The Jewish Bill of Divorce – from Massada Onwards

advertisement

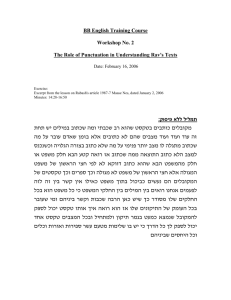

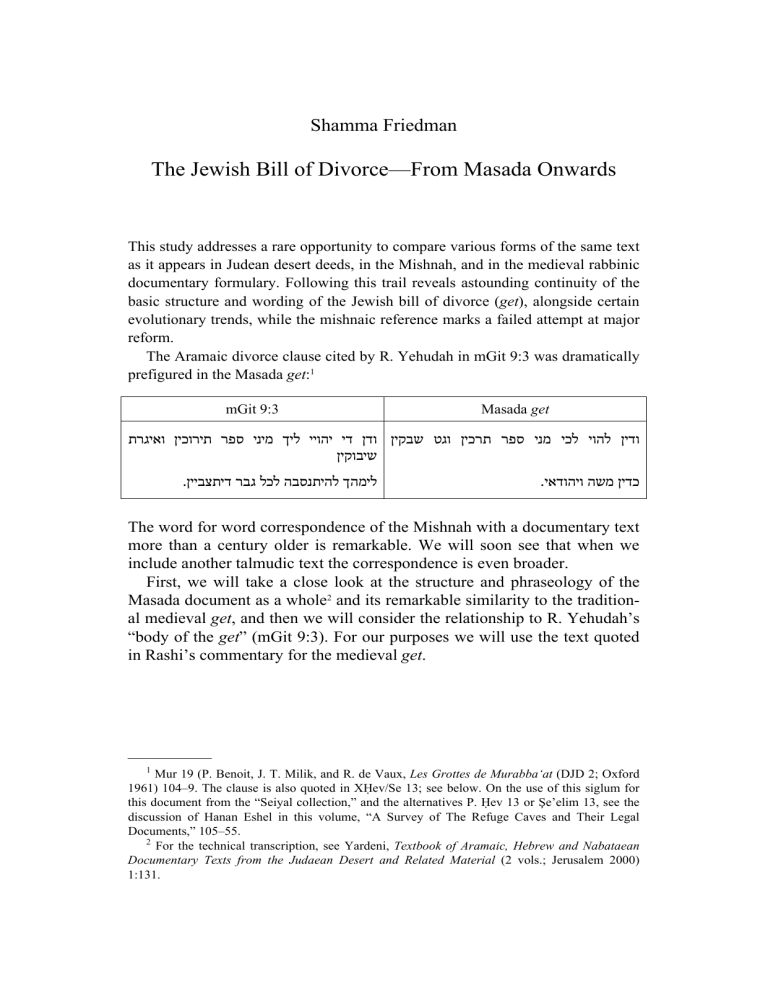

Shamma Friedman The Jewish Bill of Divorce—From Masada Onwards This study addresses a rare opportunity to compare various forms of the same text as it appears in Judean desert deeds, in the Mishnah, and in the medieval rabbinic documentary formulary. Following this trail reveals astounding continuity of the basic structure and wording of the Jewish bill of divorce (get), alongside certain evolutionary trends, while the mishnaic reference marks a failed attempt at major reform. The Aramaic divorce clause cited by R. Yehudah in mGit 9:3 was dramatically prefigured in the Masada get:1 mGit 9:3 Masada get ודין להוי לכי מני ספר תרכין וגט שבקין ודן די יהויי ליך מיני ספר תירוכין ואיגרת שיבוקין .לימהך להיתנסבה לכל גבר דיתצביין .כדין משה ויהודאי The word for word correspondence of the Mishnah with a documentary text more than a century older is remarkable. We will soon see that when we include another talmudic text the correspondence is even broader. First, we will take a close look at the structure and phraseology of the Masada document as a whole2 and its remarkable similarity to the traditional medieval get, and then we will consider the relationship to R. Yehudah’s “body of the get” (mGit 9:3). For our purposes we will use the text quoted in Rashi’s commentary for the medieval get. ————— 1 Mur 19 (P. Benoit, J. T. Milik, and R. de Vaux, Les Grottes de Murabba‘at (DJD 2; Oxford 1961) 104–9. The clause is also quoted in XHev/Se 13; see below. On the use of this siglum for this document from the “Seiyal collection,” and the alternatives P. Hev 13 or Şe’elim 13, see the discussion of Hanan Eshel in this volume, “A Survey of The Refuge Caves and Their Legal Documents,” 105–55. 2 For the technical transcription, see Yardeni, Textbook of Aramaic, Hebrew and Nabataean Documentary Texts from the Judaean Desert and Related Material (2 vols.; Jerusalem 2000) 1:131. 176 mGit 9:3 Cod Kaufmann4 Shamma Friedman Rashi, bGit 85b3 Masada get זהו טופס הגט פטרית יתיכי ליכי אנת1 באחד למרחשון שנת שת1 במצדא שבק ומתרך מן רעתי פלונית בת פלוני דהוית יומא דנה אנא יהוסף בר נקסן אינתתי מקדמת דנא יתב במצדא לכי אנתי...מן מרים ברת יהונתן מהנבלטא יתבה במצדא די הואת אנתי מן קדם דה TTO5 וכדו פטרית ושבקית ותרוכית ודן די יהו)ו(]י[י ליך מיני ספר תירוכין ]וגט גרושין ו[א)י(גרת יתיכי שיבוקין די תהויין רשאה ושלטאה2a בנפשייכי די את רשיא בנפשכי2a למהך להתנסבא לכל מאן ל)י(מהך להיתנסבה לכל גבר2b למהך ולמהי אנת לכול2b גבר יהודי די תצבין דיתצביין דיתיצבייין ואינש לא ימחי בידייכי מן3a ודין להוי לכי מני ספר3a תרכין וגט שבקין כדין משה יומא דנן ולעלם ויהודאי ודן די יהוי ליכי מינאי גט3b כול חריבין ונזקן לכי כדין3b יהיה קים ומשלם לרבען פטורין וספר תירוכין ואגרת .שבוקין כדת משה וישראל ובזמן די תמרין לי אחלף3c לכי שטרא כדי חזא ————— 3 An English translation of the modern get reads: “On the # day of the week, the # day of the month of x in the year # from the creation of the world according to the calendar reckoning by we are accustomed to count here, in the city x which is located on the river x and situated near wells of water, I, pn, the son of pn, who today am present in the city x which is located on the river x and situated near wells of water, do willingly consent, being under no restraint, to release, to set free and put aside you, my wife pn daughter of pn, who are today in the city of x, which is located on the river x, and situated near wells of water, who has been my wife from before. Thus do I set free, release you, and put you aside, in order that you may have permission and the authority over yourself to go and marry any man you may desire. No person may hinder you from this day onward, and you are permitted to every man. This shall be for you from me a bill of dismissal, a letter of release, and a document of freedom, in accordance with the law of Moses and Israel.” 