Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft

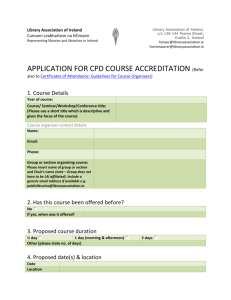

advertisement