The American Journal of Surgery (2013) 206, 739-747

Clinical Science

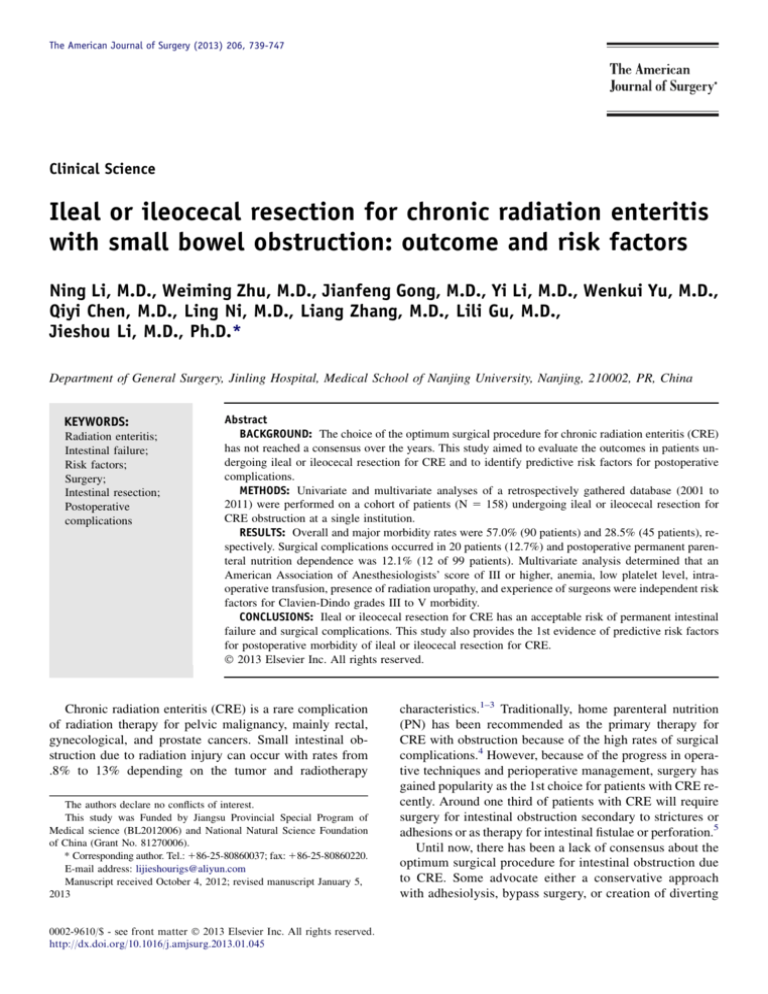

Ileal or ileocecal resection for chronic radiation enteritis

with small bowel obstruction: outcome and risk factors

Ning Li, M.D., Weiming Zhu, M.D., Jianfeng Gong, M.D., Yi Li, M.D., Wenkui Yu, M.D.,

Qiyi Chen, M.D., Ling Ni, M.D., Liang Zhang, M.D., Lili Gu, M.D.,

Jieshou Li, M.D., Ph.D.*

Department of General Surgery, Jinling Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210002, PR, China

KEYWORDS:

Radiation enteritis;

Intestinal failure;

Risk factors;

Surgery;

Intestinal resection;

Postoperative

complications

Abstract

BACKGROUND: The choice of the optimum surgical procedure for chronic radiation enteritis (CRE)

has not reached a consensus over the years. This study aimed to evaluate the outcomes in patients undergoing ileal or ileocecal resection for CRE and to identify predictive risk factors for postoperative

complications.

METHODS: Univariate and multivariate analyses of a retrospectively gathered database (2001 to

2011) were performed on a cohort of patients (N 5 158) undergoing ileal or ileocecal resection for

CRE obstruction at a single institution.

RESULTS: Overall and major morbidity rates were 57.0% (90 patients) and 28.5% (45 patients), respectively. Surgical complications occurred in 20 patients (12.7%) and postoperative permanent parenteral nutrition dependence was 12.1% (12 of 99 patients). Multivariate analysis determined that an

American Association of Anesthesiologists’ score of III or higher, anemia, low platelet level, intraoperative transfusion, presence of radiation uropathy, and experience of surgeons were independent risk

factors for Clavien-Dindo grades III to V morbidity.

CONCLUSIONS: Ileal or ileocecal resection for CRE has an acceptable risk of permanent intestinal

failure and surgical complications. This study also provides the 1st evidence of predictive risk factors

for postoperative morbidity of ileal or ileocecal resection for CRE.

Ó 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Chronic radiation enteritis (CRE) is a rare complication

of radiation therapy for pelvic malignancy, mainly rectal,

gynecological, and prostate cancers. Small intestinal obstruction due to radiation injury can occur with rates from

.8% to 13% depending on the tumor and radiotherapy

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study was Funded by Jiangsu Provincial Special Program of

Medical science (BL2012006) and National Natural Science Foundation

of China (Grant No. 81270006).

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 186-25-80860037; fax: 186-25-80860220.