4 “Let this be from me your writ of divorce and letter of dismissal and deed of liberation, that you may marry whatsoever man you wish” (translation adapted from H. Danby, The Mishnah [London 1967]). 5 TTO = transition to operative clause (see below). The Jewish Bill of Divorce—From Masada Onwards 177 The Masada get was translated into English by Yardeni as follows (I have adapted the paragraph division and numbering to the form I will use in my analysis), with some changes: 1 On the first of Marheshwan, year six, in Masada, of [my] own free will, this day, I, Yehosef son of >N Yehosef son of< Nqsn, from ..., residing in Masada, dismiss and divorce you, my wife, Miriam daughter of Yehonathan[ from ]hn/rb/klt’, residing in Masada, who has been my wife before this, 2 (so) that you are allowed to go by yourself and be the wife of any Jewish man whom you desire. 3a And this shall be for you from me a document of divorce and a bill of dismissal according to the law of[ Mos]es and the Jews. 3b All... and damages and ...[...]... to/for you according to the law will be established and paid in quarterly rates (?). 3c And at (any) t[ime ]that you will tell me I shall exchange for you the deed as it is fitting.6 I suggest the following division and function of the paragraphs: 1. Date, place, introduction of principals, and definition of the transaction.7 2. Central operative clause. 3a. “And this” ()ודין. See below. 3b. Compensation for damage 3c. Husband’s commitment to provide a new document upon request. Paragraph 1: Introductory Clause As to 1–3a, the correspondence to the medieval rabbinic get is often astounding. Paragraph 1 corresponds in general to what is called in mGit 3:2 “the (place) for the man’s name, the woman’s name, and the date.”8 This paragraph, both in the Masada get (=M) and rabbinic get (=R), concludes with the identical language: “who has been my wife from before this.”9 This reference to past time is complemented in M by the earlier indication that the action takes place יומא דנה, “this day.” Both phrases appear in a short ————— 6 Yardeni, Textbook 2:57. Corresponding to the first three parts of Yaron’s schema of Elaphantine documents (except “definition of the transaction,” which does not appear there). See pp. 33–37 in R. Yaron, “The Schema of the Aramaic Legal Documents,” JSS 2 (1957) 33–61. 8 Regarding the opinion that this clause is to be identified with the section called תורף, see my study, “תורף,” in S. Friedman, Talmudic Language and Terminology (Jerusalem, forthcoming). 9 M: ;די הואת אנתי מן קדם דהR: דהוית אינתתי מקדמת דנא. Cf. below: די הוית בעלה )= בעלי( מן קדמת דנןin XHev/Se 13. 