The Boxer Movement, the Open Door notes and the Formation of

advertisement

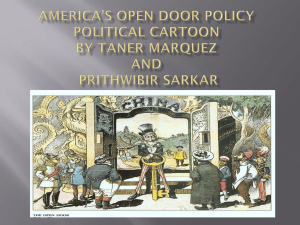

The Boxer Movement, the Open Door notes and the Formation of American Paternalism toward China When the Boxer Movement happened in China around 1900, Herbert Hoover, who later became the 31st American President, was working as a mining engineer in Tianjin. He and his American colleagues witnessed the whole movement. Many years later, one of his colleagues told a story in his memoir: In June 1900, there were a large number of the Boxers in the city of Tianjin where continuing disorder had been reported. One day, Hoover in his neighborhood rescued from a heavy fire a little Chinese girl whose mother had just been killed by a bomb. After resettling the little girl, Hoover returned to the United States. …About twenty years later, when Hoover was Commerce Secretary, He met the couple of Chinese minister to U.S. at a banquet. The wife of the Chinese minister was, according to the writer of the memoir, an “elegant lady who was fluent in English.” She asked Hoover, “Mr. Hoover, do you remember me?” Not recognizing her, Hoover felt a little awkward. Then the lady smiled: “I am the little girl you rescued in Tianjin.”… The authenticity of this story is impossible to examine. However, the story itself implied a metaphor of Sino-American relations: U.S rescued China from chaos and disorder (the little girl represented China who was very week and was in need of help), and helped china grow into a modernized country (the elegant lady represented the civilized China: her manner was consistent with American standard of being civilized). This metaphorical relationship between U.S. and China could be defined as “paternalism”. Paternalism depicts the relationship between self and others as that of parents and children. Taking themselves as parents and others as children has two implications. On one hand, it emphasizes authority and superiority. It is generally known that children are not only physically weak but mentally immature so that they are easy to go astray, whereas parents could provide children with the protection, care and guidance to ensure the children developing in a right way, and punish them if their behaviors were inappropriate. So paternalism legitimates the control and domination of children by parents. On the other hand, paternalism, illustrating a family relations, is different from other kinds of power relationship, as parents always love and care their children, so in this unequal relationship, the parents regard themselves as “kind” and “benevolent.” In the discussion of the American image of China, Warren Cohen defined the period of 1900-1950 as a “paternalistic era.” He pointed out that the U.S began to consider itself to be the protector of China and to serve as the model from whom China should learn after the Open Door notes.1 Besides Warren Cohen, many other scholars hold similar opinions,2 so dose this essay. But the focus of this essay was placed on the formation of the paternalistic attitude toward China. The scholars who studied Sino-American mutual images have agreed that Americans’ attitude toward China was still “contempt” and “exclusion” during the late 19th century, This was followed by a question: Why did paternalism predominate in American perceptions of China after the early 20th century? Historical Events and the Transformation of American Image of China There have been a lot of debates on the American image of China. However, most of them only gave detailed descriptions, throughout the text analysis, of the image of China in the U.S at different periods. These studies generally attributed the transformation of the image to the development of Sino-American relations and the change of mutual interests. In some studies, these materialistic factors were only treated as the background of image transformation.3 1 Warren Cohen, “American Perceptions of China,” in Michael Oksenberg and Robert Oxanam eds., Dragon and Eagle: United States-China Relations: Past and Future, New York: Basic Books, 1973, pp. 54-86. 2 Harold Issacs, in his well-known book Scratches on our minds: American images of China and India, concluded many dimensions of American image of China, among which, one was “wards”. see Harold Issacs, Scratches on our minds: American images of China and India, New York: J. Day Co., 1958; Wang Lixin in his essay “American Perceptions of China, 18th to 1950” defined American perception of China in the first half of 20th century as “sympathy and condescending”, see Wang Lixin, “American Perceptions of China, 18th to 1950,” in World History, Jan., 1998. Although different phrases were used, they have the similar connotation with “paternalism.” 