E-mail address: lijieshourigs@aliyun.com

Manuscript received October 4, 2012; revised manuscript January 5,

2013

0002-9610/$ - see front matter Ó 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.01.045

characteristics.1–3 Traditionally, home parenteral nutrition

(PN) has been recommended as the primary therapy for

CRE with obstruction because of the high rates of surgical

complications.4 However, because of the progress in operative techniques and perioperative management, surgery has

gained popularity as the 1st choice for patients with CRE recently. Around one third of patients with CRE will require

surgery for intestinal obstruction secondary to strictures or

adhesions or as therapy for intestinal fistulae or perforation.5

Until now, there has been a lack of consensus about the

optimum surgical procedure for intestinal obstruction due

to CRE. Some advocate either a conservative approach

with adhesiolysis, bypass surgery, or creation of diverting

740

The American Journal of Surgery, Vol 206, No 5, November 2013

stomas without resection of the primary lesion or a more

radical operation with resection of the diseased segment of

the bowel. Although resectional surgery has been shown

to cause a higher incidence of leakage and mortality than

bypass, diseased bowel left behind can cause bleeding and

can result in perforation and fistulization, and, therefore, a

need for reoperation. Several studies have suggested

liberal resection of the affected bowel as the preferable

therapy.5–7 According to a recent article by Lefevre et al,8

ileocecal resection is the only factor that protected against

reoperation for recurrent CRE, which demonstrates the

importance of resecting all damaged tissue in patients

with CRE. An early study suggested that resectional surgery had a similar mortality but decreased reoperation

rates and the ultimate need for long-term PN compared

with a nonresection group.9 Perrakis et al10 also reported

a favorable outcome without disease recurrence of 17 patients treated by resection of the diseased bowel segment.

However, the early and long-term outcomes, postoperative

complications, and risk factors for early postoperative

complications of ileal or ileocecal resection for CRE are

unknown in large cohort studies.

In our department, resection of the irradiated small

bowel lesion causing obstruction is the primary surgical

option for CRE with intestinal obstruction. The aim of the

current study was to evaluate the early postoperative and

long-term outcomes in patients with ileal or ileocecal

resection for diseased intestinal segments of radiation

enteritis, and we analyzed the risk factors for postoperative

complications.

Methods

Patients

Adult patients who had undergone ileum or ileocecal

resection for CRE with intestinal obstruction from January 2001 to December 2011 were retrospectively analyzed. Clinical data were collected from medical case

records. All patients had postoperative pathologic diagnosis of CRE. CRE patients with uncured malignancy (n

5 50), conservative treatment but not surgery (n 5 44),

isolated colorectal lesions (n 5 39), intestinal fistula (n 5

82), or patients undergoing bypass (n 5 6) and stoma

surgery without resection (n 5 2) were not included for

analysis.

Patients’ demographic and clinical data include previous

malignancy, type of tumor surgery, total dosage and type of

radiotherapy, concomitant chemotherapy, and surgical parameters. History of smoking, diabetes, and previous

abdominal surgery were also considered as demographic

data. Postoperative hospital stay was also recorded. For

nutritional risk screening, recent weight loss (compared to

preillness),11 body mass index (BMI), and serum albumin

level were used. Approval of the study was obtained from

the ethics committee of Jinling Hospital.

Risk factors

With reference to the studies by Lefevre et al,8 Chen

et al,12 and Regimbeau et al,5 34 demographic and clinical

variables accounting for possible influence on the perioperative period were recorded: age (660 years); sex (male/female); presence of acute radiation enteritis (grade I to

III)13; radiation dosage (cumulative dosage of external and

endocavitary radiation, .50 Gy vs %50 Gy); concomitant

chemotherapy; intraperitoneal chemotherapy; latency of disease (%6 m vs .6 m); time from disease onset to surgery

(%5 m vs .5 m); BMI (,17.5 kg/m2); significant weight

loss (defined as a 10% decrease in weight upon comparison

of the patient’s preillness); low BMI and significant weight

loss (BMI , 17.5 kg/m2 and weight loss R 10%); American

Association of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification score

III to IV; gynecologic malignancy; abdominoperineal resection; history of smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and

abdominal surgery prior to radiation; presence of radiation

uropathy (ureter obstruction, radiation cystitis Rgrade II according to the scale devised by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group,14,15 history of ileal neobladder and renal

insufficiency with serum creatine [SCr . 110 umol/L]);

the presence of radiation proctitis16; history of surgery aiming at solving CRE; intraoperative blood transfusion R400

mL; preoperative albumin (Alb , 35 g/L vs Alb R 35 g/L);

preoperative white blood cell count (R10,000/mm3, R3,500

,10,000/mm3, or ,3,500/mm3); preoperative platelet count

(R100 ! 109/L vs ,100 ! 109/L); preoperative anemia

(,12 g/dL in males and ,11 g/dL in females); preoperative

total PN dependence; preoperative intestinal decompression

(with nasointestinal tube, long-intestinal tube, or percutaneous endoscopic gastrotomy with jejunal extension); anastomosis fashion (stapled side-to-side vs stapled end-to-side);

site of resection and anastomosis (ileocecal vs ileal); length

of operation (.3 hours vs %3 hours); and surgeons’ experience (,40 cases vs R40 cases). A fast track recovery (FCS)

protocol was employed in 2007, and we also included the

time of surgery (before and after 2007) for risk factor

analysis.

Postoperative complications

Postoperative morbidity was graded according to the

Clavien-Dindo classification, as described by Lefevre et al.8

For patients undergoing a staged operation (ie, stoma in the

1st operation and stoma reversal in the 2nd operation), the

complication rate was calculated as the total events encountered in 2 operations, but length of postoperative stay was

recorded only for the 1st operation. Dependence on total

PN postoperatively for over 2 weeks was considered as

postoperative morbidity according to the upgraded

Clavien-Dindo classification in 2004.17 Postoperative short

bowel syndrome was defined as a remnant small bowel

length of 180 cm or less with associated malabsorption, according to Boland et al.18

N. Li et al.

Ileal/ileocecal resection for CRE

Surgical complications include anastomotic leakage,

intra-abdominal abscess, postoperative peritonitis, wound

dehiscence, and intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Incomplete

resection of the lesions causing postoperative obstruction

was also considered a surgical complication.

