What are coral reefs?

advertisement

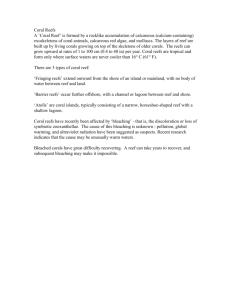

What are coral reefs? Contrary to what many people believe, coral is not a plant but a living organism (polyp) that is part of a unique ecosystem in which it is estimated that a quarter of all marine species can be found. Coral reefs are one of the most productive and diverse communities in the world, which has led to both their appreciation and exploitation. They are known as the ‘rainforests of the oceans’. Coral is made of calcium carbonate (limestone), and builds itself up around the skeleton of dead coral (which is left when a coral polyp dies) in order to increase the size of a reef. Reefs are therefore constructed from millions of tiny coral polyps which live together in colonies. These polyps absorb calcium from sea water to build their limestone skeletons, and when they die these skeletons become what we recognise as a coral reef. There are two types of coral; reef building or hard coral (hermatypic) and non reef-building or soft coral (ahermatypic). Reefs also consist of organisms such as sponges, worms, parrotfish, sea urchins and algae. What are coral polyps? Coral polyps are invertebrates that secrete calcium carbonate to form limestone skeletons, and are the living part of coral. They look like upside down jellyfish, and form a living layer on the surface of skeletons left behind by dead polyps. They belong to the same group as jellyfish and sea anemones, and are around 2-3 cm long. Polyps absorb the calcium in sea water to create the limestone skeletons that form coral reefs when the polyp dies. Coral polyps work in conjunction with a plant, zooxanthellae, in a process called symbiosis which produces energy for the coral to live and reproduce. Zooxanthellae are unicellular algae, and the symbiotic relationship they have with polyps is called so because it is mutually beneficial. The zooxanthellae photosynthesise and share the food and oxygen produced with the coral polyp in return for receiving protection, access to light and carbon dioxide. Source: Coral Cay Conservation http://www.coralcay.org/science/reefs/coral_reef_ecology.php Coral Reef Alliance http://www.coralreefalliance.org/aboutcoralreefs/overview.html US Environmental Protection Agency http://www.epa.gov/cgi-bin/epaprintonly.cgi Coral formations vary widely, from branching trees, large domes and small layers to organ pipe formations. They also vary in colour and shape, depending on variety and environment. Flatter corals tend to form where there are strong waves, whereas branch patterns are more common in sheltered areas. Coral polyps have clear bodies and their skeletons are white. They get their beautiful colour from the algae (zooxanthellae) that live inside their tissue. Credit: J Nortcliffe Fringing reef A fringing reef runs directly along the line of a coast, and extends out from the land into tropical seas. They are commonly found in the South Pacific, Hawaiian Islands and the Caribbean. Barrier reef A barrier reef is separated from a mainland or island by a wide lagoon, and occurs further offshore than a fringing reef. This type of reef forms when land masses sink, allowing fringing reefs to become separated from shorelines by wide channels. Barrier reefs are found in the Caribbean and Indo-Pacific regions. The Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia is the largest barrier reef in the World, and stretches for 1,240 miles. Atoll reef An atoll reef has a circular formation of continuous reef, which surrounds a lagoon without a central island. They usually form when islands surrounded by fringing reefs sink into the sea, or when sea levels rise around them. These islands are often the tops of underwater volcanoes. Atolls occur in the Indo-Pacific, and the largest one in the world surrounds a lagoon that is over 60 miles long. Apron reef An apron reef is similar to a fringing reef but has a gentle slope out and downwards from a point. Patch reef A patch reef is often isolated and circular in shape, usually within a lagoon or bay. They are common in the area between fringing reefs and barrier reefs, and rarely reach the surface of the water. Ribbon reef A ribbon reef is a long and narrow reef, usually associated with an atoll lagoon. Credit: J Nortcliffe Table reef A table reef is similar in shape to an atoll reef, but without the central lagoon. Coral Reef Facts - Taking into consideration the economic value of fisheries, tourism and coastline protection, the cost of destroying 1 km of coral reef is between US$137,000 and US$1,200,000 over a 25 year period. - When managed properly, coral reefs can provide about 15 tonnes of fish and seafood per sq km a year. - More than 80% of the world’s shallow reefs are over-fished. - Coral