1 Nominal, Real and PPP GDP It is crucial in economics to

advertisement

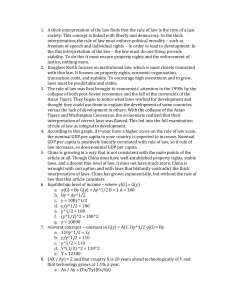

Nominal, Real and PPP GDP It is crucial in economics to distinguish nominal and real values. This is also the case for GDP. While nominal GDP is easier to understand, real GDP is more important and used widely, not least for calculating the growth rate of an economy and comparing the economies of different countries. It is therefore important to understand how real GDP is calculated and how it is related to nominal GDP. As an example, let us suppose that one country, say the United States, produces three final products: Food, Cloth and Automobiles. Table 1 illustrates how this hypothetical country’s nominal and real GDP are derived. In the top two sections, the price and quantity of each good produced in 2010 and 2011 are provided. With this information in hand, it is straightforward to calculate nominal GDP in 2010 (15,600 dollars) and 2011 (21,600 dollars). Table 1 Calculation of Nominal and Real GDP Price (2010) Food Cloth Automobile Total Quantity (2010) 50 80 60 - 100 80 70 Quantity (2011) 80 80 80 - 7,200 8,000 6,400 21,600 Quantity (2011) 50 80 60 - Value 90 100 80 2010 Nominal GDP Real GDP GDP Deflator Value 90 100 80 Price (2010) Food Cloth Automobile Total 5,000 6,400 4,200 15,600 Price (2011) Food Cloth Automobile Total Value 2011 15,600 15,600 1.00 21,600 17,300 1.25 4,500 8,000 4,800 17,300 Rate of change (%) 38.5 10.9 24.9 We choose 2010 as the base year for calculating real GDP. The third section of Table 1 multiplies the price of each good in 2010 by the volume of its sales in 2011. Values in the rightmost column are the revenues that producers of each good would have earned in 2011 1 had its price remained unchanged since 2010. The sum of these values, 17,300 dollars, is called the real GDP for 2011 measured in 2010 dollars, or the real GDP for 2011 with the base year 2010. As should be clear from this explanation, real GDP is nominal GDP that is adjusted for price changes and tells us how much the volume of a country’s production has changed since the base year. Lastly, the bottom part of Table 1 calculates GDP deflators. The GDP deflator is defined as the ratio of nominal GDP to real GDP and tells us how much the country’s general price level has changed since the base year. In our example its value for 2011 is 1.249, suggesting that the average price of goods has risen by 24.9 percent between 2010 and 2011. Now let us assign the following notations to the values derived in Table 1. 2010 V* Nominal GDP * Real GDP GDP deflator V * Y (= V ) General price level Y * P * 2011 P * * S (= P /P = 1) S (= P / P*) With these notations, the definition of the GDP deflator for 2011 can be written as S V , Y (1) which is equivalent to the following relationship: V Y S. (2) When one variable is a multiple of another two variables, its rate of change is roughly equal to the sum of the rates of change in the other two variables.1 Therefore (2) implies % change in V % change in Y % change in S, (3) or Nominal econnomic Real economic inflation rate . growth rate growth rate (4) 1 It should be noted that this relationship holds only approximately. In Table 1, the sum of the rates of change in Y and S is 35.8% while that in V is 38.5%. However, this approximation is fairly accurate when the rates of change in Y and S are less than several percentage points. 2 Figure 1 Growth Rates of the US and Japanese Economies (a) United States 14 (%) GDP deflator 12 Real GDP 10 Nominal GDP 8 6 4 2 0 -4 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 -2 -6 -8 (b) Japan 14 (%) GDP deflator 12 Real GDP 10 Nominal GDP 8 6 4 2 0 -4 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 -2 -6 -8 (Source) IMF, International Financial Statistics. Figure 1 plots the three variables in (3) for the United States and Japan. In both countries, the growth rate of real GDP exhibits cyclical fluctuations each lasting for a few to several years. In Japan, moreover, the average growth rate fell noticeably in the early 1990s, with several 3 years of negative growth since then. While the inflation rate measured by the GDP deflator has always been positive in the United States, Japan has also been suffering from mild deflation since the middle of the 1990s. The method of Table 1 can be applied not only to different years in the same country but also to different countries in the same year. As an example, Table 2 provides hypothetical information on the prices and quantities of goods produced in the United States and Japan in 2010. The top section is identical to that of Table 1 and computes the United States’ nominal GDP. The second section calculates Japan’s nominal GDP in the same year, which turns out to be 2,160,000 yen. Table 2 Calculation of the PPP GDP and the PPP Exchange Rate Dollar price (USA) Food Cloth Automobile Total Food Cloth Automobile Total Quantity (USA) 50 80 60 Yen price (Japan) 8,000 8,000 8,000 - Quantity (Japan) 90 100 80 Quantity (Japan) 50 80 60 - 90 100 80 - USA Nominal GDP PPP GDP in dollars PPP exchange rate 5,000 6,400 4,200 15,600 - Dollar price (USA) Food Cloth Automobile Total Dollar value 100 80 70 15,600 15,600 1.00 Yen value 720,000 800,000 640,000 2,160,000 Value 4,500 8,000 4,800 17,300 Japan 2,160,000 17,300 124.86 The third section computes Japan’s GDP using the dollar prices in the United States, in parallel with what is done in the corresponding part of Table 1. The result of this calculation, 17,300 dollars, is called Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) GDP. The bottom section conducts the same calculation as that of Table 1. Here we divide Nominal GDP not by real GDP but by PPP GDP, and call the resulting value the PPP exchange rate. 4 What do the PPP GDP and the PPP exchange rate represent? To answer this question, let us first give each value in Table 2 the same notation as that of the corresponding value in Table 1. Here we call the United States as the base or reference country, just as we took 2010 as the base year in Table 1. USA Nominal GDP PPP GDP * V * Japan V * Y (= V ) Y * Price level P P PPP exchange rate S* (= P*/P* = 1) S (= P / P*) Given its definition, Japan’s PPP GDP denotes the nominal GDP that the country would have generated if the price of each good had been the same as in the United States. Then it follows that Japan’s (the yen’s) PPP exchange rate, S, represents the ratio of Japan’ general price level to that of the United States, just as S in Table 1 was the ratio of the price level in 2011 to that in 2010. Notice, however, that P and P* are now measured in different currencies. Let us suppose that we are interested in the relative volume of output in Japan and the United States. Since V* and V are measured in different currencies, these values are not directly comparable. If the market exchange rate in 2010 is 1 dollar = E yen, V / E represents Japan’s nominal GDP in dollars. Then one may be tempted to compare V * and V . E (5) This comparison is not appropriate, however. Just as real rather than nominal GDP should be used when calculating the growth rate of an economy, PPP GDP, not nominal GDP, is the right yardstick with which to assess the relative size of two or more economies. Given the above notations, the comparison between Y* and Y is identical to V* V and , * S S (6) which is also equivalent to the comparison between V * and V . P / P* (7) By looking at (5) and (7), we notice that these two comparisons are equivalent only when E P / P* . Although this relationship rarely holds in practice (see below), the PPP exchange rate is precisely the exchange rate that does satisfy this relationship: 5 S P . P* (8) Why S is called the PPP exchange rate can be understood by rewriting (8) as S P* (9) P Japan's price in Yen US price in Yen or P* US price in $ P S . (10) Japan's price in $ These equations tell us that S represents the exchange rate at which the price levels of Japan and the United States coincide with each other, that is, the exchange rate at which one dollar and the equivalent amount of yen have the same purchasing power. In Table 2, S = 124.86. When the actual exchange rate is lower than this value (e.g., E = 100), Japan’s price level is higher than in the United States. It also implies that using (5) instead of (7) would overstate the relative size of the Japanese economy to the US economy. Now let R stand for the ratio of the actual exchange rate to the PPP exchange rate. This value is the real exchange rate, one of the most important variables in international finance. R can be expressed alternatively as R E E E P* P* , S P / P* P P/E (11) which states that the real exchange rate is merely the relative price levels of the two countries. Figure 2 plots the real exchange rate of the domestic currency against PPP GDP per capita (PPP GDP divided by population) for a large number of countries. Since the base country is the United States, the real exchange rate of the dollar is 1 by definition. The real exchange rates of most other currencies are larger than 1, suggesting that the price levels of these countries are lower than that of the United States. It is also evident that the real exchange rate is associated negatively with per capita GDP, implying that the price level tends to rise as a country becomes more affluent. Why this is the case will be analyzed when we study international finance more closely. 6 Figure 2 Real Exchange Rates and Income Levels in 2012 3.0 India 2.5 2.0 R China 1.5 1.0 USA Japan 0.5 100 1,000 10,000 100,000 PPP GDP per caputa (2005 dollars) (Source) World Bank, World Development Indictors (http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators). The upper panel of Figure 3 compares nominal GDP and PPP GDP for a sample of countries. Although the United States is the world’s largest economy in terms of both nominal and PPP GDP, China is catching up rapidly, particularly in terms of PPP GDP. The Indian economy also looks much larger in terms of PPP GDP than in nominal GDP, due primarily to its relatively low price level. Lastly, the lower panel of Figure 3 compares the same countries’ nominal and PPP GDP per capita. PPP GDP per capita has much smaller cross-country variation than does nominal GDP per capita, suggesting that the latter exaggerates real income gaps among countries. Japan’s PPP GDP per capita is substantially smaller than its nominal GDP per capita, reflecting the fact that its price level is high even in comparison with other countries at similar income levels. For example, while its nominal GDP is only marginally smaller than that of Singapore, its PPP GDP per capita is less than 60% of that of Singapore. One reason behind Japan’s high prices is its regulations on imports of certain agricultural goods, a topic that will be explored in Chapters 5 and 6. 7 Figure 3 Nominal and PPP GDP in 2012 (a) GDP 18,000 (billion dollars) 16,000 14,000 12,000 10,000 8,000 6,000 Nominal PPP Nominal PPP 4,000 2,000 0 (b) GDP per capita 120 (thousand dollars) 100 80 60 40 20 0 (Source) See Figure 2. 8