Follow-up

All patients were followed for over 3 months. Obstruction recurrence and reoperation for CRE were recorded.

Patients’ tumor status, BMI, body weight change, dependence on PN, enteral nutrition, and usage of antidiarrhea

agents were also documented. Survival status was evaluated

by review from the medical database and by telephone

follow-up of all patients who had no regular postoperative

outpatient visits for more than 3 months.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with the Statistical Package

for Social Sciences version 13.0 software (SPSS, Chicago,

IL). Consecutive data were presented as mean with standard

deviation or median (range). Statistical analysis was performed by the Mann–Whitney U test or Student’s t test for

continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables as appropriate. Potential risk factors for

postoperative complications were evaluated by univariate

analysis, and risk factors with a univariate probability of

less than .1 were included in the multivariate analysis using

multivariate logistic regression analysis. A probability value

of less than .05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Clinical data

A cohort of 158 consecutive patients (32 males and 126

females) was included in the study from January 2001 to

December 2011. Patients’ characteristics are listed in

Table 1.The main primary malignancy was gynecological

(112 patients, 70.9%) and rectal cancers (37 patients,

23.4%). Patients’ median age on surgery was 51.0 (23 to

82) years and the mean preoperative BMI was 18.08 6 2.86

(12.1 to 29.4) kg/m2. The mean radiation dosage was 55.97

6 15.93 (20 to 128) Gy. The majority of the patients

(n 5 136, 86.1%) had a postoperative radiation therapy. Prior

to surgery, 60 patients (38.0%) were dependent on total PN.

Surgical procedures

The surgical procedures were performed a median of 5

(1 to 157) months after the 1st onset of symptoms for CRE.

The majority of the patients were classified as American

Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) grade II (n 5 91,

57.6%) or III (n 5 48, 30.4%).

741

Table 1 Demographics of 158 patients receiving ileal or

ileocecal resection for chronic radiation enteritis obstruction

Patients’ demographics

Median age (years, range)

Gender (male/female)

Type of primary malignancy, n (%)

Rectal carcinoma/lymphoma

Cervical carcinoma

Ovary cancer

Endometrial cancer

Tubal cancer

Ovary and endometrial cancer

Cervical and rectal cancer

Ovary and rectal cancer

Seminoma

Others

Radiation therapy, n (%)

Radical irradiation (cervical cancer/

rectal lymphoma)

Preoperative

Postoperative

Pre- and postoperative

Radical irradiation and postoperative

Cumulative delivered dosage of RT, Gy,

mean, SD (range)*

Presence of acute radiation enteritis, n (%)

Median latency period (months, range)†

BMI (kg/m2) prior to surgery, n (%)

,17.5

17.5–22

R22

Body weight loss compared to

preillness, n (%)

.10%

%10%

Unknown

Concomitant radiation uropathy, n (%)

Radiation proctitis, n (%)

Previous surgery aiming at CRE with

obstruction, n (%)

Associated risk factors for CRE, n (%)

Diabetes mellitus

Smoking

Hypertension

Previous abdominal surgery

51.0 (23–82)

32/126

36/1 (22.8/.6)

79 (50.0)

7 (4.4)

24 (15.2)

1 (.6)

1 (.6)

1 (.6)

1 (.6)

4 (2.5)

3 (1.9)

14/1 (8.9/.6)

4 (2.5)

136 (86.1)

2 (1.3)

1 (.6)

55.97 6 15.93

(20–128)

64 (40.5)

6 (2–276)

73 (46.2)

73 (46.2)

12 (7.6)

89

56

13

16

20

25

(56.3)

(33.5)

(10.1)

(10.1)

(12.7)

(15.8)

4

16

8

47

(2.5)

(10.1)

(5.1)

(29.7)

BMI 5 body mass index; CRE 5 chronic radiation enteritis;

RT 5 radiation therapy; SD 5 standard deviation.

*Radiation dosage unclear in 26 cases.

†

Five patients presents with symptoms of CRE in 2 months.

Details of the surgical procedure are shown in Table 2.

All patients received open surgery; 143 (90.5%) had a 1stage operation, while staged operation was adopted in 15

(9.5%) patients. The overall (P 5 .844) and major (grade

III to V) (P 5 .863) morbidity did not differ between the

2 groups.

Ileocecal resection or anastomosis was performed in 75

(47.5%) patients, while ileum resection or anastomosis was

performed in 60 (38.0%) patients; 4 (2.5%) had combined

742

The American Journal of Surgery, Vol 206, No 5, November 2013

Table 2 Surgical parameters of ileal or ileocecal resection for

chronic radiation enteritis with obstruction

Table 3 Postoperative morbidity according to Clavien-Dindo

classification

Surgical parameters

Clavien-Dindo classification

No. of patients

Grade I

Ileus

Delayed gastric emptying

Diarrhea

Incisional infection

Grade II

Total parenteral nutrition for over

2 weeks

Catheter infection

Early postoperative obstruction

Grade III

Cholestasis and biliary drainage

Pleural effusion and drainage

Intra-abdominal/pelvic abscess

Anastomotic leak

Intra-abdominal hemorrhage

Gastrointestinal hemorrhage

Would infection/bleeding/dehiscence

Pneumothorax and chest drainage

Incomplete resection and reoperation

Early postoperative obstruction

Ureter obstruction and J-tube placement

Deep vein thrombosis

Grade IV

Respiratory failure

Intra-abdominal hemorrhage and

respiratory failure

Pelvic abscess and renal failure

Anastomotic leak and renal failure

Heart failure

Circulation collapse needing vasoactive

drugs and ICU

Grade V

25 (15.82%)