3 Stuart C. Miller , The Unwelcome Immigrant : The American Image of the Chinese , 1785-1882 , Berkeley : University of California Press , 1969 ; Patricia Neils , China Images in the Life and Times of Henry Luce , Savage , MD : Rowman& Littlefield , 1990 ; Patricia Neils , ed. , United States Attitudes and Policies toward China : The Impact of American Missionaries , Armonk , N. Recently, some scholars have noticed that the change of the American image of China was partly resulted from the development of China, but, to a large degree, it was owing to “the American historical process itself,” as the image of others reflected “Americans’ desire and aspiration.” In other words, the American image of China belonged to American culture. According to cultural historians, culture was a process that was not static or fixed. Therefore, the American image of China could be divided into various stages and evolved over time. When studying the image transformation, some scholars examined the development of the national aim and national aspiration of the United States. 4However, some questions remained: how did the change of American aspiration develop into the change of the American image of China? Is this development a slow and cumulative process or a sudden happening? It has been well known that the American image of China has several phases. The change of the image might be caused by a long-term cumulative development, but there were always some “junctures” in history. And these junctures were often the important historical events where the image would experience a significant transformation. Culture was defined and redefined all the time. When an American journal published an essay about China, or an American movie created a Chinese character, the image of China might be more or less revised by this essay or this character. It might reinforce an aspect of the old image of China, or add new elements into the old image. But this kind of revision was often smooth and slow, or even imperceptible. However, when significant events happened, a pronounced development and transformation of culture could occur in a short time, because such events attracted much attention, and stimulated people to explain, comment and give opinions. An event might be caused by many reasons. The contemporary and later comments and interpretations might be inconsistent with the truth of the event, and therefore, Y. : M. E. Sharpe , 1990 ; Jonathan Goldstein , et al. , eds. , America Views China : American Images of China Then and Now , Cranbury , NJ :Associated University Presses , 1991 ; A. Owen Aldridge , The Dragon and the Eagle : The Presence of China in the American Enlightenment , Detroit : Wayne State University Press , 1993 ; T. Christopher Jespersen , American Images of China , 193121949 , Stanford : Stanford University Press , 1996. 4 Wang Lixin, “The Development of American Perceptions of China, 18th to 1950,” in World History, Jan., 1998. resulted in various explanations. However, when people tended to develop the same view on the event, or when one explanation of the event became dominant, this event would be connected to some cultural symbols. These cultural symbols would either consolidate some old cultural concepts, or promote the generation of a new cultural meaning.5 In the history of Sino-American mutual images, the Opium War served as such a “juncture”. According to the image studies, during the first half of 19th century, when there were not many interactions between U.S and China, Americans extolled China as an old and rich country, full of wisdom, and admired Chinese as industrious and kind-hearted people. With the Opium War, however, “a sudden revulsion of feeling took place, and from being respected and admired, China’s utter collapse before the British arms and her unwillingness to receive western intercourse and ideals led to a feeling of contempt.” The impression that China was “decadent, dying, and fallen greatly from her glorious past” spread throughout the United States and Europe.6 At the early 20th century, Americans’ attitude toward China experienced another significant transformation as a result of another historical event---the Boxer Movement. This essay will explores how contemporary Americans’ explanations and comments of the Boxer Movement (including the Open Door notes initiated by U.S. government during that time) helped to develop the American paternalistic attitude toward China. The Boxer Movement and the Image of “Backward” and “Barbaric” Chinese The Boxer Movement, which happened in China in 1900, attached worldwide attention. As foreign legations in Beijing were under siege by the Boxers, western countries send allied armies to suppress the uprising and occupied Beijing and Tianjin for several months. 5 William H. Sewell, Jr., “Historical Events as Transformations of Structures: Inventing Revolution at the Bastille,” Theory and Society, Vol. 23, No. 6 (Dec. 1996). 