(Re)Educating for Leadership

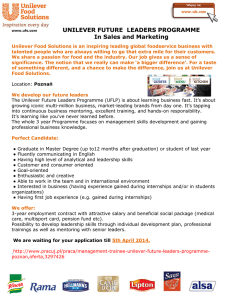

advertisement