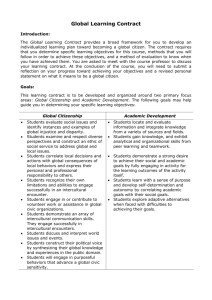

Worldly Citizens: Anti-Patriotism as a Civic Virtue

advertisement

Worldly Citizens: Civic Virtue without Patriotism Simon Keller, Victoria University of Wellington 1. From civic virtue to patriotism There can be no state without citizens, and no flourishing state without good citizens. A healthy democratic state is sustained by citizens who, among other things, follow the law, pay their taxes, contribute to the state‟s political life, work to make the state more just, and are prepared to protect the state against other states, should the need arise. 1 A civic virtue is a character trait that helps make a person a good citizen. According to a natural and common line of thought, one civic virtue – and hence one character trait a state has reason to commend and cultivate – is patriotism. 2 And the reason why patriotism is so naturally regarded as a civic virtue is that it seems so obviously better than the alternatives. For many authors and many politicians, the pertinent alternative to patriotism is selfishness. 3 People who do not have patriotic attachments to their countries, it is assumed, are unlikely to be attached to anything much, apart from themselves. Someone who cares only about himself will not be a good citizen, because he will not make sacrifices for his country or his compatriots. The remedy to selfishness, on this 1 For a helpful taxonomy of the roles of the good citizen, see p. 631 of William A. Galston, „Pluralism and Civic Virtue,‟ Social Theory and Practice 33:4 (2007): 625635. 2 The basic case for considering patriotism a civic virtue is nicely laid out (though not endorsed) by Harry Brighouse in ch. 6 of his On Education (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2006), see especially p. 102. 3 For a philosopher‟s view, see Andrew Oldenquist, „Loyalties,‟ Journal of Philosophy 79 (1982): 173-193, especially pp. 187-191. For a politician‟s view, see John McCain‟s article in Time magazine (25 June 2008). McCain, writing as the Republican nominee for US president, says that patriotism is “service to a cause greater than self-interest,” and draws a contrast between the “good citizen and patriot,” on the one hand, and the “cynical and indifferent” person, on the other. 1 way of thinking, is the cultivation of loyalty to country. Someone who acts for her country, not just for herself, is more likely to act as a good citizen. For others, especially in the academic literature, the interesting alternative to patriotism is not selfishness but cosmopolitanism. 4 The cosmopolitan‟s first commitment is to humanity undifferentiated. The cosmopolitan sees himself as a citizen of the world. While the cosmopolitan may show great concern for others, runs the thought, he does not show any special concern for his own country and its people. The cosmopolitan, it appears, will then have no motivation to promote the flourishing of this country, rather than others: no motivation to promote justice here rather than elsewhere, no motivation to protect this country rather than its neighbors.5 When the comparison is with cosmopolitanism, patriotism becomes the cause of particularity. The patriot, in contrast with the cosmopolitan, has the motivation required to be a good citizen of her own country in particular. The claim that patriotism is a civic virtue plays a special role in the prevailing debate about the ethics of patriotism. Many arguments against patriotism depend upon evaluations of patriotism as a narrow personal trait. It is argued that patriotism involves the drawing of morally obnoxious boundaries of concern, that patriotism is a kind of idolatry or self-abasement, and that patriotism encourages self-deception. 6 4 See, for example, Alasdair MacIntyre, „Is Patriotism a Virtue?‟ The E. H. Lindley Lecture, University of Kansas, 1984. Reprinted in Patriotism, ed. Igor Primoratz (Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2002), pp. 43-58 (see especially pp. 48-50). See also the debates in Martha C. Nussbaum and Joshua Cohen, For Love of Country? (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002); and Stephen Nathanson, „Is Cosmopolitan Anti-Patriotism a Virtue?‟ in Patriotism: Philosophical and Political Perspectives, eds. Igor Primoratz and Aleksander Pavkovic (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), pp. 75-91. 5 See Anna Stilz‟s case of Sally from Toronto, in Stilz, Liberal Loyalty: Freedom, Obligation, and the State (Princeton University Press, 2009), pp. 3-9. 6 Paul Gomberg, „Patriotism Is Like Racism,‟ Ethics 101 (1990): 144-150; Nussbaum, „Patriotism and Cosmopolitanism,‟ in For Love of Country? pp. 3-17; George Kateb, „Is Patriotism a Mistake?‟ Social Research 67:4 (2000): 901-924; Simon Keller, „Patriotism as Bad Faith,‟ Ethics 115:3 (2005): 563-592. 2 Against such arguments, the link between patriotism and good citizenship can be played as a trump card. Whatever the drawbacks of patriotism viewed in isolation, it may be said, from the point of view of the political community we cannot do without it. Putting it another way: even if we concede that patriotism is distasteful intrinsically, we can say that its instrumental value, through its connection with good citizenship, is so great as to make it a good thing, all things considered.7 My goal in this paper is to interrupt the argument from the value of good citizenship to the importance of patriotism, by drawing attention to a third alternative to patriotism. There are many people who move from one country to another, and who become perfectly good citizens of their new countries, without ever becoming patriots of their new countries. These people are not purely selfish, and they need not be cosmopolitans. They are, I shall say, “worldly citizens,” and their ways of thinking about and engaging with their adopted countries provide a model of