7 178 Shamma Friedman (partial?) formula for a get cited in bGit 85b as an enactment by Rav,10 however, in reverse order, and with “this day” not indicating present time, but the starting point of future time, “from this day and for all time.”11 In R on the other hand, “from this day and for all time” is attached to a warranty clause (3a) which follows the operative section of the get, no longer indicating that the marital tie is severed for eternity, but guaranteeing that no one can ever challenge [her status as a divorcee].12 bGit 85b Cod. Leningrad13 דאתקין רב בגיטי 'איך פלו' בר פלו Masada get באחד למרחשון שנת שת במצדא שבק ומתרך מן רעתי יומא דנה אנא יהוסף בר פטר ותריך יתב במצדא לכי... נקסן מן מן 'אנתי מרים ברת יהונתן מהנבלטא יתבה ית פלנית בת פלו במצדא דהות איתתיה מן קדמת דנא די הואת אנתי מן קדם דה מיומא דנא ולעלם Paragraph 2: Central Operative Clause In M, 1 and 2 are connected syntactically: ‘ דיthat’ (functional equivalent of - שor )אשרserves to bridge between the introductory clause and the operative clause. We can define these as two clauses in terms of modern conceptualization, but we must admit that in this ancient document the syntactical ————— 10 On the determination that this is the original reading, see my Talmud Ha-Igud Gittin IX (Jerusalem, forthcoming), ad loc. 11 מיומא דנא ולעלםOn the cultural history of this phrase see my study on עולםin Friedman, Terminology. 12 Thus “from this day and for all time” modifies “( לא ימחיshall not protest”). It can be argued that it modifies the entire procedure, therefore פטרית, or that ואינש לא ימחי בידייכיis parenthetical. However, these would yield awkward and unnatural style. Furthermore, the entire idea of someone protesting seems to be borrowed from guarantee clauses in sales transactions, and an anticipation of challenge of the sale by the seller (where מן שמיis often added) or his heirs. “From this day and for all time” is already associated with guarantee clauses in a bill of sale from the Judean Desert, 134 CE (XHev/Se 8; Yardeni, 1, p. 67). The issue is discussed in detail in my Talmud Ha-Igud, Gittin IX, sugya 8. 13 “Rav laid down the formula of the get thus: ‘[We are witnesses] how So-and-so son of Soand-so dismissed and divorced So-and-so daughter of So-and-so who had been his wife before now, from this day and for all time’” (translation adapted from I. Epstein, Soncino Talmud (London 1948). The Jewish Bill of Divorce—From Masada Onwards 179 juncture is predicated on using the verbs “dismiss and divorce” as the operative verbs of the action itself, and not merely naming the action.14 Thus it would be better to translate: “[hereby] dismiss and divorce”). However, in the rabbinic get the two clauses are clearly separated. The separation actually appears to be a conscious rewriting of an inherited formula similar to the one which appears in M. The verbs in 1 are no longer taken as operative, but only as defining the action to follow. This leads to a repetition of these very same verbs in 2: “I divorce and dismiss you.” The very repetition could serve as a marker of secondary composition, even if we did not possess an older exemplar in which they are lacking! The repetition is accomplished by adding a new sub-clause, TTO15, opening with וכדו = “And now”, preceding the original דיof 2b. At this point וכדוmarks the transition from preamble to body, like the modern: (Whereas…[=1]), now therefore [= 2]. The clause TTO beginning וכדוwas already known by the Babylonian Talmud, but only the first word is mentioned there, in a series of cautionary exhortation to scribes of gittin: “The waw of כדוshould also be lengthened so as not to read כדיwhich means ‘in vain.’” (bGit 85b).16 In sources from the geonic period the entire rabbinic get formula, including this clause, is preserved. The language of the operative clause 2b is practically identical in Masada, the Mishnah and the medieval rabbinic