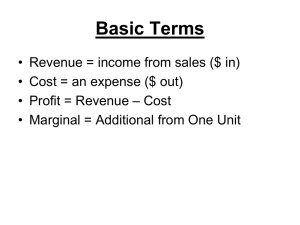

Monopolistic Competition - Learning

advertisement

Monopolistic Competition Between the extremes of pure monopoly and perfect competition there is a range of actual market structures. One type of market in this spectrum is monopolistic competition. Monopolistic competition: a common market structure in which firms have many competitors, but each one sells a slightly different product. As the name indicates, monopolistic competition certain features of both a monopoly and perfect competition. In the early 1930’s economists were concerned about the complete separation of the two existing models of firm and industry behaviour (perfect competition and monopoly), neither of which had many real-world applications. They pointed out that most goods and services are heterogeneous rather than homogeneous, and that many sellers are actually monopolists as far as their own goods and services are concerned. These “monopolists”, however, compete against each other in markets for roughly similar goods. Many firms can thus be regarded as “competing monopolists”, hence the name monopolistic competition. Under monopolistic competition… each firm is small enough (relative to the total market) and the total number of firms large enough so that each firm can ignore the consequences of its actions on the other firms in the market. a large number of firms produce similar but slightly different products. whereas both a monopolist and a perfectly competitive firm produce a homogeneous (standardised, identical) product, monopolistically competitive firms produce heterogeneous (differentiated) products. Product differentiation Product differentiation: the act of making a product that is slightly different to the product of a competing firm. The theory of perfect competition is based on the assumption that all the firms in the particular market produce absolutely identical (or homogeneous) products. When all the products are identical, the only form of competition in which firms can engage is price competition. A pure monopoly can also only exist if the product is unique. If there are close substitutes for the product of a firm, that firm cannot be a monopolist, since it then has to compete against the firms producing close substitutes for its product. Most products, however, are not regarded as absolutely identical by all consumers. When there are different varieties of a product, the product is called a differentiated (or heterogeneous) product. In some cases different varieties of a product are technically different. The contents of two different painkillers may differ. However, the decision as to whether a product is homogeneous or heterogeneous ultimately rests with the consumers. © Bishops Economics Department Page 1 Some consumers regard products as identical and purchase the cheapest one. Others, however, prefer the well-known brands and are therefore willing to pay a higher price to obtain them. Petrol is another example of a good which can be regarded as homogeneous or heterogeneous, depending on consumers’ tastes or preferences. In South Africa, the price of petrol is fixed by government and there is thus no price competition. Some motorists believe that petrol is a homogeneous good and are therefore willing to fill up at any convenient service station. Others, however, prefer a certain brand (eg Sasol, Caltex, Shell), and always try to purchase that particular brand. Techniques of product differentiation include: Advertsing Provision of free gifts with purchases Location Research and development As you can see form the petrol example, even in cases where the price of the product is fixed, competition can be fierce. Deliberate product differentiation is a common phenomenon in the modern economy. Each firm wants to differentiate its product from similar products supplied by other firms. The greater the real or perceived differentiation a firm can establish, the less price elastic the demand for its product becomes. Many markets in the economy can be classified as monopolistically competitive. Good examples are the markets for different types of clothing. Men’s and women’s clothing manufacturing industries in South Africa are characterised by large numbers of firms and low levels of economic concentration. Each monopolistically competitive firm has a certain degree of monopoly power, as it is the only producer of the particular brand or variety of the product. Under monopolistic competition, each firm is thus in effect a mini-monopoly. But, in contrast to pure monopoly, monopolistically competitive firms compete with each other and new firms are free to enter the market for the differentiated product (eg shoes or shirts). Difference Between Monopoly and Monopolistic Competition The essential difference between monopolistic competition and monopoly lies in the barriers to entry. Whereas entry is not restricted under monopolistic competition, it is completely blocked in the case of monopoly. Difference Between Perfect Competition and Monopolistic Competition The essential difference between monopolistic competition and perfect competition is found in the nature of the product. Whereas monopolistic competitors produce differentiated (heterogeneous) products, perfectly competitive firms produce identical (homogeneous) products. Under monopolistic competition, each firm has its own identity. Each firm produces its own variety of a differentiated product and therefore faces a specific downward-sloping demand curve for its product, unlike in a perfectly competitive market where each firm faces a horizontal (perfectly elastic) demand curve © Bishops Economics Department Page 2 For example, the manufacturer of Pierre Cardin shirts faces a demand for Pierre Cardin shirts, rather than for shirts in general. If the price of Pierre Cardin shirts increases, consumers will, ceteris paribus, tend to switch to other brand names (eg Cambridge, Polo, Van Heusen), but the quantity of Pierre Cardin shirts demanded from the manufacturer will not fall to zero, as it would under perfect competition. The equilibrium of the firm under monopolistic competition In a monopolistically competitive market, there are a range of similar products and a range of prices making it difficult to formulate general theories of the behaviour of firms. Nevertheless, we can still analyse the equilibrium of a representative firm under monopolistic competition, in both the short run and the long run. The short-run equilibrium of a monopolistically competitive firm is illustrated in Figure 13-5(a). Like a monopolist, the monopolistically competitive firm faces a downward-sloping demand curve (D) for its product, which is also its average revenue (AR) curve. The only difference with the monopolist is that the price elasticity of demand is larger, since there are many close substitutes for the product of the firm. The firm’s marginal revenue curve (MR) is also downward-sloping and intersects halfway between the price axis and the demand (or average revenue) curve. Profit is maximised at the quantity where marginal revenue (MR) is equal to marginal cost (MC). The short-run profit-maximising quantity is thus Q1, for which the monopolistic competitor charges a price per unit of P1. The economic profit per unit of production is the difference between average revenue (AR) and average cost (AC) at Q1. The firm’s total economic profit is indicated by the shaded rectangle in the figure. © Bishops Economics Department Page 3 This short-run equilibrium cannot be sustained in the long run. The economic profit attracts new entrants and as new firms enter the industry, two things happen. 1. The demand for the product of the original firm falls. Graphically, this is illustrated by a leftward shift of the firm’s demand curve (and a corresponding leftward shift of the firm’s marginal revenue curve). 2. Second, the demand curve for the product of the firm also becomes more price elastic, since there are now more close substitutes for the firm’s product than before. This process will continue until all the economic profits have been eliminated and there is no further entry into the industry. The long run equilibrium of the monopolistically competitive firm is illustrated in Figure 13-5(b). The only possible equilibrium in the long run is where the individual firm produces a quantity (Qe) at which average revenue (AR) = average cost (AC) (ie where economic profit is zero and only normal profit is earned). Graphically, this is indicated by a position where MR = MC and AR = AC. This implies that the AR curve must be at a tangent to the AC curve. In this respect the long-run profit position of the firm operating in a monopolistically competitive market is the same as that of a firm operating under conditions of perfect competition. © Bishops Economics Department Page 4