good nonpatriotic citizenship that anyone, in principle, can follow. When patriotism is compared with worldly citizenship, not just with selfishness and cosmopolitanism, patriotism looks less appealing. Before getting to worldly citizenship, I need to do a little by way of setting up the argument. First, I will say something about the nature of patriotism, and about patriotic citizenship. That in hand, I will say how my question relates to two other debates in the vicinity, which have recently gained a great deal of attention: the debate about liberal nationalism, and the debate about special duties to compatriots. Then, I shall give my description of worldly citizenship and its virtues, explaining why I think that worldly citizenship is as good as – and in some ways better than – patriotic 7 Galston, „Pluralism and Civic Virtue,‟ 625-627; Eamonn Callan, „Love, Idolatry, and Patriotism,‟ Social Theory and Practice 32:4 (2006): 525-546, p. 526; Sigal BenPorath, „Civic virtue out of necessity: Patriotism and democratic education,‟ Theory and Research in Education 5:1 (2007): 41-59, p. 49. 3 citizenship. Finally, I shall offer some thoughts about the link between worldly citizenship and cosmopolitanism. 2. Patriotism Patriotism is loyalty to country. But not just anything counts as a country, in the respect necessary for patriotism, and not just any loyalty to country counts as patriotism. Here are some of the conditions that loyalty to country must meet, if it is to qualify as patriotism. First, the object of love – the country – must be politically unified and independent, or must be an entity that the patriot wishes to be politically unified and independent. You can be a patriot of America, but you cannot be a patriot of New York, or of New England, or of greater North America, unless it is your aspiration that New York or New England breaks away from America and achieves statehood for itself, or that the countries of greater North America unite and form a single state. Similarly, if it is your wish that America be absorbed into a greater North American state, then you are not a patriot of America. As it is often put in the literature, to be a patriot is to be committed to your country conceived as a project, where the project in question involves the flourishing of the country as a distinct political entity. 8 Second, the country to which you are loyal must be your country, in quite a demanding sense.9 If you are an American, then you might love France, and you might even feel a kind of loyalty to France, but you cannot be a patriot of France, 8 MacIntyre, „Is Patriotism a Virtue?‟ pp. 52-53; Callan, „Love, Idolatry, and Patriotism,‟ pp. 534-535; Igor Primoratz, „Patriotism – Morally Allowed, Required, or Valuable?‟ in Primoratz (ed.) Pariotism, pp. 187-199, see pp. 188-189; Margaret Moore, „Is Patriotism an Associative Duty?‟ The Journal of Ethics 13:4 (2009): 383399, see p. 385. 9 MacIntyre, „Is Patriotism a Virtue?‟ p. 44; Callan, „Love, Idolatry, and Patriotism,‟ p. 533. 4 because France is not yours. Nor can you simply decide to make France your country, in the sense that would allow you to become a French patriot. In standard cases, at least, you can no more decide which is to be your country than you can decide who is to be your mother. If you move from America to France, you may become a citizen of France, and you may make France your home, but that does not necessarily make you French – not in the sense required for French patriotism. Third, as a patriot your loyalty to country is, as we might say, basic. It is not derived from any deeper commitment, or inculcated explicitly to serve some independent purpose. Your attachment to America might be dependent upon your commitment to democracy, so that you support America for just so long as supporting America is a good way to further the cause of democracy; then, your attachment to America is not the attachment of a patriot. You might be loyal to America just because you think that being loyal to America is fun, so that the minute it ceases to be fun, you would see no reason for your loyalty to survive; then, again, you are not a patriotic American. If you are patriotic American, then you are loyal to America in the first instance, as you might be loyal to your child or your parent in the first instance – not, that is, because America meets some independently specified value or role. 10 Fourth, and related to the last two points, the loyalty of a patriot is a kind of expression of identity. To be an American patriot, you must be American, but you must also take it to matter – to be an important fact about who you are – that you are American. To some extent, your conception of yourself must be tied in with your conception of your country. You cannot be a patriot, while at the same time thinking that what happens to your country happens simply to other people, or that whether 10 MacIntyre, „Is Patriotism a Virtue?‟ p. 44. 5 your country succeeds or fails means nothing for your life. To this extent, insofar as you are patriotic, you take the fate of your country personally. 11 Those, anyway, are four features of patriotism. None of them is supposed to be a point of controversy. Among writers who take themselves to be talking about “patriotism” in its ordinary sense, at least, the four features are widely accepted as essential elements of patriotism. There are other aspects of patriotism apart from these, but these are four that I take to be uncontested, and to play the most important roles in allowing us to understand patriotic citizenship. 