get: לימהך להיתנסבה לכל גבר דיתצביין. It is part of the ancient common Aramaic formulary, as found in Elephantine in the 5th century BCE “and she shall go whither she wishes” ()ותהך לה אן זי צבית.17 In style 2b is closer to the Elephantine text than to the biblical and ANE parallels. However, in contrast with the Elephantine formula, the Judean and mishnaic texts make explicit the fact that permission is given specifically to marry,18 and the Masada get further specifies, to marry a Jew. Both issues are discussed in the Talmudic literature.19 In presenting 2a and 2b as an integrated unit, Masada and the rabbinic get are absolutely identical. However, in the Mishnah sub-clause 2a does not appear, and 2b is integrated in a different context (see below). ————— 14 Yardeni’s translation “dismissing and divorcing”, although awkward in English, provides a faithful translation of the original, by using a present participle for the Aramaic שבק ומתרך, participles which, as in Hebrew, are technically nouns, but came to serve as present tense verbs. 15 See supra n. 4. 16 ( וליארכיה לו"ו דוכדו דמשמ' וכדיCod. St. Petersburg - RNL Evr. I 187). 17 B. Porten and A. Yardeni, Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2 (Jerusalem 1989), B2.6 (pp. 30–33); cf. B3.8 (pp. 78–83). 18 In the Mishnah and R most explicit, “to be married” ( ;)להתנסבאM: ל... = למהיliterally “to be to,” with the force of to “be the wife of.” 19 See Friedman, Talmud Arukh, sugya 6. 180 Shamma Friedman Paragraph 3: Closing Clauses M 3b, 3c are standard warranty clauses appearing in many types of Judean Desert contracts and do not have any specific connection to divorce. They do not appear in the rabbinic get, which, interestingly, introduces its own warranty clause, common to other transactions in the rabbinic formulary, but absent in the Masada get.20 Clause 3a in the rabbinic get is a standard warranty provision not specifically related to divorce, and in fact a direct borrowing from sales or gift formulae. Thus it functionally parallels Masada 3b–3c as added standard closing clauses, neither being integral to a bill of divorce. Thus, both M and R have independently added separate warranty clauses to the common base material. Discount these, and their similarity is all the more striking. R 3b. ... ודיןis clearly a schlussklausel. In Masada (M 3a) ... ודיןcontains what was to become the quintessential schlusslkausel “according to the law of Moses and the Jews” ()כדין משה ויהודאי, the elegant marker of a document’s conclusion.21 In the traditional get ודיןappears even after the auxiliary warranty clause R 3a. In other words, R 3a was incorporated to precede ודיןin order to allow ודיןto remain in its original final position. M did not take the trouble to preserve ודיןat the end of the document, and simply added the two warranty clauses after it. A century after the Masada get, R. Yehudah uses the same ancient text, but reworks it at the same time. In the Masada get (and R) ודיןis clearly what the Greeks call a ὑπογραφή or subscription, speaking about the document from the outside, and pointing to it (“and this…”).22 R. Yehudah sought to convert the ὑπογραφή into an operative clause by moving it forward and attaching it to the explicit permission to remarry in 2a, the original operative clause. Thus he reversed 2b and 3a as they appear in the Masada get (eliminating of course, the signatory “according to the law of Moses and the Jews”). ————— 20 As to the relative placing of the clauses in the two documents, see below in detail. See M. Kister, “‘’כדת משה ויהודאי: The History of a Legal Religious Formula,” in D. Boyarin et al, eds., Atara L’haim: Studies in the Talmud and Medieval Rabbinic Literature in Honor of Professor Haim Zalman Dimitrovski (Hebrew; Jerusalem 2000) 202–8; Friedman, Terminology, chapter 14, on the development of this phrase. 