reefs occupy less than a quarter of 1% of the ocean, but are home to more than 25% of all known fish species. - According to the World Atlas of Coral Reefs published by the UN Environmental Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre, around 58% of the world’s coral reefs are potentially threatened by human activity. - Of the 109 countries that coral reefs are found in, 93 have experienced some kind of coral degradation. - Between 1876 and 1979, 3 coral bleaching incidents were recorded, whereas between 1980 and 1993 60 incidents were recorded. In 2002 more than 400 examples were recorded. - We have already lost 27% of the world’s coral reefs. If this continues at the present rate, 60% of the world’s coral reefs will be lost in the next 30 years. - The economic value of Indonesia’s reefs is estimated at US$1.6 billion annually. - Southeast Asia has 34% of the world’s coral reefs, spread over 100,000 sq km and providing a home to over 600 reef building species. - Indonesia and the Philippines hold nearly 80% of the world’s threatened reefs. - Approximately 8 million coral reef species are estimated to be undiscovered. - Of the 7500 known species of coral approximately 5000 are now extinct. - Approximately 40% of the reefs that were seriously damaged by bleaching in 1998 are either recovering or have recovered. Sources: WWF http://www.panda.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/marine/what_we_do/coral_reefs/ about/Coral_facts.cfm American Association for the Advancement of Science: Moore, Franklin and Best, Barbara ‘Coral reef crisis: Causes and Consequences’, found at http://www.aaas.org/international/africa/coralreefs/ch1.shtml Coral Cay Conservation: http://www.coralcay.org/science/reefs/how_are_reefs_threatened.php http://www.coralcay.org/science/reefs/coral_reef_ecology.php Where are they located and why? Coral reefs are found in all the oceans of the world but are most common between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, mainly because reef-building coral is prevalent in these areas. The main areas in the Western Atlantic Ocean to find reefs are Bermuda, the Bahamas, the Caribbean, Belize, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico. The Indo-Pacific region also has large amounts of reefs, which are located in an area which extends from the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, through the Indian and Pacific Oceans to the western coast of Panama. Reef-building corals are mainly found in shallow water (generally under 50 metres deep but some can survive to 90 metres), where sunlight can reach the ocean floor to provide the corals with the energy they need to grow. This means that growth increases depending on how clear the water is, as less light is absorbed by clearer water. Corals do not photosynthesise, but live with microscopic algae which photosynthesise for them which is why they need sunlight to live. Non reef-building coral has been found in deeper water (up to 6,000 metres deep), where it survives by feeding on the organic matter in the ocean currents rather than through the energy from sunlight. Reefs do not form around the mouths of rivers due to larger than normal amounts of sediment and pollution. Credit: J Nortcliffe Coral reefs need warm water temperatures of between 20-28 ºC (68-82 ºF) in order to grow, and find this warm water along the eastern shores of major land masses. Reef development is more common in areas that experience strong wave action. This is because waves carry food, nutrients and oxygen to the reef, distribute coral larvae and prevent sediment from smothering the reef. The formation of a coral polyp’s skeleton requires the precipitation of calcium in the surrounding water. This precipitation occurs when water temperatures and salinity are high, and carbon dioxide levels are low. These conditions are provided by the warm, shallow tropical waters between 30 degrees N and 30 degrees S latitudes. Why are coral reefs important? The value of a coral reef is generally assessed depending on its economic and ecological value. However, there are other values which are becoming increasingly important as we strive to conserve this fragile ecosystem. Coral reefs are an excellent indicator of environmental change and the ecological quality of an area. Ecosystem / Diversity Coral reefs provide a natural habitat for a wide variety of fish species and other plants and creatures. Reef systems are estimated to be home to around 1 million different species, all of which have adapted to their surroundings to tolerate specific diets, their unique habitat and the threat of reef predators. Grazing fish, sea urchins, sponges and other organisms can be found within the reef ecosystem, all of which help to break down dead