2

1

16

6

20 (12.66%)

12

Preoperative ASA grade, n (%)

ASA II

ASA III

ASA IV

Mean operation time (minutes),

mean 6 SD (range)

Surgical procedure, n (%)

Ileocecal resection/anastomosis

Ileal resection/anastomosis

Ileal and ileocecal resection/anastomosis

Resection with permanent ileostomy

Ileal/ileocecal resection/anastomosis and

colonic stoma, n (%)

Operative strategy, n (%)

One-stage operation

Two-stage operation

Median postoperative hospital stay

(days, range)

Postoperative short bowel, n (%)

120–180 cm

60–120 cm

%60 cm

No. of patients

91 (57.6)

48 (30.4)

8 (5.1)

164.5 6 40.6

(105–300)

75

60

4

19

16

(47.5)

(38.0)

(2.5)

(12.0)

(10.1)

143 (90.5)

15 (9.5)

13 (4–110)

13 (8.2)

8 (5.1)

2 (1.3)

ASA 5 American Association of Anesthesiologists; SD 5 standard

deviation.

ileum and ileocecal resection, and the remaining 19

(12.0%) patients had diseased lesion resection and permanent ileostomy. Patients who had a permanent ileostomy

had an increased but not significant percentage of ASA

grades III and IV patients (10 of 19 vs 93 of 45/138; P 5

.086), but no difference in overall (P 5 .583) and major

morbidity (P 5 .809) compared with those with anastomosis. Sixteen (10.1%) patients needed concomitant colonic

stoma for sigmoid-rectal stenosis (n 5 12), severe radiation

proctitis (n 5 3), and rectovaginal fistula (n 5 1).

Surgical outcomes

The median postoperative stay was 13 (4 to 110) days.

Since 2007, a fast track recovery (FCS) protocol has been

adopted, which significantly reduced the length of postoperative hospital days (24.07 6 16.59 [6 to 80] days before

2007 vs 16.59 6 14.02 [4 to 110] days after 2007; P 5.013).

Sixty-eight (43.0%) experienced no adverse events and

recovered uneventfully; 184 episodes of postoperative

complications occurred in 90 patients (57.0%). The overall

and major (grades III to V) postoperative morbidity were

57.0% (n 5 90) and 28.5% (n 5 45), respectively.

Postoperative morbidity according to Clavien-Dindo classification is listed in Table 3. Postoperative mortality occurred in 3 patients (1.9%): 1 patient from uncontrolled

intra-abdominal hemorrhage, and the other 2 died of severe

intra-abdominal sepsis and pulmonary fungal infection,

respectively.

7

1

33 (20.89%)

3

4

5

3

2

2

7

1

2

2

1

1

9 (6.70%)

3

1

1

1

1

2

3 (1.89%)

Anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal abscess, intestinal

fistula or postoperative peritonitis, wound dehiscence, and

intra-abdominal hemorrhage were observed in 19 episodes

in 17 patients (10.8%). Incomplete resection causing postoperative intestinal obstruction was observed in 3 patients

(1.9%). The overall surgical complication was 12.7% (20

patients). Thirteen patients (8.2%) required relaparotomy

for postoperative complications.

Risk factors for postoperative complications

Table 4 shows the perioperative factors analyzed in a

univariate way to detect their influence on postoperative

morbidity.

On univariate analysis, an ASA score of III or IV (P 5

.001), intraoperative transfusion 400 mL or more (P 5

.011), and preoperative platelet count less than 100 !

109/L (P 5 .009) had a significant contribution in overall

postoperative morbidity. Compared with other tumors,

CRE surgery after gynecologic malignancy had less

N. Li et al.

Table 4

Ileal/ileocecal resection for CRE

743

Univariate analysis of factors associated with postoperative complications

Variables

No. of patients

Overall morbidity

P

Grade III–V

P

Age (years)

Sex

Acute radiation enteritis

Radiation dosage (Gy)*

Concomitant chemotherapy

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy

Latency period (months)

Symptom onset to referral (months)

BMI (kg/m2)

Weight loss compared to preillness

BMI , 17.5 kg/m2 and weight loss R 10%

ASA score

Gynecological malignancy†

APR

Previous abdominal surgery

Smoking history

Diabetes mellitus

Hypertension

Radiation uropathy (include SCr .110 umol/L)

Radiation proctitis

Previous surgery for CRE

Intraoperative transfusion

Preoperative albumin

Preoperative WBC count (!109/L)

Preoperative WBC count (!109/L)

Preoperative platelet count (!109/L)

Preoperative anemia (,11 (female)/12

(male) g/dL)

Preoperative TPN dependence

Preoperative intestinal decompression

Anastomotic fashion

Resection and anastomosis site‡

Operation time (hours)

Surgery before 2007

Experience of the surgeon (cases)

,60/R60 (127/31)

Male/female (32/126)

Yes/No (64/94)

%50/.50 (77/55)

Yes/No (91/67)

Yes/No (6/152)

%6/.6 (79/79)

%5/.5 (80/78)

,17.5/R17.5 (73/85)

R10%/,10% (89/56)

Yes/No (49/96)

III–IV/I–II (56/102)

Yes/No (112/44)

Yes/No (23/135)

Yes/No (47/111)

Yes/No (12/146)