6 K. S. Latourette, the History of Early Relations Between the United States and China, New Haven, 1917, pp. 124. This uprising shocked Americans who did not know what happened in China and why. Those who stayed in China and witnessed this crisis as well as those who observed China closely in America provided their interpretations on the origins of the Boxer Movement. According to them, the barbarity and backwardness of the Chinese was the main reason for this uprising. As discussed above, Americans’ opinion of the Chinese was unfavorable since the Opium War. Arthur Smith, in his well-known book Chinese Characteristics, listed 26 characteristics of the Chinese. 18 of them were negative.7 Because of the racism popularized in the U.S, those negative characteristics were interpreted as the race qualities of the Chinese. According to the logic of racism, the skin color of human being reflected the degree of their evolutionary development and the level of moral standard. As a yellow race, far behind the white race in the hierarchy of race, Chinese was thought to be barbaric, ignorant and cruel. “The Chinaman is cruel from the cradle.” “To torture animals, to attend and to gloat over executions, and to gaze on human suffering in any form, afford the keenest delight to the Chinese youth.” 8 “Chinese civilization had not reached the point where it could appreciate and recognize the humanity.” 9 “ The Chinese were in a depraved state which was little better than that of the animals.” 10 When the Boxer Movement occurred, Americans with long-standing racial prejudices readily ascribed the anti-foreign uprising to the racial or national character of the Chinese not the activities of some individuals or certain organizations. In a message to the Congress, President McKinley commented on the crisis in China, its “origin lies deep in the character of the Chinese races and in the tradition of their government.” In his following speech, he mentioned words such as “the ignorance and superstition of the masses” and “primitive people” several times. 7 11 The former Arthur Smith, Chinese Characteristics, New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1894. This book was published in 1894 and greatly influenced Americans’ image of China. 8 “Chinese Cruelty,” Harpers Weekly, Feb. 23, 1895, p. 182. 9 “Editorial”, Harpers Weekly, Jan. 12, 1895, p. 31. 10 “Editorial: Religion and Poverty in China,” Missionary Review, Jan., 1895, pp. 141-142. 11 James D. Richardson, “William McKinley to the Senate and House of Representatives,” A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, New York: Bureau of National Literature, 1902, Vol. XIII, P. 6418. United States Vice-Consul General at Hong Kong, Edwin Wildman, held the similar view on the Boxer Movement that he ascribed it to the immorality of the Chinese, “The moral turpitude of the race itself, its ignorance and superstition, its decadent educational institutions and rotten throne, are the vitiating influences that have brought about China’s terrible misfortunes.” 12 Mrs. Hoover, the future first lady, who was trapped in Tianjin with his husband during the Boxer Movement, also described this uprising as a “race war”. 13 In the coverage of the Boxer Movement, the atrocities of the Chinese were repeated. An article in Outlook described the murder of a missionary: “Mr. Brooks …was one night stripped naked and his ears and nose sliced off; after the Boxers had finished celebrating this event by a supper, he was killed.”14Two days later, Chicago Daily Tribune reported the details of Murder at Pao Ting Fu. 15 And an account in North American Review described the murder of a Belgian priest with the heart-sickening details.16 As this poor man hung from the tree to which he was tied, pieces were cut from his thighs and eaten by his tormentors….Finally his body was cut open, from the chest to the bottom of the abdomen; he was disemboweled, and the various organs were taken out and eaten by these semi-civilized people, who at the same time drank his blood. He was also mutilated in a way that cannot be described, and his head was cut off. After Jun. 1900, when the Boxers entered Beijing and cut off the telegraph and railway between Beijing and Tianjin, the situation in Beijing became unknown to outsiders for the next two months. However, during that time, some rumors appeared in the American press stating that the embassies and missionaries were all massacred. The Independent said, “…after the massacre of the foreigners the Boxers turned upon the native Christians and cut to pieces everybody who would not join them, so that the 12 Edwin Wildman, “The Passing of Li Hung Chang,” Munsey’s Magazine, Aug. 1901, p. 663. “Underlying Causes and Boxers,” Lou Henry Hoover Papers, in Herbert Hoover Presidential Library. 14 “The Chinese Situation,” Outlook, Jun 9, 1900. 15 “The Details of Murder at Pao Ting Fu,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Jun. 11, 1900. 16 Robert Lewis, “The Gathering Storm of China,” North American Review, Aug., 1900. 13 streets of the city were everywhere flowing with blood.” 