The Electronic Fire Support Coordinator - MCG

advertisement

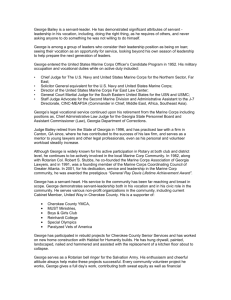

I&I_ Apr11_p12-65:I&IDec06_CHARLENE5.qxd 3/7/11 12:21 PM Page 38 IDEAS & ISSUES (C2) The Electronic Fire Support Coordinator Thinking outside the box by Maj Paul L. Stokes, USMC(Ret) Southeast Asia, 2015 he regimental landing team (RLT) commanding officer (CO) sat in his chair in the landing force operations center (LFOC) and viewed his battle display as his battalions and supporting elements began to execute the coordinated amphibious/air/ground attack. At first things were going well. 1st Battalion seized its objectives quickly via a combined tank/infantry assault launched from the beachhead supported by a 155 battery and a Burke-class destroyer. 3d Battalion disembarked smoothly from the LSDs and LPDs via assault amphibious vehicles and LCACs and quickly seized the port complex that would facilitate the offloading of the follow-on echelon in near record time. But what concerned the CO was 2d Battalion. Its forward command element (FCE) and lead companies were airlifted off the LHD as planned. Even though they lost one CH–53 en route due to a hidden antiaircraft position, the flight leader reported that they landed in Landing Zone (LZ) Dodo (next to a major airport 40 miles inland) without taking any additional fire, and the FCE signaled that they were good to go. But that was over 30 minutes ago, and the FCE has yet to check in on any of the regiment’s radio nets. Suddenly, the air officer tells him the forward air controller (airborne) (FAC(A)) reports observing heavy artillery and small arms fire in/around LZ Dodo, and the second wave has lost two Ospreys to enemy fire. Clearly something has to happen fast, so he tells his S–3 (operations officer) to get the staff together to find out what’s going on. T 38 www.mca-marines.org/gazette >Maj Stokes retired in August 2006 after 31 years of active duty service. A former gunnery sergeant and chief warrant officer 3, he has served in a variety of leadership and communications billets from the team to theater levels. He has served as the Deputy Director for Operations, Marine Corps Communications-Electronics School, since January 2007. The S–3 immediately calls the primary staff together for a hip pocket operational planning team (OPT). He knows that unless command and control (C2) connectivity is reestablished he’s going to lose almost 25 percent of his combat power and hundreds of Marines. The staff includes leaders who are responsible for all of the elements of the RLT, but at this particular moment, the one man who understands how to employ the RLT C2 systems in the most effective manner possible, the . . . the CommO . . . will soon find himself being respected as a tactician. . . . one man who knows how “to make it happen” regardless of what the book says, the one man who can snatch victory from imminent defeat is the electronic fire support coordinator, aka the RLT S–6 communications officer (CommO). That’s right, Marines, the electronic fire support coordinator. For decades the Marine Corps has trained its CommOs/chiefs to be technically proficient. But when it comes to thinking outside the box and em- ploying our communications gear in the same manner as weapons systems, we can do better. For example, when that RLT S–6 arrives at that OPT in the LFOC, he must embrace the fact that he isn’t just a communicator. Rather, he is an expert in employing a supporting arm, just like artillery, mortars, and close air support; the only difference is that his weapons fire electrons vice steel. Or to put it another way, many of the same planning considerations that would be applied to fire support planning (e.g., mission, enemy, terrain and weather, troops and support available-time available; petroleum, oil, lubricants; supply; maintenance personnel; priority of fires) also apply to communications. Ergo, the S– 6 needs to ingrain himself into the planning process by serving in the same manner as the artillery/air officers by advising the CO/S–3 on how he can effectively support the scheme of maneuver with his “electronic artillery.”1 With this approach, the CommO (i.e., the shooter) will soon find himself being respected as a tactician vice a technician, which is a key point. All too often we (the Marine Corps communications community) focus on