12 There is no guarantee that a patriot will be a good citizen. A patriot could have a nasty, exclusionist conception of her country‟s national project; she could have a hatred for those whom she thinks fail to live up to the country‟s values; she could be weak-willed or easily manipulated; she could be wrong about what it takes for her country to flourish. But, it is easy to see how someone who is a patriot, displaying the four features of patriotism just mentioned, could thereby be likely to be a good citizen. If a patriot lives in her own country, then the country to whose laws she is subject, to which she owes taxes, and so on, will be a country in whose flourishing she takes a deep and personal interest. She will not relate to the country simply as one individual to an impersonal institution, or to the country‟s other inhabitants simply as one individual to other individuals. It will matter to her, for its own sake, that her country and its inhabitants do well. She will have a motive to make sacrifices for the sake of her country‟s flourishing, whether that means working to make her country more just, or, at the extreme, defending her country on the battlefield. Her commitment to her country will not be conditional, in any straightforward respect. 11 Igor Primoratz, „Patriotism: Mapping the Terrain,‟ Journal of Moral Philosophy 5 (2008): 204-226, see pp. 223-224. 12 I give a more complete characterization of patriotism in ch. 3 of my The Limits of Loyalty (Cambridge University Press, 2007). 6 She will not see the country simply as a vehicle for her independent goals or values. She will have a special focus upon serving and improving her country in particular. Accordingly, there are reasons to think the patriot ideally placed to perform as a good citizen. 3. Liberal nationalism and special obligations It may be helpful to locate the debate about patriotism and citizenship with respect to two other debates about citizenship that have recently received a great deal of attention. Some prominent political philosophers argue for a view called “liberal nationalism.” They say that liberal principles can (or must) be manifested within a political community made up of individuals united by bonds of shared ethnicity, or shared religion, or shared history (real or imagined), or a shared and distinctive way of life: a community that constitutes a nation, not just a polity. 13 The demand for liberal nationalism, for present purposes, can be seen as one that incorporates and then goes beyond the demand for patriotic citizenship. The allegiance to nation recommended by liberal nationalists is similar to the allegiance to country displayed by a patriot, with the added condition that the cause of the country should coincide with the cause of a nation. The question of the connection between patriotism and nationalism (and liberalism) is complicated, but what matters for now is that when I advocate an alternative to patriotic citizenship, I take myself thereby to advocate an alternative to liberal nationalism too. The debate about patriotism, along with the debate about nationalism, concerns motivation; it concerns patterns of emotion, loyalty, identity, and concern. 13 The major defenses of liberal nationalism are Yael Tamir, Liberal Nationalism (Princeton University Press, 1993); and David Miller, On Nationality (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995). For critical discussion, see Stilz, Liberal Loyalty, especially ch. 6. 7 Another question about our relationships with our countries, which more narrowly concerns action, is whether we have special obligations to our countries and compatriots. Some political philosophers argue that we can derive such special obligations from an impartial or liberal starting point, properly construed. The claim is that purely impartial or liberal principles can show why we should pay taxes to our own countries but not other countries, work to promote justice in our own countries before other countries, and so on.14 Strictly speaking, this claim is independent of the question about patriotism, because it is possible to recognize and fulfill special obligations to your country or your compatriots without feeling any patriotic sentiment towards them. Having taken a loan from a bank, you could see that you have an obligation to repay the loan, rather than spending your money on other things, and thereby be motivated to meet your obligation to the bank, even without feeling any loyalty to your bank, even while despising it. In the same way, you might see that your first obligation is to your country, while wishing it was not – and hence while failing to be patriotic. 4. Worldly citizens There are some people who do not have countries of their own, and there are some people who have countries of their own but do not live in them. I am not thinking only of people who are stateless or exiled, but also of people who choose to move, for whatever reason, from one country to another. 14 See, for example, Robert E. Goodin, „What is So Special about Our Fellow Countrymen?‟ Ethics 98:4 (1988): 663-686. Anna Stilz‟s recent Liberal Loyalty argues that citizens have an obligation to participate with their compatriots in certain activities of collective agency, required in order for the liberal state to exist and to flourish. While Stilz presents her argument as a defense of “loyalty,” it is really about special obligation. The book contains no suggestion that citizens should fulfill their obligations out of loyalty to country, rather than out of some other motivation. See Stilz‟s definition of “loyalty” on p. vii, and the discussions on p. 172 and in ch. 7. 