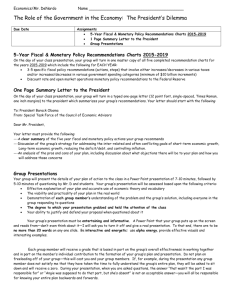

EVERYMAN'S DEFICIT: Spending Beyond Our

advertisement