coral polyps and build the reef. Coral reefs have around six trophic levels. Coral also influences the Credit: J Nortcliffe amount of carbon dioxide in the oceans, as coral polyps fix carbon dioxide to form limestone. This acts as a ‘carbon sink’ for excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and oceans. Tourism If managed in a sustainable way, tourism can not only provide income for the countries that open their reefs to holiday makers, it can also ensure reefs are protected for generations to come via management schemes, education and awareness. Billions of pounds are spent each year on diving tours, fishing trips, hotels, restaurants and tourist-based business centred around reef areas, all of which create income for a massive number of people. Reefs also contribute to the formation of the sandy beaches we find in these areas via the disintegration of coral over time. Economy According to one estimate, coral reefs provide goods and services worth approximately $375 billion each year, which is amazing when you consider that reefs cover less than 1% of the earth’s surface. The economic benefits of a reef include coastline protection services (protecting coasts from waves and storms etc), places for tourism and recreation, sources of food, medicines and livelihoods. Studies have shown that on average, countries with coral reef industries derive more than half their gross national product from them. Medicine Coral reef has been found to contain a variety of compounds which are useful in medicine. Recent research has linked these compounds to treatments for heart disease, cancer, HIV, arthritis, bacterial infections and viruses. For example, a Caribbean reef sponge provides chemicals which are used in a well known HIV treatment. Coral’s skeletal structure has also been used to make bone grafting material. Coastline protection Coral reefs act as filters for the water around a shoreline, helping to maintain good water quality in the area around the reef. Reefs that are located offshore form barriers, and provide shelter from ocean waves by acting as breakwater. They are also self-building and selfrepairing, thus providing an excellent source of coastal protection in areas that would perhaps not otherwise be able to implement such a scheme. Reefs also protect coastlines from storms and floods, preventing loss of life, property and erosion. They also help to produce the sandy beaches that are popular with tourists, as the debris caused by the breakdown of the reef skeletons is washed ashore. Credit: J Nortcliffe References and Sources American Association for the Advancement of Science Birkeland, Charles ‘Can ecosystem management of coral reefs be achieved?’, found at: American Association for the Advancement of Science http://www.aaas.org/international/africa/coralreefs/ch3.shtml Moore, Franklin and Best, Barbara ‘Coral reef crisis: Causes and Consequences’, found a: American Association for the Advancement of Science http://www.aaas.org/international/africa/coralreefs/ch1.shtml Spruill, Vikki and Dropkin, Lisa, ‘Ocean Attitudes 2001: Conservation through consumer action’, found at: American Association for the Advancement of Science http://www.aaas.org/international/africa/coralreefs/ch5.shtml Bowen, Ann and Pallister, John (2001) ‘A2 Geography’, Heinemann Coral Cay Conservation: http://www.coralcay.org/science/reefs/how_are_reefs_threatened.php http://www.coralcay.org/science/reefs/why_conserve_reefs.php http://www.coralcay.org/science/reefs/coral_reef_ecology.php Coral Reef Alliance http://www.coralreefalliance.org/aboutcoralreefs/overview.html http://www.coralreefalliance.org/aboutcoralreefs/care.html http://www.coralreefalliance.org/aboutcoralreefs/threats.html Digby, Bob (Ed) (2000) ‘Changing Environments’, Heinemann Elcome, David (1999) ‘The Fragile Environment: Pollution and Abuse’, Nelson Thornes Sea World Adventure Parks http://www.seaworld.org/infobooks/coral/deathcr.html http://www.seaworld.org/infobooks/coral/coralcr.htlm http://www.seaworld.org/infobooks/coral/habdiscr.html The International Ecotourism Society http://www.ecotourism.org/index2.php?what-is-ecotourism University of the Virgin Islands http://manta.uvi.edu/coral.reefer/threats.htm US Environmental Protection Agency http://www.epa.gov/cgi-bin/epaprintonly.cgi Warn, S and Naish, M (Eds), 2000 ‘Changing Environments: AS level geography for Edexcel B’, Longman Wikipedia http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/coral_reefs Wilkinson, Clive (Ed) (2004) ‘Status of Coral reefs of the World 2004, Volume 1’, with the Coral reef Monitoring network, Australian Institute of Marine Science WWF http://www.panda.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/marine/what_we_do/coral_reefs/about /Coral_facts.cfm