8 Think of a person who moves successively from country to country during her childhood. She might be born in Oklahoma City but move with her family to Geneva before she turns three; then she might live for a few years at a time in Hong Kong, Cape Town, and Paris, before finally taking a job in Reading and, eventually, becoming a British citizen. If we ask her, “Which country is yours?” she might honestly say, “No country, really. I was born in America, but I am not really an American. Geneva, Hong Kong, Cape Town, and Paris all feel, in their own ways, like home, but I could never claim to be Swiss, or Chinese, or South African, or French. And while I am happy living in Reading, I come to Britain as an outsider. I do not have one country that I can consider, above all others, to be mine.” Someone who grows up in Australia, then moves to America to study and decides to stay, may continue to identify himself as an Australian, even while taking up American citizenship, and even while fully embracing his new life in America. Someone who immigrates to New Zealand from India, and starts a family in his adopted country, may honestly say, “I will never again live in India; my home is now in New Zealand. But, while my children are New Zealanders, I will always be Indian.” It is not possible for people like these to be patriotic citizens. The countries to whose laws they are subject, to whom they pay taxes, and in which they vote, are not their countries, in the sense that matters for patriotism. The Australian who moves to America may never be able to classify himself as an American, still less an American patriot – even, again, if he becomes formally an American citizen. Even as an American citizen, making a life in America, his patriotic feelings, if any, may be directed still at Australia. Yet, it is obviously possible for people like these to be good citizens. An immigrant to a new country can follow the country‟s laws and pay her taxes; she can 9 volunteer to help the vulnerable; she can work as an activist; she can take up political causes; and she can join a political party, stand for office, and strive to achieve justice within her new country. Immigrants often conduct themselves as perfectly good citizens, even when they do not have access to patriotic motivation. The good citizenship of immigrants shows that good non-patriotic citizenship is not only possible, but common. Sometimes, an immigrant‟s motivation for acting as a good citizen will be, even if not genuinely patriotic, pseudo-patriotic. The Indian who moves to New Zealand may not become a New Zealand patriot, but he may learn to think like a New Zealand patriot. In his civic activity within New Zealand, think and behave as if he were a patriotic New Zealander. If that is the characteristic attitude of good citizens of adopted countries, then it does not stand as an interesting alternative to patriotic citizenship. But there is another attitude, quite different from the attitudes of the patriot and the pseudo-patriot, which is commonly found among good citizens of adopted countries, and that involves a much more complex pattern of commitments. An immigrant to a new country is likely to form her first attachments not to the new country itself, but to the particular places and communities within which she makes her new life. If the Australian immigrant makes his home in New York, for example, then he may well form an attachment to New York, and come to identify as a New York local, indeed as a New Yorker, without ever coming to identify as an American. He may well feel that he is at home in New York, and that he has a bond with other people from New York, without having any sense that his home also takes in Dallas, or the Mid-West, or California, just because those places, like New York, are in America. That he comes to experience New York as a local will not at all prevent him from experiencing other parts of America as a foreigner. 10 Similarly, the person who lives successively in Oklahoma City, Geneva, Hong Kong, Cape Town, Paris, and Reading may feel attached to each of these places, without feeling any independent attachment to America, Switzerland, China, South Africa, France, or Britain. She may feel that she is coming home when she visits Paris, without feeling that she is coming home every time she enters France. Speaking generally, it is common that the immigrant‟s sense of place, and of identification with particular communities and ways of life, settles not on the new country, but on the particular parts or aspects of the new country with which she becomes familiar. A first crucial difference between the patriotic citizen and the immigrant citizen, as described, is that where the patriot‟s basic attachment is to the country itself, the immigrant‟s basic attachments are to places and communities within the country. When someone lives in many countries successively, or grows up in one country and moves to another, she may yet have a strong sense of place, and a strong sense of which places do and not feel like home. It is just that “home,” for her, is not coextensive with a single country. A further difference between the patriotic citizen and the immigrant citizen is that the immigrant is much more likely to understand the country as one among many. As someone who has lived in another country, and whose first experience of the new country is as an outsider, the immigrant will place the new country in a more worldly context, seeing its political arrangements, its way of life, and so on, as one way things could be, but not as a way things can normally be assumed to be. The immigrant citizen will always have an awareness of how her adopted country is distinct and how it is idiosyncratic. The patriot is likely to see the world from within the perspective of her own country. The immigrant, even as she forms attachments to parts and aspects of the country, is likely also to know how it looks from outside. 11 The kind of citizen I have tried to identify is not a world citizen, but is also not a patriot. She is, I want to say, a “worldly citizen”: genuinely a citizen of a particular country, and with particular attachments to places and communities within that country, but taking upon her country a perspective informed by her knowledge that that country is not the only one there is. The immigrant citizen may be a good citizen of her adopted country. Worldly citizenship can, in principle, be good citizenship. But can it be as good as patriotic citizenship? Looking at the differences between worldly and patriotic citizenship, is there a reason to prefer one to the other? 