the technical aspects of communications and forget the fact that our mission is to support the frontline rifleman. This means that we, as communicators, need to dust off our old combat arms manuals from The M a r i n e C o r p s G a z e t t e • A p r i l 2 011 I&I_ Apr11_p12-65:I&IDec06_CHARLENE5.qxd Basic School/Expeditionary Warfare School/Command and Staff College and begin to think like electronic fire support coordinators. There are a number of documents that could help prepare the shooter for this “shift in mindset,” but the first one he should get his hands on is the 1976 version of the old Fleet Marine Force Manual 10–1 (FMFM 10–1), Communications, because this manual is based on over 35 years of combat experience and is designed to pass on those time-tested lessons. Granted, finding that document could take a little time, but it’s worth the effort.2 The shooter should also read the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff Manual 6231 (CJCSM 6231) series of publications, because they are the standard when it comes to joint command, control, communications, and computer (C4) systems. And he shouldn’t be afraid to bring them to an OPT. After all, the artillery/air guys have to use reference pubs in these meetings, so why can’t he bring his? The next thing he needs are copies of the initiating directive, operations order, task organization, force laydown, and concept of operations, since these products will help him understand the command relationships/force structure. With that knowledge, the shooter can create the communications control (CommCon) relationships (i.e., the electronic fire support control structure) that will furnish, install, operate, and maintain the C2 system/network(s) that supports the evolution that is being OPT’d. The remaining things the shooter needs to bring with him are a good sense of humor, patience, and the discipline to stick to his guns. Face it, artillery and air can only do so much, and the CO/G– 3/S–3 will usually accept those limitations without question. Communications (i.e., electronic fire support) should be looked at in the same manner since it can’t be fairy dusted. It either does or doesn’t work. That may be hard for some folks to swallow, but if the shooter can speak in the G/S–3’s terms, then he will soon find himself inside the circle vice out of it. As one can quickly surmise, developing these “battle skills” takes time, M a r i n e C o r p s G a z e t t e • A p r i l 2 011 3/7/11 12:22 PM Page 39 1. Be a leader, first and foremost. 2. Electronic fire support systems (e.g., communications gear) are employed in the same manner as artillery, crew-served weapons, and close air support—the only difference is that they fire electrons not steel. 3. Become an expert in terrain appreciation from the tactical to strategic levels. 4. Understand the command’s mission, capabilities, and limitations. 5. Create a “toolbox” of reference material, and don’t be afraid to bring it to an OPT. 6. When reporting to an OPT, bring a good sense of humor, patience, and the discipline “to stick to your guns” when discussing why a particular course of action is unsupportable. 7. Read as much as you can about battle leadership, tactics, and C2 from the tactical to strategic levels. 8. Learn to think, talk, and brief like an “operator.” 9. Write and publish electronic fire support plans that are clear, concise, and easily adaptable to changes on the battlefield and/or scheme of maneuver. 10. Become an integral part of your respective staff and focus not only on the immediate missions but also prepare for those that always seem to “pop up” when you least expect them. The electronic fire support coordinator’s basic tenets. but if the shooter makes the conscious decision to embark upon a journey of lifelong self-study, he’ll find that the challenges of C4 are nothing new. The hard part is figuring out how to best employ the available electronic fire support systems/personnel. Where does the shooter start? The first step would be embracing the fact that he is a leader first and foremost. Technicians are, quite frankly, a dime a dozen. Ergo, the shooter can’t allow himself to get sucked into the vortex of minutia. Therefore, he should pull out his copy of Marine Corps Warfighting Publication 6–11 (MCWP 6–11), Leading Marines, and read it, study it, and implement