22 Falk postulated that this language was originally and oral declaration that accompanied the serving of the get. There is little specific support for this conjecture, as the language and rhetoric is the formal Aramaic of the documentary tradition, and the placing and function correspond to the ὑπογραφή, see below. 21 The Jewish Bill of Divorce—From Masada Onwards Mishnah 181 Masada למהך ולמהי אנת לכול גבר יהודי די תצבין ודין להוי לכי מני ספר תרכין וגט שבקין כדין ודן די יהו)ו(]י[י ליך מיני ספר תירוכין ]וגט משה ויהודאי גרושין ו[א)י(גרת שיבוקין ל)י(מהך להיתנסבה לכל גבר דיתצביין By introducing ... ודיןinto the operative clause,23 R. Yehudah makes it literally “the body of the get” ()גופו של גט, as it is called in the Mishnah. This serves to emphasize, in the body of the get itself, the document’s fulfillment of Deut 24:1 “let him write her a bill of divorcement, and give it in her hand” (יתת וְ נָ ַתן ְבּיָ ָדהּ ֻ )וְ ָכ ַתב ָלהּ ֵס ֶפר ְכּ ִר. The connection with Deut 24:1 is certainly already alluded to in M, with ספר תרכין וגט שבקיןbeing Aramaic translations of יתת ֻ ס ֶפר ְכּ ִר. ֵ 24 In M however, the allusion remains in the schlussklausel, probably a Jewish addition to a traditional divorce document borrowed from an ancient common Aramaic formulary. R. Yehudah’s enactment thus continues this effort by making the main Jewish connection, an allusion to a verse in the Torah, part of the central “body” of the get. As far as we can tell, R Yehudah’s enactment, being a variation of the ancient text, never became operative, neither before or after. His reform failed to displace the standard Aramaic formulary, which remains in medieval gittin (and modern, for that matter), quite within the Masada style. Finally, one further point. In other studies we have suggested that a rabbinic schlussklausel of the ὑπογραφή type constitutes the executor’s assuming obligation to the transaction.25 Thus, while being a closing formula, it has crucial legal importance.26 It is thus understandable why it is this summation clause that is quoted in XHev/Se 13,27 a “divorce quittance, acknowledgment by the wife that her former husband is not indebted to her,”28 for whose reading and reconstruction I propose: ————— 23 Of course one can consider the possibility that reversing the order enabled the newly combined clause to serve as a miniature get in its own right, with R. Yehudah still viewing it as a schlussklausel. This would have his statement in its original form not addressing the “body” of the get at all. 24 And compare the extant Aramaic targumim, suggested by many when dealing with the language of the Mishnah. These issues are dealt with more extensively in Friedman, Talmud Ha-Igud to mGit 9 3. 25 “תורף,” in Friedman, Terminology; idem, “What is Qiyyum (Tosefta Bava Batra 1:4)?” in S. E. Fassberg and A. Mann, eds., Language Studies 11–12: Avi Hurvitz Festschrift (Hebrew; Jerusalem 2008), 269–81 (English summary, XXII–XXIII). 26 I also entertain the idea that this is what is meant by the talmudic term toref ()תורף. 27 Yardeni, Textbook 1:134. 