5. Civic motivation One way to assess a person in her role as citizen is to ask how she is motivated and what she is prepared to do. Citizens are called upon to perform tasks and make sacrifices for the good of the community. A good citizen follows the law and pays her taxes, even when it does not serve her interests. She plays her part in civic life, which could involve volunteering, running for office, or working as an activist. Under extreme circumstances, the mark of a good citizen is the willingness to risk her life and fight for her country. To some extent, being a good citizen is just a matter of caring for those around you. To that extent, there is no reason to think that the patriotic citizen or the worldly citizen will be a better citizen than the other. The Indian who has moved to New Zealand is not any less likely than a homegrown New Zealander to have a concern for the vulnerable, to give to charity and volunteer for good causes, to be a parents‟ representative in the management committee of the local school, or, generally, to be willing to put in an effort to help other people in his community. When it comes to 12 other elements of good citizenship, however, patriotic citizenship may appear to hold an advantage. The country is the direct object of a basic loyalty of the patriotic citizen, and it takes a central place in her self-conception. That some act would advance the flourishing of her country will always, for the patriot, be a reason to perform it. It will be possible for the patriot to be moved by the simple thought of doing something for her country: the thought of acting “for America” or “for France.” In contrast, the country itself will not play a basic motivational role in the thinking of the worldly citizen. The Australian living in America, for example, will not think of himself centrally as American, and will not be moved to do something just “for America.” Yet, the worldly citizen can still do things that promote the flourishing of the country, and can still find reason to care about the country, even if her motivation must be indirect. If the immigrant to America has become a local of New York, then he will be moved to do things that are good for his city and for communities and institutions within the city. He might, for example, want to support an art gallery, or the arts generally, in the part of New York in which he lives, and that may move him to take an interest in the acts and policies of the American government as they relate to the arts. He may also have certain commitments of principle that lead him to get involved in local and wider political causes. He might be a libertarian or a socialist; he might care about animal welfare or capital punishment; he might want to protect wilderness areas or help underprivileged children get better access to education. As a person who lives in America and has particularized attachments to things within America, as well holding general politically salient values and principles, he can find many reasons to 13 do things that are good for America, and indeed to care about America as a political entity and to want America to do well. The worldly citizen‟s concern for her country will be derived from other attachments and commitments, but that does not mean that her concern for her country will be slight or unreliable. Two crucial points are easily overlooked. First, the role played by a country and its policies is, for those within the country, farreaching and all-encompassing. Any concerned citizen who has decided to live permanently in a country, and who has formed attachments and taken on causes within that country, will have a reason to want the country to flourish politically, even if her concern for the country is derived, not basic. Second, and most importantly, the structure of a commitment is not a measure of its strength. A commitment can be basic, yet weak. Your concern for the fortunes of your favorite football team may be basic – not derived from any deeper commitments – but you might nonetheless be only a mildly enthusiastic fan, and not care about your football team very much. Conversely, a commitment can be derived, yet very strong. You may have no basic loyalty to your local school, but you might put a great deal of effort into improving the school, and you might be prepared to fight furiously for its existence if it comes under threat, because you care about education and you care about your neighborhood, and because it is the school your children attend. Your commitment to the school may be derived from your more general commitments and your commitment to your own children, but that does not prevent your commitment to the school from being very strong. I suspect that the conflation of the structure with the strength of political commitments is a mistake embedded in a great deal of thinking about patriotism and nationalism. Political philosophers often seem to assume that if we are to have 14 citizens with strong commitments to the state, then we must have people with basic commitments to the state. But a person can care deeply about the state, not for its own sake but for its vital connection with the causes to which she has more fundamental commitments. Consider the kinds of motivations that a soldier might have in marching off to war under the flag of his country. He might be moved by thoughts of his country; he might be prepared to die “for France” or “for America.” Or, he might be moved by thoughts of smaller things within his country; he might be prepared to die in defense of his family and his city and the life he loves. Or, he might fight for principles; he might be prepared to die for freedom or democracy or the fight against fascism. The first of these is the distinctive motive of the patriot, but the others make perfect sense, and can be very powerful. You do not need to be patriot to be prepared to make even the most significant of sacrifices in defense of a county. 