it in all of his daily activities. After all, it’s his primary duty as a leader to “take care of Marines and support operations.” The second step would be learning how the operators think. This is a cultivated skill, but if the shooter studies Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1 (MCDP 1), Warfighting; MCDP 1–0, Marine Corps Operations; MCDP 1– 1, Strategy; MCDP 1–2, Campaigning; MCDP 1–3, Tactics; MCDP 2, Intelligence; MCDP 3, Expeditionary Operwww.mca-marines.org/gazette 39 I&I_ Apr11_p12-65:I&IDec06_CHARLENE5.qxd 3/7/11 12:22 PM Page 40 IDEAS & ISSUES (C2) It’s time to think outside the box. (Photo courtesy of author.) ations; MCDP 4, Logistics; MCDP 5, Planning; MCDP 5–1, Marine Corps Planning Process; and MCDP 6, Command and Control, he’ll become an operator in his own right, especially when he finds himself being assigned as the leader of the next OPT. The third step would be to become tactically and technically proficient in the employment of electronic fire support systems. The schoolhouse does a good job teaching technical skills, but to be truly effective, the shooter needs to create a publications “toolbox” (see Table 1) that would contain the tools, techniques, procedures, and technical data that he can use when furnishing, installing, operating, and maintaining C4 systems in support of an operation. Besides the publications we’ve just mentioned, this toolbox would include: MCWP 3–40.3, MAGTF Communications Systems, dated 8 January 2010. This MCWP outlines how the MAGTF communications systems (MCS) provide effective C2 support.3 Headquarters Marine Corps (HQMC) C4 Tri-MEF Communications Standing Operating Procedures (SOP), Version 3, dated 21 October 2009. This SOP “sets the bar” for tac40 www.mca-marines.org/gazette tical C4 systems operations in all three MEFs and serves as a source of MCS technical information.4 Joint Publication 6–0, Joint Communications Systems, dated 20 March 2006. This is an overview of how joint C4 works at the Department of Defense (DoD), combatant command, and joint task force (JTF) levels and includes a comprehensive JTF J–6 planning checklist that can be readily adapted by a MAGTF G–6/S–6. . . . read as much as one can on leadership, operations, fire support, planning, and how to cope with great adversity. The Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) Global Contingency and Exercise Plan (ConExPlan). DISA Network C2 services (secure voice, data, and video) are now being extended down to the company/pla- toon/squad level, which magnifies the planning and engineering challenges faced by the shooter. The ConExPlan provides the guidance, points of contact, and techniques and procedures for accessing/troubleshooting these services via a DoD teleport/standard tactical entry point, making it a valued addition to any S–6’s toolbox. U.S. Army Field Manual 6–02.71 (FM 6–02.71), Network Operations, dated 15 January 2009. This FM explains how the Army conducts network operations (CommCon) from the theater to battalion level, to include a set of corps-level network operations techniques and procedures that directly correlate to the ones that are used by a MAGTF G–6/S–6. The fourth step is to read as much as one can on leadership, operations, fire support, planning, and how to cope with great adversity. In addition to the Marine Corps Professional Reading Program, the shooter should seek out and read the following books and reports. Battle Leadership.5 This book has been a favorite of Marine officers since the 1930s, and its lessons are timeless (e.g., “We must kill institutionalized training otherwise it will kill us!”). Leaders and Battles: The Art of Military Leadership.6 When it comes to military history, the trend is to overlook the human factors that ultimately led to success or defeat. This study “brings to life” these elements and gives the shooter a clear understanding of why the best-laid plans go “haywire” once the first round goes downrange. Edson’s Raiders.7 You’re a senior colonel tasked to create a brand new unit that’s designed to strike the enemy quickly and deeply, and you don’t have the luxury of time to put it all together. That’s the challenge that “Red Mike” Edson faced back in 1941 when he found himself in command of the 1st Marine Raider Battalion—and that’s the same challenge that every electronic fire