17 The Boxers may have behaved inappropriately. However, the atrocities described in the press were usually not witnessed by the authors. The words such as “it was heard that,” and “there was report that” were often used before these details. This suggested that the information were second-hand. Therefore, the only possible reason to provide such detailed descriptions for the event was to attract readers’ attention by exaggerating the barbarities of the Chinese. The appearance of the atrocity stories18in the American press was partially due to the yellow journalism19that was popularized at the turn of the 19th century. And the stories could be accepted by the public because they agreed well with the backward, barbaric Chinese stereotype for Americans. Additionally, the above-mentioned report in which all foreigners in Beijing were massacred was soon proved to be a rumor. The emergence of rumors was a result of insufficient information to some extent, however, the extensive popularity of rumors was partially caused by their agreement with the Americans’ long-held prejudice about the Chinese. As an anthropologist said, “Given that such rumors are intrinsically disturbing, passing them may be a way of validating one’s prejudices as much as sharing one’s fear…”20 The coverage of the Boxer movement in the American domestic press reflected the racial prejudice of Americans on the Chinese on one hand; it also reinforced it on the other. The detailed description mentioned above easily impressed the readers that the Chinese were “blood-thirsty” and “ferocious” barbarians. A reader wrote to Boston 17 “The Massacre at Peking,” The Independent, July 19, 1900。 In an essay “Leaving a Brand on China: Missionary Discourse in the Wake of the Boxer Movement,” American scholar James Hevia found out that missionaries often exaggerated the atrocity of the Chinese in their account of their experience in the Boxer movement. Hevia interpreted it as two reasons; (1) missionaries took this crisis as a test of their determination to spread the Christianity, they emphasized their sufferings in order to prove their loyal to God and their willing to spread the gospel; (2)the telling of the atrocity stories of the Chinese was used to justify missionaries’ looting during the occupation of Beijing and Tianjin by the allied army. Hevia’s essay was enlightening and inspired me a lot, but it did not explain why secular press had the similar accounts. See James L. Hevia, “Leaving a Brand on China: Missionary Discourse in the Wake of the Boxer Movement,” in Modern China, Jul. 1992, pp. 304-332. 19 See Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1957. 20 Paul Cohen, History in Three Keys: the Boxers as event, experience, and myth, Columbia University Press, c1997, p. 148. 18 Herald after reading the accounts about the Boxer Movement, “These people are savages….”21 The following cartoon was published during the period of the Boxer Movement. In this cartoon, the Chinese was painted as a barbarian with a pigtail on his head and a bleeding sword in his mouth. He seemed to hijack the whole “earth”. The demonization of the Chinese like this cartoon scared the readers to the extent that, many years later when Harold Isaacs performed investigations for his well-known image study, an interviewee “called up almost at once the sensation of terror aroused by accounts of the Boxer time which he had read as a boy” when talking about China.22 (Cartoon one: World, June 17, 1900.) The Boxer Movement strengthened the long-held image of the Chinese as a barbaric and inferior race. Although the movement was soon suppressed by the allied 21 Boston Herald, July 18, 1900, p. 8. Harold R. Issacs, Scratches on Our Minds: American Images of China and India, New York: The John Day Company, 1958, p.106. 22 army, Americans’ fear did not dissipate. For some Americans, China, with a vest territory, a large population and a very different culture, was more dangerous than other non-western countries, so it was necessary to “educate” and “uplift” the Chinese in order to prevent “another uprising against the civilized world such as this we are now witnessing”23 An article in New York Times pointed out that China needed to be modernized immediately, and declared frankly “whatever injustices may be committed in the course of the modernization of China will evidently be lesser evils than the continuance of the unmodernized China.”24 However, who should take the responsibility of civilizing the Chinese? For many Americans, the United States was considered to be more suitable to assume this responsibility compared to other world Powers. “Open Door” Notes and the Myth of “Protection of China” During the Boxer Movement, eight Powers send allied armies to China in the name of protecting their nationals. China faced a danger of being carved up. The critical situation of China made U.S. government to think about how to deal with China after the Boxer Movement and how to protect American interests in China. In July 3rd, 1900, American government dispatched a circular