6. Civic judgment It is one thing to be motivated to help your country flourish, and another to make the judgments and choices that actually help your country flourish. Part of what it is to be a good citizen is to make considered, judicious, community-minded decisions about such questions as how to vote, which policies to support, when to disobey a law, and when and how to exert influence on elected representatives. A person who cares greatly about the health of his country, but who suffers from misinformation or exhibits completely misguided values, will not act as a citizen should. So another way to assess a person in her role as citizen is to ask about the quality of her judgment, as it relates to her performance in that role. 15 To exercise good civic judgment, a citizen must be informed about the state of her country, and about what actions and policies will have what outcomes. She must also have right-minded values, so that the actions she performs and policies she supports are those that will indeed make her country better. On both scores, the civic judgment of a person will be of greater quality if she has an understanding of what is special about her country. Good civic judgment arises partially from an appreciation of the values and ways of life by which a country is characterized. A worldly citizen has local knowledge and an appreciation of local values. The judgments of the worldly citizen will be informed by a desire to protect what is good in what she finds around her. The immigrant to America who lives in New York can make judgments as a New Yorker, even if not as an American; the immigrant to New Zealand can take a political interest arising from his intimate acquaintance with certain places and communities within New Zealand. In that respect, the judgments of the worldly citizen are similar to the judgments of the patriotic citizen. In other respects, they are likely to be better. First, the worldly citizen, who understands the country as one among many, will be better able to see what is good and bad about the country, and where that places the country in relation to the rest of the world. She is less likely than the patriot to want to classify all values she finds around her as “American values,” for example, and hence more likely to see how far those values really extend, within and outside the country, where they really come from, and to what changes they are susceptible. To that extent, the worldly citizen is likely to make superior judgments about what should be changed about the country and how change could be achieved. Second, the worldly citizen will not face a temptation to oversimplify her country, or to overreach in her judgments about what her country is and how it should 16 be. A patriot requires a conception of her country as a basic object of loyalty; she needs to have a picture of the thing about which she has a fundamental concern. People really, however, are immediately acquainted with only some aspects of their own countries. Most of us have no intimate knowledge of the lives of most of our compatriots. An American who grows up in New York should not presume to have any special inside knowledge of life in rural Arkansas, just because Arkansas is in America, any more than should the person who moves to New York from Australia. But the patriot needs – or will at least be tempted – to make judgments on the basis of generalizations about her country, because she needs to represent her country to herself as a country distinct from others, set apart by certain specified characteristics and values, so that it can then be the focus of a non-derived loyalty. That is a kind of distortion of judgment to which the worldly citizen, who need make no pretense to knowing about a whole country, need not be subject. Third, the worldly citizen‟s civic judgment will not be entwined with her view of herself. Patriotic identification with country is often of a kind that produces pride or shame; the patriot‟s esteem for his country is related to his self-esteem. As a result, the patriot is likely to hold on to a particular picture of his country, and to feel that if that picture is under attack then he is under attack too. When your self-esteem is invested in something, it is often more difficult to see that thing as it really is. Compared to the patriot, the worldly citizen has one fewer obstacle to taking a cleareyed view of her country – of how her country is and of how it could change – and hence one more advantage over the patriot when it comes to making judgments that will help the country improve and flourish. 15 15 See Amy Gutmann, „Civic Minimalism, Cosmopolitanism, and Patriotism: Where does Democratic Education Stand in Relation to Each?