time to when an attorney's case is heard, combined with a suspicious pattern of support, should create a rebuttable presumption that the contributions were made for illegitimate reasons.' 0 5 Other factors might include "substan101 MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 3.5 (2000). 102 Goodman & Rempel, supra note 7, at 3. According to one attorney, the people making excuses like this are the only ones that benefit, and "they want it to stay that way." Id. 103 See discussion supra Parts III.B and III.C, respectively. 104 Grannis, supra note 7, at 403 (arguing that the amount and its importance to the judge, rather than its importance to the contributor, are the most important factors). If importance to the judge is used as the heaviest factor, it will overshadow any attempt by the attorney to "influence the judge," in violation of Model Rule 3.5, even if the amount is too small to actually influence the judge. Id. 105 For example, in the infamous Pennzoil case, two days after filing the answer in the case, Pennzoil's lawyer made a $10,000 contribution to the pre-trial judge, and another $10,000 contribution to the judge who assigned trial judges. See Texaco, Inc. v. Pennzoil Co., 729 S.W. 2d 768 (Tex. Civ. App. 1987). The lawyer also happened to serve on the judge's steering committee and was a liberal Democrat, while the judge was a conservative Republican. Id. The case resulted in a $10.53 billion award to Pennzoil. See Grannis, supra note 7, at 404-05; Siciliano, supra note 7, at 228-29. On appeal, representatives at Texaco contributed a total of $72,700 to seven justices and Pennzoil countered by contributing more than $315,000. See Grannis, supra note 7, at 404-05; Siciliano, supra note 7, at 228-29. Three of the justices were not even up for reelection, drawing the motives of the parties even further into question. See Alfini & Brooks, supra note 34, at 671. Although the Texas Supreme Court held that the circumstances in this case did not create an appearance of impropriety, a tougher standard would prevent such large donations in very suspicious circumstances. Id. In 1999, the ABA TASK FORCE REPORT suggested adding a provision requiring a specific contribution limit for each individual, PAC, firm, or political party. Id. The limits would be set by each jurisdiction and disqualification would be required when a judge received more than the prescribed amount; however, no states have adopted the provision. See Sample & Pozen, supra 362 CARDOZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J [Vol. 8:341 tial contributions" made to judges "running unopposed," who are "certain winners" or "certain losers," and contributions "sent to both sides in a race, or to the winner after the election."' 1 6 Attorneys should be held more accountable and be required to explain unusual campaign contributions-a small price to pay in the interest of preserving a fair and just judiciary. C. Amend Model Rule 7.6 to encompass otherforms of 'pay to play" besides judicial appointments, and close the "uncompensated 07 services" loophole' As the Comment to Rule 7.6 points out, when a lawyer makes a contribution only in hopes of receiving a judicial appointment, "the public may legitimately question whether the [appointed] lawyers . . . are selected on the basis of competence and merit."' 1 8 Similarly, when a lawyer makes a contribution only in hopes of receiving something else from a judge (e.g., more lenient treatment in cases, "favorable court note 2, at 4 (discussing how extremely difficult it is to disqualify a judge on the basis of a campaign contribution from a party or a party's lawyer, or on the basis that a judge has expressed a position on an issue that comes up in a later case). Prior to 1999, Alabama already had a similar provision in place; however, it seems that courts refused to apply the statute. See generally Val Walton, Suit Claims Governor, AG Not Enforcing Campaign Law, BIRMINGHAM NEws, Aug. 2, 2006, at 2B; Brackin v. Trimmier Law Firm, 897 So. 2d 207, 230-34 (Ala. 2004) (Brown, J., statement of nonrecusal) (asserting that he is unsure whether the recusal statute is enforceable). A few other states have related campaign guidelines in place. In New York, candidates should not knowingly accept contributions from lawyers who have cases before the candidate, nor should lawyers attempt to make such contributions. Sample & Pozen, supra note 2 at 4. Moreover, a campaign committee should not accept a single source donation that "is so large as to foster an appearance of impropriety." N.Y. State Bar Ass'n Comm. on Prof I Ethics, Op. 289 (1973). In Michigan, the rules go even further, prohibiting the solicitation of donations over $100 per lawyer; however, if a general solicitation is sent out that is not targeted specifically at lawyers, more than $100 may be solicited, so long as a disclaimer appears