Title Sign language and the moral government of deafness in

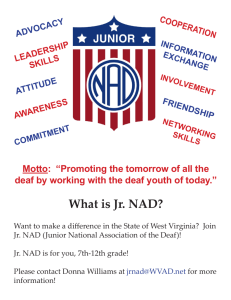

advertisement