‟ in Stephen Macedo and Yael Tamir (eds.) Moral and Political Education (New York University Press, 2002) pp. 17 Consider again the person who lives in several countries, then settles in Reading. Imagine that during her time in Reading, Britain faces a referendum on whether or not it should become a republic. For any British citizen, the decision raises questions about how Britain would be different if it were no longer a monarchy, and questions about what would be the best form for any new British republic to take. The immigrant‟s experience as someone who has lived in Britain under a monarchy, and also in various other countries under other political systems, will enable her to reach especially well informed answers to these questions. She is likely to have a relatively clear-eyed view of what would happen to Britain as a result of any given change to its present system of government. In deciding how to vote in the referendum, she will be informed by an understanding of the community and culture she finds around her, without imagining that what she knows about Britain is representative of Britain as a whole. For a British patriot, the question of whether Britain should become a republic is likely to raise further, more personal issues. The patriot is likely to worry about how “Britishness” would fare, if the monarchy were or were not overthrown, and to worry about what a change in the British state would mean for his conception of himself. He may be swayed by intimations that for Britain to become a republic would be for Britain to admit that it was wrong – and perhaps that the French were right – all along. From the other side, he may feel the force of suggestions that the British people would be growing up – and by extension, that he himself would be 23-57. Gutmann offers a view in many respects similar to mine, and to which I am indebted. She emphasizes the importance of students‟ learning about their own country by placing it in the wider world. (See especially pp. 44-53.) She says, however, that to learn about the various lifestyles and cultures within one‟s country, as distinct from those overseas, is to “learn about oneself” (p. 52). Her model of civic education then imports elements of the patriotic identification of self with country, and the accompanying distortions of civic judgment. 18 growing up – if they were to cast the monarchy aside and replace it with a republic. All of these issues are distractions. They steer the British patriot away from making a constructive and informed judgment about what is best for his country. In many ways, then, a patriotic attachment to country can be an impediment to a person‟s judgment in her role as citizen. This is one respect, then, in which the worldly citizen can be expected to be not just as good a citizen as the patriot, but better. 7. Achievability Whatever else may be true of patriotic citizenship, it is achievable. Patriotism is so common as to seem natural, and we appear to know much about how to cultivate patriotism among citizens, especially through the education system. For all the attractions of worldly citizenship, it might not look like a model of citizenship that we could hope to be widely manifested. Most citizens, after all, are not immigrants, and if worldly citizenship is only available to immigrant citizens, then it can hardly be presented as a true alternative to patriotic citizenship. A further question to ask in assessing worldly citizenship, then, is whether we could realistically hope to have worldly citizenship for all. I have introduced worldly citizenship by way of the perspective of the good immigrant citizen, but there is nothing about that perspective that makes it available only to immigrants. The perspective of the worldly citizen has three relevant features. The first is an appreciation for the local, particular places and communities with which she is immediately acquainted. The second is an understanding of and commitment to general principles of justice and compassion. The third is a sense of how her country of citizenship fits into the wider world. 19 There is nothing artificial about the first feature of worldly citizenship; it requires simply a proper appreciation for what you find around you. The second feature of worldly citizenship, involving understanding of general principles, is perhaps difficult to cultivate, but it is an essential aspect of good citizenship however understood; even a good patriotic citizen must have a sense of what makes for a just society and of how we ought to treat our fellow humans. A more significant challenge is presented by the third feature, involving knowledge of other countries and of how the citizen‟s own country might be viewed from the outside. It might be difficult to see how this aspect of worldly citizenship could be manifested in someone who has only ever lived in one place. The best response to the challenge, I think, is not to downplay the difficulty of having people learn about other countries and see how their own country looks from the outside, but rather to emphasize the artificiality of patriotic education, and by extension of the perspective of the patriotic citizen. It is easy to forget how inventive we must be in order to present a country in a manner that encourages people to identify with it, and to take it as an object of a basic loyalty. 16 It takes active intervention to cultivate patriotism. We must tell stories in particular ways; we must decide what to make part of the country‟s narrative; we must decide what are to be the country‟s defining symbols and qualities; we must encourage patriotic activities, like singing the anthem and saluting the flag. This is not just a matter of making a person recognize and embrace his own true self, but is instead a matter of having a person identify with things quite distant from his own experience. What an Australian patriot sees as “Australian” will go well beyond what he finds in his own life and what he 16 Sigal Ben-Porath‟s case for teaching patriotism in „Civic virtue out of necessity‟ rests partly on the claim that patriotism is a “moral reality” that arises whether we want it to or not; see especially p. 49. 