note to Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, Japan through American embassies in those countries that, “the policy of the Government of the United States is to seek a solution which may bring about permanent safety and peace to China, preserve Chinese territorial and administrative entity, protect all rights guaranteed to friendly powers by treaty and international law, and safeguard for the world the principle of equal and impartial trade with all parts of the Chinese Empire.”25 This was called the second Open Door note. The first Open Door note was issued by the United States several months before the Boxer Movement, which was to protect the equal trading rights in the sphere of influence in China of other world powers. The second Open Door note 23 W. A. P. Martin, The Siege in Peking, New York: Fleming h. Revell, 1900, p. 157. “An Army of Civilization,” New York Times, Jun 20, 1900. 25 Hay circular, July 3, 1900, Foreign Relations of the United States 1901, Appendix: Affairs in China, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902, p. 12. 24 added the words like “preserves Chinese territorial and administrative entity.” These two notes established American policy toward China. The initiation of the two Open Door notes by the U.S government was out of their own interests. In the late 19th century, as the frontier in U.S was closed, more and more American people believed that the long-lasting domestic prosperity increasingly relied on ever-expanding oversea markets. With a large population, China surely served as a big potential market for the United States.. In a letter to their congressman, a group of textile manufactures wrote in 1899, “You can see at once what the importance of the China trade is to us. It is everything.”26 But when Americans became increasingly interested in the boundless China market, China was to be carved up by other Powers. Therefore, the prime aim of the Open Door Notes was to help American businessmen and industrialists obtain the China market. With the words “preserves Chinese territorial and administrative entity” in the second Open Door note, the United States, however, did not plan to “protect” or “rescue” China. Instead, they had plans of acquiring a base on the Chinese coast. During the Boxer Movement, The Army and Navy Journal flatly declared in late June, 1900, that the United States should demand at least one Chinese port, should the outbreak lead to a partition of the empire. 27 Edwin Conger, American minister to China also suggested that the United States take Zhili province as its sphere of influence. 28 , At last, the U.S. government initiated Open Door notes instead of acquiring a naval base or a sphere of influence in China. It was owing to the anti-imperialist movement in the U.S. and the Chinese strong resistance to the dismemberment suggested in the Boxer Movement. Although including the phrases “preserves Chinese territorial and administrative entity” in the second Open Door Note, U.S did not provide any guarantee to perform it. That is to say, if other world powers did not 26 Cited by Matthew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: the United States encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917, New York: Hill and Wang, 2000, p. 27. 27 Cited by William R. Braisted, The U. S. Navy in the Pacific, 1897-1909, Austin, 1959, p. 125. 28 Cited by Alfred L. P. Dennis, Adventures of American Diplomacy 1896-1906, New York, E. P. Dutton and Company, 1928, p. 208. agree, the U.S would not have taken any measure to carry it out. The July 3rd circular even did not require any response from the governments to which it was sent. Nor did any, except Great Britain, send a reply of any kind. Thus the Open Door note was only a statement of American policy, announcing its purposes and positions in the question of China, not a concrete guideline. However, as we all know, Chinese territory was indeed preserved after the Open Door notes. Historians have concluded that this was resulted more from the competition among the world Powers than the Open Door Notes. Besides, the Boxer Movement made westerners realize the cost of controlling China. After the uprising, Alfred von Waldersee, the commander-in-chief of allied forces, admitted the difficulties of partitioning China, “No matter it is Europe, America, Japan or any country, they do not have the energy or military power to rule over one-quarter of the population of the world. So it is a bad move to partition China.”29 Nevertheless, the issue of the Open Door Notes stirred up a hot discussion in the U.S. To many Americans, It was the United States that, through the Open Door notes, rescued China from being carved up by the European Powers, and the Open Door Notes was thus endowed with a special meaning. In the opinion of many Americans, the initiation of the Open Door note demonstrated the increase of American international influence. Several months before the