28 J. C. Greenfield, “The Texts from Nahal Şe’elim (Wadi Seiyal),” in Julio Trebolle Barrera and Luis Vegas Montaner, eds., The Madrid Qumran Congress; Proceedings of the International 182 Shamma Friedman [ד]אמרת דין [ הוא לך מנה גט שבקין ותרכי]ין = that you have [said ‘this] is to you from me a bill of divorce and release…’.29 Summary The possibility of comparing three forms of a documentary text across a wide chronological range is a rare opportunity, and in a case such as this— language which appears in Judean desert deeds, in the Mishnah, and in the medieval rabbinic documentary formulary—perhaps unique. Among our findings: 1. The Aramaic “body of the get” cited in the Mishnah in Rabbi Yehudah’s name reverses the order of practically identical language in the Masada get, in order to convert a subscription into the main operative clause. 2. This attempted reform failed to affect the medieval rabbinic get, which is astoundingly similar to the Masada document in structure and language, establishing an impressive example of culture continuity. 3 Once this similarity is established, the differences can be accounted for by independent changes upon a common base text: the rabbinic doubling of the verbs describing the action in order to clearly separate the introductory ————— Congress on the Dead Sea Scrolls, March 1991 (2 vols; STDJ 11–12; Leiden 1992) 2:661–65; XHev/Se 13 is described on p. 664. 29 Continuing further in the line argued by A. Schremer, “Divorce in Papyrus Şe’elim 13 Once Again: a Reply to Tal Ilan,” HTR 91 (1998) 193–202, at 101–2. Schremer did not reconstruct ודין, preferring a demonstrative ( ֵהיאin place of הוא, ostensibly due to space limitation. The same vocalization should appear in Schremer, “Papyrus Se’elim 13 and the Question of Divorce Initiated by Women in Ancient Jewish Halakhah,” [Hebrew] Zion 63 [1998] 377–390, at 387 n. 25). However, now with Yardeni’s clear drawing available, perhaps even clearer than a photograph, I doubt if it could be argued that the space on the line was insufficient. Furthermore, ֵהאas a demonstrative is unattested in Judean Desert documents. D. I. Brewer (“Jewish Women Divorcing Their Husbands in Early Judaism: The Background to Papyrus Şe’elim 13,” HTR 92 [1999] 349–357, at 351) also supplies דיןfor the missing text ([דנן ד]ין...), which he interprets in line with his theory. (Even in terms of Schremer’s understanding, a full ואמרתmay not be necessary). The above quote in context: אנה שלמצין ברת יהוסף קבשן מן עינגדה עמך אנת אלעזר בר חנני]ה[ די הוית בעלה מן קדמת... [ דנן ד]אמרת דין[ הוא לך מנה גט שבקין ותרכי]ין. This scribe exhibits unorthodox orthography, in that he often uses הfor final [ī], so that the underlined words are equivalent to מני, בעלי,( עין גדיcf. l.11 )וקים עלה. In that this analysis seems convincing philologically, we must comment upon the word לךwhich is the standard spelling for the masculine in these documents. (This occurrence appears with the list of masculine forms in Yardeni, Textbook 2:87), while the feminine is לכי (Yardeni, ibid., 2:88), which would be expected. (Cf. T. Ilan, “The Provocative Approach Once Again: a Response to Adiel Schremer,” HTR 91 [1998] 203–4.). However, what can we demand from a scribe who is most unorthodox in his orthographic representations of final [ī], with spellings like ?עינגדהIf עינגדהis עין גדי, with הfor [ī], could not לךbe לכי, with ø for [ī]? The Jewish Bill of Divorce—From Masada Onwards 183 clause from the operative clause; both documents adding separate guarantee clauses.