Yes/No (4/154)

Yes/No (8/150)

Yes/No (16/142)

Yes/No (20/138)

Yes/No (25/133)

R400 mL/,400 mL (10/148)

,35 g/L/R35 g/L (41/117)

,3.5/R3.5, ,10 (57/95)

R10/R3.5, ,10 (6/95)

,100/R100 (16/142)

Yes/No (96/62)

71/19

20/0

42/48

41/36

51/39

1/89

48/42

41/49

45/45

54/30

32/52

42/48

57/31

17/73

30/60

8/82

2/88

5/85

12/78

14/76

20/70

9/81

28/62

29/56

5/56

15/75

56/34

.587

.479

.070

.161

.786

.042

.335

.177

.977

.339

.199

.001

.027

.076

.257

.480

.766

.745

.124

.208

.011

.029

.099

.322

.236

.009

.665

34/11

9/36

19/26

21/17

26/19

0/45

21/24

20/25

23/22

24/17

15/27

27/18

27/16

10/35

12/33

5/40

2/43

3/42

11/34

13/32

11/34

8/37

14/31

17/25

3/25

11/34

33/12

.335

.940

.782

.649

.977

.115

.484

.326

.435

.659

.755

.000

.123

.085

.593

.292

.334

.562

.000

.000

.061

.000

.366

.529

.209

.000

.041

Yes/No (60/94)

Yes/No (59/95)

Stapled SSA/ESA (82/57)

Ileal/ileocecal (60/75)

%3/.3 (129/29)

Yes/No (29/129)

,40/R40 (75/83)

36/54

33/57

44/34

33/42

69/21

21/69

53/37

.754

.619

.484

.908

.063

.063

.000

20/25

20/25

24/16

14/19

31/14

11/34

27/18

.370

.244

.878

.788

.009

.212

.047

APR 5 abdominoperineal resection; ASA 5 American Association of Anesthesiologists; BMI 5 body mass index; CRE 5 chronic radiation enteritis;

ESA 5 end-to-side anastomosis; SCr 5 serum creatine; SSA 5 side-to-side anastomosis; TNP 5 total parenteral nutrition; WBC 5 white blood cells.

*Radiation dosage unknown in 26 patients.

†

Two patients had combined gynecological and rectal cancer were not included for analysis.

‡

Nineteen patients had permanent ileostoma, and 4 patients had combined ileal and ileocecal resection (2 anastomosis). They are excluded for

analysis.

postoperative morbidities (39.28% vs 54.39%, P 5 .027).

Patients who had previously undergone surgery for CRE

also had a significant increased risk for postoperative morbidity (80.00% vs 52.63%, P 5 .011). Among surgeons, the

experienced surgeons (R40 cases) had significantly fewer

postoperative complications (44.58% vs 70.67%, P ,

.001) compared with the less-experienced group.

Significant predictive factors for major (grades III to V)

postoperative morbidity include an ASA score of III or IV

(P , .001), concomitant radiation uropathy (including SCr

.110 umol/L, P , .001), radiation proctitis (P , .001), preoperative platelet count less than 100 ! 109/L (P , .001),

preoperative anemia (,110 g/L in females and ,120 g/L

in males, P 5 .041), intraoperative transfusion 400 mL or

more (P , .001), operation time longer than 3 hours (P 5

.009), and less-experienced surgeons (P 5 .047).

After univariate analysis, variables with a probability

value less than .1 were selected for multivariate analysis

using a multivariate logistic regression model. Table 5 summarizes the results of multivariate analysis. An ASA score

of III or IV, previous surgery for CRE, and lack of surgical

experience were predictive of overall morbidity in ileal or

ileocecal resection for CRE. Additionally, an ASA score

of III or IV, the presence of radiation uropathy, intraoperative transfusion, decreased platelet count, preoperative anemia, and less-experienced surgeons were independent

predictors for developing major (grades III to V) postoperative complications.

744

Table 5

The American Journal of Surgery, Vol 206, No 5, November 2013

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with postoperative complications

Overall morbidity

Variables

P

Acute radiation enteritis

ASA score

Gynecological malignancy

APR

Radiation uropathy

Radiation proctitis

Previous surgery for CRE

Intraoperative transfusion

Preoperative albumin

Preoperative platelet count

Preoperative anemia

Operation time (hours)

Surgery before 2007

Experience of the surgeon

.126

.037

.235

.827

.043

.056

.351

.142

.895

.239

.001

Grades III–V morbidity

OR (95% CI)

P

2.46 (1.06–5.74)

.010

3.54 (1.04–12.09)

.917

.002

.639

.613

.014

.011

.030

.372

.26 (.11–.57)

.018

OR (95% CI)

3.34 (1.34–8.35)

10.97 (2.39–50.26)

11.70 (1.63–83.76)

6.46 (1.54–27.14)

3.38 (1.13–10.16)

.30 (.11–.81)

APR 5 abdominoperineal resection; ASA 5 American Association of Anesthesiologists; CI 5 confidence interval; CRE 5 chronic radiation enteritis;

OR 5 odds ratio.

Follow-up

Of the 155 patients discharged, 119 (74.8%) were on

follow-up. Nineteen patients (12.3%) died of tumor recurrence during follow-up. One patient who could not wean off

PN died of PN-related complications 6 years after discharge.

The median follow-up was 20.0 (3 to 128) months for the

remaining 99 patients (with 2 tumor recurrence).