on the solicitation request stating that lawyers should regard the mailing as "informative and not solicitation for more than $100." MICHIGAN CODE OF JUDICIAL CONDUCT Canon 7B(2)(c) (2000). Siciliano, supra note 7, at 227; see also Grannis, supra note 7, at 408; Goodman & Rempel, supra note 7, at 2. According to a study conducted by the Los Angeles Times, a state judge running unopposed in an election collected $80,000 in campaign funds. Goodman & Rempel, supra note 7 at 2. Of the fifty-four contributors who gave more than $500, fifty-one of them had cases pending before the judge or assigned to her courtroom. Id. On the night before one big fundraiser, four law firms with cases pending before the judge gave her twelve bottles of wine, a television, two DVD players, a gas grill, dinner for four, two theater tickets, two golf lessons, and a pool float with two beach towels. Id. 107 See discussion supra Part II.E. 108 MODEL RULES OF PROF'L CONDUCT R. 7.6 cmt. n. 1 (2000). 106 2010] JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA 363 dates on crowded dockets,"' °9 a better chance of expediting cases or getting extensions), "the integrity of the profession is undermined."'110 As previously discussed, the "uncompensated services" loophole in Rule 7.6's definition of "campaign contribution" should be closed.' It is counterintuitive that uncompensated services are not considered campaign contributions for the purposes of determining whether or not an attorney can donate services in hopes of receiving judicial appointments. If volunteering for a judge's election committee or campaigning for a judge is done "for the purpose of' obtaining judicial appointments, these services should also be prohibited under Rule 7.6. D. Change the standardunder Rule 3.5(a) to a reasonable person standard Currently, the language of Rule 3.5(a) prohibits a lawyer from "seek[ing] to influence a judge" by improper means. In order to show that this rule has been broken, proof must be given to show that a lawyer actually sought to improperly influence a tribunal. In Bolton, the majority determined that this could not be proven, and therefore Bolton walked away with a comparatively light reprimand after outright offering a judge $5,000. If the Rule also captured behavior that appears to a reasonable person to seek improper influence of a tribunal, attorneys would be forced to be more vigilant in their interactions with tribunals generally, and individual judges specifically. If a reasonable person would not find the behavior to be directed at improperly influencing a judge, then the acting attorney has nothing to worry about. E. Strengthen judicial disqualification requirements when a judge receives contributionsfrom attorneys who (1) contribute during the pendency of a case; (2) have served actively on the judge's campaign committee; or (3) ran as the judge's defeated opponent in the election Using the factors suggested above to analyze the legitimacy of an attorney's campaign contribution, when one party contributes a dispro109 Goodman & Rempel, supra note 7, at 4. 110 Id. For example, a judge in Las Vegas signed twenty-nine orders temporarily returning driving privileges to one attorney's clients, even though the clients' drunk-driving cases were being heard by other judges. See Michael J. Goodman & William C. Rempel, Special Treatment Keeps Them Under The Radar, L.A. TiMes, June 10, 2006 (Saturday Home Ed.), at Al. The judge also granted 86% of DMV hearing appeals in favor of the attorney's clients, while such appeals are normally rejected more than 90% of the time. Id. "I See discussion supra Part II.E. 364 CARDOZO PUB. LAW, POLICY & ETHICS J [Vol. 8:341 portionately large amount of money to a judge assigned to a pending case and the other party files a motion to disqualify the judge, the case should be reassigned. This type of rule would require disqualification in infamous cases such as Texaco, Inc. v. Pennzoil Co. 1"2 and Avery v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 113 as well as instances like the fundraiser for Judge Porter described in the Introduction." 4 In addition, following Neiman-Marcus Group, judges should be disqualified from cases being argued by an attorney who has served actively on the judge's campaign committee, including service as chairman, secretary or treasurer.' 15 Lastly, if a losing party to the judge's election is assigned to come before the judge, the judge should be disqualified in order to dispel any questions of the judge's ability to remain impartial." 6 112 See supra note 105, discussing Texaco, Inc. v. Pennzoil Co., 729 S.W. 2d 768 (Tex. Civ. App. 1987). 