support coordinator faces when he’s told to throw together a task-organized communications team. So why not learn from the best? M a r i n e C o r p s G a z e t t e • A p r i l 2 011 I&I_ Apr11_p12-65:I&IDec06_CHARLENE5.qxd 3/7/11 12:22 PM Page 41 The Electronic Fire Support Coordinator’s Toolbox 1. MCWP 6–11, Leading Marines 2. MCDP 1, Warfighting 3. MCDP 1–0, Marine Corps Operations 4. MCDP 1–1, Strategy 5. MCDP 1–2, Campaigning 6. MCDP 1–3, Tactics 7. MCDP 2, Intelligence 8. MCDP 3, Expeditionary Operations 9. MCDP 4, Logistics 10. MCDP 5, Planning 11. MCDP 5–1, Marine Corps Planning Process 12. MCDP 6, Command and Control 13. FMFM 10–1, Communications, 24 June 1976 Edition 14. Director C4, Communications Control, Strategy, dated 4 February 2010, HQMC, Washington, DC 15. MCWP 3–40.3, MAGTF Communications System, dated 8 January 2010 16. HQMC C4 Tri-MEF Communications Standard Operating Procedures (SOP), Version 3, dated 21 October 2009 17. Joint Publication 6–0, Joint Communications System, dated 20 March 2006 18. The CJCSM 6231 Series of Publications 19. DISA Global ConExPlan 20. FM 6–02.71, Network Operations, dated 15 January 2009 21. Joint Forces Command JTF Communications Officer (J6) Handbook, dated 7 August 2002 Table 1. The toolbox. M a r i n e C o r p s G a z e t t e • A p r i l 2 011 Easter Offensive.8 It is 1972 in Vietnam. You’re an advisor on your first inspection tour visiting the 3d Division Headquarters, Army of the Republic of Vietnam, just south of the demilitarized zone, which just happens to be the same day that the North Vietnamese Army launches its Easter offense. The next thing you know you’re coordinating the defense of the Northern Provinces of an entire nation. LtCol G.H. Turley entered this crucible, succeeded, and left behind a story that will teach any leader how to cope with events that would crush a lesser man. As any successful MAGTF G–6/S–6 will tell you, overcoming adversity is a daily occurrence when it comes to electronic fire support. Guadalcanal: The Definitive Landmark Account.9 Guadalcanal was the last time the United States fought a determined enemy in an expeditionary environment, without the luxury of air/sea/ground superiority, thus forcing our Marines, sailors, soldiers, and airman to think “out of the box,” lead from the front, and employ tactics, techniques, and procedures that ultimately led to victory. This operational history is exactly what its title implies. It is the definitive account. Joint Air Operations: Pursuit of Unity in Command and Control, 1942–1991.10 If there is no communications, there is no aviation C2, which means that the shooter must immerse himself in the nuances of joint air operations. This RAND study is the best analysis I’ve read on how Marine aviation is affected by national policy, technology, and resources. A Bias for Action: The 7th Panzer Division in France and Russia, 1940– 1941.11 The German Army was so successful in World War II because its commanders/staffs used a common doctrine that stressed initiative, critical thinking, and the willingness to make decisions at the lowest practical level. One can learn much from this treatise since it explains how leaders interact as they successfully execute mobile combat operations. www.mca-marines.org/gazette 41 I&I_ Apr11_p12-65:I&IDec06_CHARLENE5.qxd 3/7/11 12:23 PM Page 42 IDEAS & ISSUES (C2) Under the Red Sea Sun.12 It’s midDecember 1941. You’ve been sent to British-occupied Italian East Africa to rebuild the port of Massawa—one of the hottest places on the planet—with nothing much more than the verbal order “to make the port operational ASAP.” That is the challenge that CDR Edward Ellsberg faced, and this is the best memoir I’ve ever read on how to do the impossible with little to no resources. The shooter may find himself in similar circumstances, and knowing that aggressive leadership can overcome any obstacle will make him that much more effective. a level of success that may have evaded him in the past. Because quite frankly, learning the technical skills of C4 is the easy part. The real challenge lies in effectively leading Marines. Southeast Asia, 2015 The OPT started rough and after several tirades from his fellow staff members the electronic fire support coordinator (aka RLT S–6) checked the RLT’s radio plan then recommended that the RLT air officer call