Postoperative short bowel, defined as residual small

bowel length 180 cm or less, was observed in 23 patients

(14.6%). Among them, 2 patients had remnant small bowel

length 60 cm or less. At the end of follow-up, 12 patients

(12.12%) were permanently dependent on PN. Twenty

patients (20.2%) used antidiarrhea agents intermittently and

17 patients (17.17%) were supplemented with enteral

nutrition. Patients’ BMIs were 20.17 6 3.01 (12.33 to

27.94) kg/m2 on last follow-up vs 17.61 6 2.96 (12.11 to

29.41) kg/m2 prior to surgery (paired t test, P , .01).

Six patients (6.1%) had recurrent intestinal obstruction

after surgery; 1 (1.0%) patient developed radiation cystitis

2 years after discharge.

Comments

In this cohort study, we retrospectively analyzed the

clinical outcomes and risk factors of ileal or ileocecal

resection for patients with CRE in a specialized and highvolume gastrointestinal surgery center. The study had a

median follow-up of 20 months and revealed that the

aggressive resection for CRE with intestinal obstruction

could be adopted with an acceptable incidence of postoperative permanent intestinal failure (12.12%) and surgical

complications (12.7%). The cohort in this study is a rather

homogenous group with patients with only intestinal

obstruction and surgical resection included. This is the

1st study specially exploring the clinical outcome and risk

factors of resectional surgery for CRE obstruction.

A main concern for primary ileal or ileocecal resection

in CRE is the high morbidity rate. Earlier literature reported

that postoperative complications, particularly anastomotic

leaks, can occur in up to 30%, and 40% to 60% of patients

will require more than 1 laparotomy.19 In another large cohort study (77 resections in 107 patients) by Lefevre et al,8

the overall morbidity, mortality, and surgical postoperative

morbidity rates from 1980 to 2009 were 74.8%, .9%, and

28.0%, respectively. Reappraisal of the surgical treatment

of CRE in 48 patients (37 resections) by Onodera et al7

from 1975 to 2003 reported a morbidity of 21.7% and mortality of 4.1%. A similar finding of 5% mortality and 29%

morbidity was also reported by Regimbeau et al5 after 65

bowel resections for radiation enteritis from 1984 to

1994. In the present study, with postoperative total PN dependence longer than 2 weeks included, postoperative morbidity was observed in 56.96% of the patients, with major

(grade III or IV) morbidity in 28.48% and overall mortality

1.89%, indicating that ileal or ileocecal resection for CRE

is still an operation with a high morbidity rate. Surgical

rate of complications in the current study is 12.7% (including 3 incomplete resections), which is lower than the results

of previous studies. Because the majority of the data in previous studies were either obtained before 2003 or over a

long period of time (30 years by Lefevre et al8) and the surgical techniques and perioperative care have evolved dramatically in recent years, this might explain the decreased

postoperative complication rate in the current cohort. Actually, morbidity rates have decreased in our department since

2007, although not statistically significantly (P 5 .063).

Also, we believed that a specialized high-volume center

(average more than 15 patients per year in our hospital)

might be helpful in reducing complications after such a

high-risk surgery.20

N. Li et al.

Ileal/ileocecal resection for CRE

Incidence of intestinal failure after surgical intervention

for radiation-induced bowel injury varies among studies.

According to Regimbeau et al,5 PN dependence was observed in 32% of patients who underwent resection surgery

compared with 38% in the conservative group, after a

follow-up of a median of 40 months. In another retrospective study by Gavazzi et al,21 10 of 17 patients (58.8%) who

underwent surgery eventually developed intestinal failure,

but the type of the operation was not mentioned in their article. In a large cohort by Lefevre et al,8 the incidence of

permanent home PN is 49.5% in 104 patients. The incidence of short bowel after surgery is 14.56% and permanent intestinal failure is 12.12% in the current cohort,

which are both lower than in previous studies. However,

this was at the cost of an incomplete resection in 3 cases

(1.9%), but fortunately not increased anastomosis leakage.

As preoperative enteroclysis is carried out in our department, it is useful for evaluation of obstruction site and

length of remaining healthy small bowel, which might

help to avoid excessive resection and maximally preserve

the small bowel length. Another explanation for the reduced intestinal failure rate might be the advancement of

irradiation techniques in recent years, such as intensitymodulated radiotherapy, which can decrease the small

bowel dosage and chronic gastrointestinal toxicity and

thereby the extent of injured bowel for resection.22

Identifying risk factors that may influence the patient’s

outcome may be helpful for the success of ileal or ileocecal

resection for CRE. However, until now no such study has

been conducted. In this current study, we analyzed 34

possible factors that may influence outcome for CRE ileal

or ileocecal resection. Consistent with previous studies in

surgery, our results revealed that a preoperative ASA score

of III or higher and intraoperative transfusion are associated with increased overall and major complications.

Preoperative anemia also contributed to increased risk

(OR 3.38) for major morbidity. Therefore, preoperative

anemia should be corrected, and diagnosis and improvement of decompensated comorbidities should also be

properly adjusted before CRE ileal or ileocecal resection

to minimize the risk.

The history of previous surgery aimed at solving CRE

obstruction as an independent factor (OR 3.54) emphasized

the importance of referring CRE patients to a specialized

center for initial surgical treatment. The impact of the

surgeon’s experience on surgical outcome has been well

recognized in various procedures.23,24 As ileal or ileocecal

resection is technically demanding, with high morbidity

rates, we examined whether surgical experience is required

to achieve optimum proficiency in CRE resection surgery.

The 6 surgeons in this study major in gastrointestinal surgery, and 2 were in the high-experience group (R40 cases).