20 finds immediately around him, and will have little to do with the lives and circumstances of many of his fellow Australians. There is nothing more natural about causing a child growing up in New York to identify with the Wild West than there is about causing him to understand how America‟s political system is like and unlike the political systems in various other countries. Having people come to see their country in a certain way is always a constructive process, never just a matter of leaving people as they are. It always requires people to be taken beyond the local and the familiar. There is a genuine choice to be made about how we encourage the citizen to imagine his country. Do we encourage the citizen to identify closely with the country, and to accept a picture of it and his relationship with it that makes him most likely to take it as an object of a basic loyalty – and thereby cultivate patriotic citizenship? Or do we encourage the citizen to understand the country as one that has a special significance for him and the things he cares about, but that is ultimately one country among many – and thereby cultivate worldly citizenship? It is possible that humans are naturally primed to be patriotic, but not to be worldly. It is possible that we will always have more success in encouraging people to be patriotic citizens than in encouraging people to be worldly citizens. But who can know? We should not imagine that the matter is settled. Certainly, it is not as simple as saying, “People have a need for identity and will always attach themselves to what they know, so people will naturally become patriotic”; that claim rests on an overly simplified conception of patriotism. 8. Worldly citizenship and cosmopolitanism 21 It is obvious, upon reflection, that good non-patriotic citizenship is possible, and indeed common. That is demonstrated by the existence of good citizenship among immigrants. The good citizenship of immigrants, I have tried to show, is characteristically of a genuinely different kind from the good citizenship of patriots; it is “worldly citizenship.” In some respects it is preferable to patriotic citizenship, and it is, at least in principle, available to everybody. It follows that those of us who think patriotism inherently flawed should not be rushed to the conclusion that patriotism is needed anyway, because it is needed for good citizenship. At the beginning of the paper, I introduced the idea of worldly citizenship by contrast not just with patriotic citizenship, but also with cosmopolitanism. Unlike the worldly citizen, I said, the cosmopolitan has no attachment to anything more particular than the whole of the world, or the whole of humanity. That construal of cosmopolitanism, however, is really just a (dialectically useful) parody. Nobody could ever have, or want to have, attachments to no particular places or communities at all. The worldly citizen is not a citizen of the world, but the perspective of the worldly citizen is, in one respect, recognizably cosmopolitan. While the worldly citizen need not claim to know the whole world, or even especially to care about the whole world, her view of herself and her country of citizenship is crucially informed by her awareness that the whole world is out there. She does not assume that what is found within one country is thereby “hers,” and that what is found in other countries is not. She has her own home, and her own places and her own communities, but she is, in one respect, open to the world, able to see herself and her attachments from an outside point of view. Cosmopolitanism can look silly and presumptuous when we imagine the cosmopolitan as someone who sees the whole world as his home. You might love 22 Paris as much as Sydney, but if you really want to assert that you are equally at home wherever you are in the world – whether in Paris or Sydney or the street markets of Morocco or the slums of Rio de Janeiro or the mountain villages of the Hindu Kush – then you are either deluded or a liar. A less silly version of the cosmopolitan is someone who recognizes herself to be just one person in the world; who sees the world in terms of lines of similarity and difference that do not follow state and cultural boundaries; who is aware that most of the world is, for her, foreign and unknowable, but also that foreign and unknowable people are humans like her; and who has some idea of how she must appear to people from elsewhere, as well as of how they appear to her. So imagined, I think, the cosmopolitan shares much with the worldly citizen. 17 In that connection, let me finish with a final point in favor of the worldly citizenship, and the related version of cosmopolitanism. In encouraging someone to be patriotic, you will probably encourage her to have beliefs and a self-conception that are, in the end, deluded. When the patriot takes her country as an object of basic loyalty, picturing it as a distinct entity with a distinguishing narrative and purpose and set of defining characteristics, she is almost certain to see her country, and the rest of the world, wrongly. In contrast, when the worldly citizen sees her own local places and communities as special and important, but as placed in a much larger world, she sees them as they really are. The same is true of the respective evaluative dispositions of the patriot and worldly citizen. In the end, what justifies an act is never that it is good “for country.” The country should not be fetishized; it should not be treated as though it matters for its own sake, over and above the people and causes it serves. A citizen who values the 17 See Kwame Anthony Appiah‟s description of “rooted cosmopolitanism,” in The Ethics of Identity (Princeton University Press, 2005), ch. 6. 23 country for its role in serving principles of justice and compassion, and for its importance in protecting and advancing the flourishing of the smaller places and communities for which she cares, ascribes to the country the kind of value that a country really has. 18 18 This paper was originally presented at a conference on patriotism held at Dartmouth College in 2009. I am very grateful for comments received from attendees at the conference, especially Michelle Clarke, Thomas J. Donahue, and William Galston. I am also grateful for helpful comments from Gillian Brock, and from two referees. 24