Spanish-American War, U.S. government refused a suggestion by Britain government for “Anglo-American cooperation in opposing action by foreign Powers which may tend to restrict freedom of commerce of all nations in China.”30In Jan., 1900, when Secretary John Hay announced to the public that U.S had sent an Open Door note to foreign Powers by itself and had received warm responses, the public hailed it as a great achievement, even “greater than the Spanish-American War.”31 The Open Door note, The Independent declared, marked out “a new policy for this 29 Wa Dexi: Wa Dexi Quanluan Bij i( Alfred Von Waldersee: Notes on the Boxer Rebellion), translated from German into Chinese by Wang Guangqi, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, 2008, p. 87. 30 Cited by Marilyn Blatt Young, The Rhetoric of Empire: American China Policy, 1895-1901, Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press, 1968, p.93. 31 Literary Digest, Jan. 13, 1900, p. 36. country” and it showed that “the time has gone by when America could be ignored in the councils of the nations,” and the United States “has forced the recognition of itself as a mighty influence in international politics and vindicated its right to a place second to none among the world Powers.” 32 James Wilson, the Secretary of Agriculture, claimed in the same way, “The work of Secretary Hay…supplements and complements the work of our army and navy. A year ago no nation would have listened to a proposition of this kind, but the whole world listens to the United States now.” 33 John Barrett, the United States Minister to Siam, even boldly asserted that “America is today the arbiter of China’s future.”34 Seeing China being in a danger of dismemberment again, American press demanded, “It is time for the U.S. …to preserve the integrity of China…and Open Door.” 35 During the Boxer Movement, not a few Americans showed their support to the allied military action of their government with other Powers on the ground that force could “teach” the Chinese a lesson, save their nationals besieged by the Boxers, and also win the respect of other Powers for the Open Door principle.36After the second Open Door note was issued, more and more Americans were convinced that the United States had dominated the situation of China. As The New York Weekly Tribune said, the July 3rd circular “place the United States…distinctly in the lead as a policy maker of the Powers in their relations with China,” and the United States will “continue in the lead in solving the world haunting Chinese problem.” 37 Although the military power of the United States was not stronger than that of all the other Powers, the two Open Door notes convinced Americans that their country not only had joined the club of world Powers but also had “exerted great influence on the operations now being conducted in China” 32 38 “The Open Door in China,” The Independent, Jan. 11, 1900. “The Open Door Agreement,” New York Times, Jan. 6, 1900. 34 “America in Far East,” New York Times, Jun.2, 1899. 35 “The Duty of America in China,” The Independent, Jun. 14, 1900. 36 Even the anti-imperialist Springfield Republican said, “The only assurance of an ‘open door’ still rests upon our ability to keep it open by force.” See Springfield Republican, in the Literary Digest, Jun. 13, 1900. 37 “Editorial”, The New York Weekly Tribune, July 12, 1900. 38 “The Concert and Its Leader,” New York Tribune, Aug. 4, 1900. 33 The Open Door Notes also distinguished the United States from European Powers. In their interpretations of the origin of the Boxer Movement, some Americans pointed out that, besides the barbarity of the Chinese, European Powers’ land-grabbing policy was also one of the reasons for the uprising. William W. Rockhill, the writer of the Open Door note, discussed in Forum, “The acquisition by European Powers of these various strips of territory along the coast of China has done more perhaps than anything else to intensify the anti-foreign and anti-missionary feeling of a conceited and ignorant people, who, from the fact that the seizures of Kiao-chao and of Kuang-chao Wan were made ostensibly as punishments for the murder, by bandits, of foreign missionaries, have conceived the idea that the missionaries are the prime cause of all their present troubles and humiliations.”39 While defining the European policy of China as being “grasping” and “selfish”, Americans emphasized the innocence and benevolence of their Open Door policy. In an interview, W. J. Bryan who was the Democratic candidate for the presidential election of 1900 expressed his opinion on the situation in China:40 For several years European nations have been threatening to dismember China and it is not strange that their ambitions designs should arouse a feeling of hostility toward foreigners. That feeling, however, ought not to be directed against American citizens, and will not if our nation makes it known that it has no desire to grab land or to