This study shows that patients whose surgeons had performed over 40 operations had a risk of overall complication .26 times and a risk of major complications .30

times, lower than patients whose surgeon’s experience did

not exceed this threshold. Therefore, surgeons who have

745

limited experience in ileal or ileocecal resection for CRE

must carefully select their patients through thorough preoperative evaluation and should give more attention to the occurrence of postoperative complications.

Myelosuppression is a common complication after

chemoradiotherapy, and its influence on surgical outcomes

is largely unknown.25 In the current study, we addressed the

effect of preoperative leukocytopenia and thrombocytopenia as possible risk factors for surgical outcome. Consistent

with the results by Reim et al,26 preoperative clinically unapparent leukocytopenia is not a risk factor for postoperative complications. However, a preoperative platelet count

less than 100 ! 109/L was independently correlated with

major postoperative morbidity. This finding is supported

by previous studies. In a review of 536 patients by Sullivan

et al,27 patients who had undergone recent radiotherapy had

increased complications in emergency surgery, and thrombocytopenia is an independent risk factor for postoperative

death. Patients with complications after pancreatoduodenal

area resection also had significantly lower preoperative

platelet count compared with those without.28 Yang

et al29 also showed that preoperative low platelet count is

an independent risk factor of postoperative morbidity in

major hepatic resection of hepatocellular carcinoma for patients with underlying liver diseases. In another study for

resection of hepatocellular carcinoma, low platelet count

was independently associated with increased major complications.30 Hence, CRE patients with a low platelet count

might benefit from more conservative surgical procedures,

such as bypass or stoma, especially for inexperienced

surgeons.

Literature has shown that ileocecal resection not only

decreased the risk of repeated surgery for CRE but also the

risk of anastomotic leakage.5 Galland and Spencer19 suggested using the ileum and transverse colon for anastomosis

to reduce anastomotic leakage. However, we did not observe a difference of postoperative morbidity between ileocolic and ileoileal anastomosis. Theoretically, the irradiated

bowel has weakened blood supply due to obliterative vasculitis,31 and side-to-side anastomosis can preserve better

blood supply of the anastomosis and therefore decrease

the incidence of anastomotic leakage compared with

end-to-side anastomosis.32 Unfortunately, we did not find

a difference of postoperative morbidity between the 2 anastomotic fashions.

A substantial percentage of CRE patients had more than

1 radiotherapy-associated lesion, commonly ileum with

rectum or ileum with urinary tract. Kimose et al33 found a

combination of radiotherapy injuries affecting the colon,

rectum, small bowel, or the urinary tract in 62% of 182 patients. Turina et al13 demonstrated that two thirds of their

patients developed 2 or more complications from radiotherapy. The incidence rates of colorectal lesions (34 of 158),

radiation proctitis (20 of 158), and radiation uropathy (16

of 158) in the current cohort are 21.5% and 10.1% (both injuries, 9 of 158, 5.7%), respectively. Therefore, we suggest

preoperative colonoscopy or contrast enema examinations

746

The American Journal of Surgery, Vol 206, No 5, November 2013

routinely be performed in patients with CRE obstruction.

Concomitant radiation uropathy may be an indicator of

the severity of radiation injury and the vulnerability of patients to radiation injury, and Chen et al12,34 showed that it

was an independent predictive factor for the need of surgery

and poor overall survival after surgery. Consistent with this,

we also identified it as an independent risk factor for postoperative major morbidity.

Fast track surgery (FCS) has gained wide popularity in

gastrointestinal surgery in recent years.35,36 It aims at reducing surgical stress response, organ dysfunction, and

morbidity, thereby promoting a faster recovery after surgery. Since 2007, a fast track perioperative care protocol

was adopted for our CRE surgery patients, which included

thoracic epidural analgesia, perioperative fluid restriction,37

early ambulance and oral intake, early removal of the gastrointestinal tube, suprapubic urine catheter, and no standard use of abdominal drains. Our results revealed the

FCS did not significantly reduce overall morbidity (P 5

.063), however, it shortens the postoperative hospital stay

(16.6 vs 24.1 days). This indicates that the fast track methodology could be more widely adopted in ileal or ileocecal

resection for CRE.

Conclusions

Our experience has demonstrated that the acceptable

incidence of permanent intestinal failure and surgical

complications justified the application of resection surgery

in CRE with intestinal obstruction. Besides an ASA score

of III or higher and intraoperative transfusion, factors such

as preoperative anemia, thrombocytopenia, inexperienced

surgeons, and presence of radiation uropathy contribute

significantly to postoperative major morbidity. Applying

the principles of fast track surgery in this procedure may

reduce the length of postoperative hospital stay.

References

1. Theis VS, Sripadam R, Ramani V, et al. Chronic radiation enteritis.

Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2010;22:70–83.

2. Birgisson H, Påhlman L, Gunnarsson U, et al. Late adverse effects of

radiation therapy for rectal cancerda systematic overview. Acta Oncol

2007;46:504–16.

3. Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Lockett MA, et al. Radiation therapy morbidity in carcinoma of the uterine cervix: dosimetric and clinical correlation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;44:855–66.

4. Scolapio JS, Ukleja A, Burnes JU, et al. Outcome of patients with radiation enteritis treated with home parenteral nutrition. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:662–6.

5. Regimbeau JM, Panis Y, Gouzi JL, et al. Operative and long term results after surgery for chronic radiation enteritis. Am J Surg 2001;182:

237–42.

6. Iraha S, Ogawa K, Moromizato H, et al. Radiation enterocolitis requiring surgery in patients with gynecological malignancies. Int J Radiat

Oncol Biol Phys 2007;68:1088–93.

