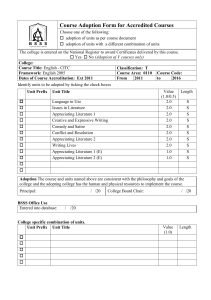

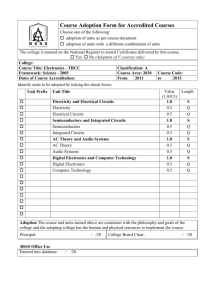

The Uniform Adoption Act

advertisement