113 Avery v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 835 N.E.2d 801 (Ill. 2005). In Avery, a state court circuit judge running for a seat on the state supreme court received $1 million in contributions from individuals or groups affiliated with a party who had a breach of contract case pending before the state supreme court during the election cycle. Id. The justice admitted that the fundraising was "obscene," but stayed on the case and ultimately cast the deciding vote in the breach of contract case, overturning a $456 million verdict. Id; see also Ryan Keith, Spendingfor Supreme Court Seat Renews Cry for Finance Reform, Assoc. PREss, Nov. 3, 2004, at 1. 114 See also Siciliano, supra note 7, at 238. "If the campaign is active at the time of the appearance [of the contributing party], the judge should automatically be disqualified from hearing the case, the appearance of impropriety being too great to dispel." Id. Besides the extreme examples previously cited, other questionable cases could also be averted by this rule. See J-IV Invs. v. David Lynn Mach., Inc., 784 S.W.2d 106, 108 (Tex. Civ. App. 1990) (defense counsel made a contribution to the judge while he was considering a motion to set aside the jury verdict and the judge later granted the motion). Although New York already has a similar rule, see Alfini & Brooks, supra note 34, at 709 (citing N.Y. State Bar Ass'n Comm. on Prof I Ethics, Op. 289 (1973)), other states maintain that recusal is unnecessary in similar situations. See STANDING COMMITTEE ON JUDICIAL ETHics & ELECTION PRAcTIcEs, Propriety of Judicial Recusal Where Attorney Has Contributed to Judge's Election Campaign, 10 Nevada Lawyer 23 (Mar. 14, 2002) (citing City of Las Vegas Downtown Redevelopment Agency v. District Court, 116 Nev. 640 (Nev. 2000)). 115 Similar suggestions have previously been made. See, e.g., Siciliano, supra note 7, at 22324; Alfini & Brooks, supra note 34, at 702. 116 This was previously suggested by the Florida Ethics Commission. See Fla. Sup. Ct. Comm'n on Standards of Conduct Governing Judges, Op. 84-23 (1984). 2010] JUDICIAL ELECTIONS & COURTROOM PAYOLA 365 F. Make judicial recusal a feasible option when no rules have been broken per se, but "impartialitymay reasonably be questioned"' 17 Ideally, implementing the above recommendations would curtail inappropriate attorney judicial campaign contributions, making recusal less necessary. However, in those cases where improper behavior cannot be proven, but the question of impartiality reasonably remains, recusal motions should be made a viable option for affected parties. According to research done by the Brennan Center, in most courts, judicial recusal practices are not rigorous and may even be "systematically underused and underenforced."' 1 8 If litigants fear bringing valid recusal motions because they may anger judges,' and because the odds of success are extremely low, recusal is currently an illusory tool in maintaining judicial impartiality. 1 9 Various proposals have been made to strengthen recusal, 120 and while the specific pros and cons of each are outside the scope of this Paper, any plan to mitigate inappropriate attorney campaign contributions should not ignore the important role recusal may play in improving and preserving justice. CONCLUSION It is clear from the examples discussed in this Paper that attorneys frequently contribute to judicial campaigns with improper motives attached. It is also clear that the current Model Rules and their enforcement are weak when it comes to addressing, punishing, and correcting attorney behavior. The author recommends adopting some or all of the above proposals as a positive step toward restoring integrity to the process of attorney campaign contributions in judicial elections. 117 The current version of CJC Canon 3E(1), calling for disqualification when "impartiality might reasonably be questioned," arguably sets forth a very broad standard for when disqualification may be appropriate. See Sample & Pozen, supra note 2, at 3. 118 Id. (discussing Justice Kennedy's suggestion that states may want to adopt "recusal standards more rigorous than [constitutional] due process requires"). 119 Likely contributing to the low success rate is the fact that a judge granting a recusal motion would be impliedly stating that she failed in the first instance to recuse herself sua sponte, as required by Canon 3E(1). See id. 120 The ABA TASK FoRCE REPORT suggested requiring full disclosure of lawyer contributions, and this was "[t]he one area of campaign finance regulation that has been the most widely supported." See SCHOTLAND INTERVIEW, supra note 17 at 15, 18 (discussing ABA recommendations). California already has a similar provision requiring disclosure, "even if the judge believes there is no actual basis for disqualification." See Sample & Pozen, supra note 2, at 5; see also Siciliano, supra note 7, at 237 (stating that the judge should always be required to make a disclosure if one of the parties has contributed, and if the judge is unaware, the burden should fall on the contributing attorney).