7. Onodera H, Nagayama S, Mori A, et al. Reappraisal of surgical treatment for radiation enteritis. World J Surg 2005;29:459–63.

8. Lefevre JH, Amiot A, Joly F, et al. Risk of recurrence after surgery for

chronic radiation enteritis. Br J Surg 2011;98:1792–7.

9. Perin H, Panis Y, Messing B, et al. Aggressive initial surgery for

chronic radiation enteritis: long-term results of resection vs nonresection in 44 consecutive cases. Colorectal Dis 1999;1:162–7.

10. Perrakis N, Athanassiou E, Vamvakopoulou D, et al. Practical approaches to effective management of intestinal radiation injury: benefit

of resectional surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:4013–6.

11. Fearon KC, Voss AC, Hustead DS, et al. Definition of cancer cachexia:

effect of weight loss, reduced food intake, and systemic inflammation

on functional status and prognosis. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:1345–50.

12. Chen MC, Chiang FF, Wang HM, et al. Recurrence of radiation enterocolitis within 1 year is predictive of 5-year mortality in surgical cases

of radiation enterocolitis: our 18-year experience in a single center.

World J Surg 2010;34:2470–6.

13. Turina M, Mulhall AM, Mahid SS, et al. Frequency and surgical management of chronic complications related to pelvic radiation. Arch

Surg 2008;143:46–52.

14. Smit SG, Heyns CF. Management of radiation cystitis. Nat Rev Urol

2010;7:206–14.

15. RTOG/EORTC Late Radiation Morbidity Scoring Schema. Available

at:

http://www.rtog.org/researchassociates/adverseeventreporting/

rtogeortclateradiationmorbidityscoringschema.aspx. Accessed March

12, 2012.

16. Leiper K, Morris AI. Treatment of radiation proctitis. Clin Oncol (R

Coll Radiol) 2007;19:724–9.

17. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients

and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205–13.

18. Boland E, Thompson J, Rochling F, et al. A 25-year experience with

postresection short-bowel syndrome secondary to radiation therapy.

Am J Surg 2010;200:690–3.

19. Galland RB, Spencer J. Surgical management of radiation enteritis.

Surgery 1986;99:133–9.

20. Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and

operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med 2011;364:

2128–37.

21. Gavazzi C, Bhoori S, Lovullo S, et al. Role of home parenteral

nutrition in chronic radiation enteritis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:

374–9.

22. Mundt AJ, Mell LK, Roeske JC. Preliminary analysis of chronic gastrointestinal toxicity in gynecology patients treated with intensitymodulated whole pelvic radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys 2003;56:1354–60.

23. Neumayer LA, Gawande AA, Wang J, et al. Proficiency of surgeons in

inguinal hernia repair: effect of experience and age. Ann Surg 2005;

242:344–8.

24. Kirchhoff P, Dincler S, Buchmann P. A multivariate analysis of

potential risk factors for intra- and postoperative complications in

1316 elective laparoscopic colorectal procedures. Ann Surg 2008;

248:259–65.

25. Sullivan MC, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Does chemotherapy prior to emergency surgery affect patient outcomes? Examination of 1912 patients.

Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:11–8.

26. Reim D, Hüser N, Humberg D, et al. Preoperative clinically inapparent

leucopenia in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced gastric cancer is not a risk factor for surgical or general

postoperative complications. J Surg Oncol 2010;102:321–4.

27. Sullivan MC, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Emergency surgery in patients who

have undergone recent radiotherapy is associated with increased complications and mortality: review of 536 patients. World J Surg 2012;36:

31–8.

28. De˛binska I, Smolinska K, Osiniak J, et al. The possum scoring system and complete blood count in the prediction of complications after pancreato-duodenal area resections. Pol Przegl Chir 2011;83:

10–8.

29. Yang T, Zhang J, Lu JH, et al. Risk factors influencing postoperative

outcomes of major hepatic resection of hepatocellular carcinoma for

N. Li et al.

30.

31.

32.

33.

Ileal/ileocecal resection for CRE

patients with underlying liver diseases. World J Surg 2011;35:

2073–82.

Maithel SK, Kneuertz PJ, Kooby DA, et al. Importance of low preoperative

platelet count in selecting patients for resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Coll Surg 2011;212:638–48.

Galland RB, Spencer J. Natural history and surgical management of

radiation enteritis. Br J Surg 1987;74:742–7.

Resegotti A, Astegiano M, Farina EC, et al. Side-to-side stapled anastomosis strongly reduces anastomotic leak rates in Crohn’s disease surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:464–8.

Kimose HH, Fischer L, Spjeldnaes N, et al. Late radiation injury of the

colon and rectum: surgical management and outcome. Dis Colon Rectum 1989;32:684–9.

747

34. Chen MC, Chiang FF, Hsu TW, et al. Clinical experience in 89 consecutive cases of chronic radiation enterocolitis. J Chin Med Assoc 2011;

74:69–74.

35. Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery. Ann Surg 2008;248:189–98.

36. Vlug MS, Wind J, Hollmann MW, et al. Laparoscopy in combination

with fast track multimodal management is the best perioperative strategy in patients undergoing colonic surgery: a randomized clinical trial

(LAFA-study). Ann Surg 2011;254:868–75.

37. Wenkui Y, Ning L, Jianfeng G, et al. Restricted peri-operative fluid administration adjusted by serum lactate level improved outcome after

major elective surgery for gastrointestinal malignancy. Surgery 2010;

147:542–52.