the FAC(A) to see if he still had contact with the 2d Battalion FCE’s tactical air control Because quite frankly, learning the technical skills of C4 is the easy part. Operation Stabilise: Australian East Timor Operations: September 1999– December 1999.13 You’re a Marine captain 0602 on your way to Australia. The next thing you know you’re ordered to report for duty as the J6 future operations officer to the U.S. component of an Australian-led, United Nations-sanctioned combined task force. Does that sound like a challenge for any leader, let alone the shooter? You bet it does, and these reports provide a firsthand view of just how complicated C2 becomes in a coalition operation. The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars in the Midst of a Big One.14 To defeat the enemy one must first understand him. This modern classic on global insurgencies is absolutely invaluable to learning how to be successful in this era of “violent peace.” The fifth step is to become an integral part of your respective staff and focus not only on the immediate missions but also on preparing for the ones that always seem to “pop up” when you least expect them. This is the essence of electronic fire support, and if the shooter makes the determined effort to become a combat leader he will realize 42 www.mca-marines.org/gazette party (TACP). Five minutes went by and the air officer confirmed that he did; immediately the RLT S–6 recommended that they set up a voice radio relay between the TACP, the FAC(A), and the LFOC. The RLT S–3 nodded in agreement. C2 was reestablished with the remnants of the 2d Battalion FCE, and a potential disaster was adverted. Was the solution a throwback back to days of Higgins boats and LVT–1 alligators? Maybe so, but that’s why you have an electronic fire support coordinator—to think outside the box when the plan goes out the window! Notes 1. Electronic artillery: long-range—ground mobile forces satellite communications systems (i.e., Phoenix, secure mobile antijam reliable tactical-terminal, secure wide area network, and lightweight multiband satellite terminal); medium range—TRC–170 super high-frequency troposcatter radio transmission systems; short range—MRC–142 mircrowave radio transmission systems, mobile and manpacked single-channel radio systems, and tactical telephone and computer systems. 3. MCWP 3–40.3, MAGTF Communications System, dated 8 January 2010, p. 1–1, paraphrased. The MCDPs cited in this article were published by the Department of the Navy, HQMC, Washington, DC. 4. HQMC C4 Tri-MEF Communications SOP, Version 3, dated 21 October 2009, p. 3, paraphrased. 5. Von Schell, Capt Adolf, Battle Leadership, Staff Corps, German Army, The Benning Herald, Fort Benning-Columbus, GA, 1933, reprinted by The Marine Corps Association, Quantico, 1982. 6. Wood, W.J., Leaders and Battles: The Art of Military Leadership, Presidio Press, New York, 1984. 7. Alexander, Col Joseph H., USMC(Ret), Edson’s Raiders: The 1st Marine Raider Battalion in World War II, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2001. 8. Turley, Col G.H., USMCR(Ret), The Easter Offensive: The Last American Advisors, Vietnam, 1972, Presidio Press, 1985, reprinted by Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1995. 9. Frank, Richard B., Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle, Random House, New York, 1990. 10. Winnefeld, James A., and Dana J. Johnson, Joint Air Operations: Pursuit of Unity in Command and Control, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1993. 11. Stolfi, Dr. Russell H.S., “A Bias for Action: The German 7th Panzer Division in France and Russian, 1940–1941,” Marine Corps University Perspectives on Warfighting, Number One, Command and Staff College Foundation, Quantico, 1991. 12. Ellsberg, CDR Edward, USNR, Under the Red Sea Sun, Dodd, Mead & Company, New York, 1946. 13. Operation Stabilise: Australian East Timor Operations: September 1999–December1999, DISA-PAC PC32 Combined Reports, dated 14 January 2000, Marine Corps Lessons Learned System Reference Number 4562. 14. Kilcullen, David, The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars in the Midst of a Big One, Oxford University Press, 2009. 2. The Gen Alfred M. Gray Research Center at Marine Corps Base Quantico has this document on file. M a r i n e C o r p s G a z e t t e • A p r i l 2 011