trespass upon the rights of China….I will be better for our merchants to have it known that they seek trade only when trade is mutually advantageous. It will be better for our missionaries to have it known that they are preaching the gospel of love and are not the forerunners of fleets and armies. As an anti-imperialist who criticized the Republican administration for its colonization of the Philippines, Bryan disliked European nations’ land-grabbing policy toward China. However, as his words demonstrated, American policy of China was different from European nations’, as the United States did not want Chinese 39 40 William Woodville Rockhill, “The United States and the Future of China,” Forum, May 1900. “W. J. Bryan on Chinese Question,” New York Times, Jul. 21, 1900. territory and it only pursued the Open Door policy which was to ensure the equal rights of trading and preaching throughout China. From American’s point of view, trade benefits both sides, as Bryan said, “trade is mutually advantageous;” and preaching was regarded as altruistic, because spreading the gospel could uplift China. A Presbyterian missionary in China and president of Union College at Tungchou once wrote, “Christian civilization will bring to China a truer conception of the nature of man, a better understanding of his relations and duties, of his dignity and destiny.”41If European policy was selfish and destructive which aroused the anti-foreign feeling of the Chinese, the American policy toward China manifested by the Open Door notes was regard as “frank, just and generous”, as Outlook said, “it has taken into account the interests of China quite as much as the interests of our own citizens.”42 Furthermore, in Americans’ mind, it was the United States that rescued China from the storm of partitioning by the European Powers. Although the first Open Door note admitted the “sphere of influence” of other Powers on Chinese territory, when explaining to the public, Rockhill attributed the integrity of Chinese territory to American policy, the United States “temporarily at least, … put a stop to the grab policy… and had also shown the Peking Government that the integrity of the country is not menaced, that the aim of the Powers henceforth is the peaceful development of the natural resources and vast trade of China…”. Rockhill continued, “By its action, therefore, the Government of the United States has not only served the cause of peace and civilization, but has rendered a vast service to China.”43 The second Open Door note, which clearly stated “to preserve Chinese territorial and administrative entity”, convinced Americans that they saved China. A writer in Harper’s Weekly asked readers, “Does any one doubt now that if our course, backed as it was by Great Britain, had been otherwise, China would not be in process of dismemberment?” Even John Hay, in conversation with an adviser some years later, insisted upon the anticolonial dimension of the Open Door note: “We have done the Chinks a great service,” he 41 42 43 D. Z. Sheffiedl, “Chinese civilization: the Ideal and the Actual,” Forum, July, 1900. “The Administration and China,” Outlook, Sep. 8, 1900. William Woodville Rockhill, “The United States and the Future of China,” Forum, May 1900. declared, “which they don’t seem inclined to recognize.” 44 The following cartoon (Cartoon 2) illustrated this point very well. In this cartoon, Uncle Sam was standing in front of the gate of “China,” protecting China with “American Diplomacy” from the occupation of other Powers. (Cartoon 2: “Protecting China”,Life, 1900,Cited by Michael H. Hunt, Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987, p. 74.) As discussed above, Americans created a myth of protection of China in the discussions of the Open Door notes. In this myth, the complexity of the history of the Open Door policy was neglected, and the Open Door was represented not as a matter of self-interest but as a moral and altruistic conduct. It seems that Americans sought 44 Matthew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: the United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917, New York: Hill and Wang, 2000, p. 33. not domination but deliverance. Although the American navy was cooperating with that of other Powers to suppress the Boxer Movement when the July 3rd circular was sent, the United States differentiated itself from the European nations: European nations were aggressors and imperialists, whereas the United States was an anti-imperialist who rescued China from the dismemberment. When Americans regard themselves as the protector or benefactor of the Chinese, the paternalism began to dominate their attitudes toward China The Formation of the American Paternalism toward China Before 20th century, the Americans hold the same opinion with the Europeans that Chinese was a barbaric and backward race. However, due to the insufficient power, the influence of the United States was limited to the Western Hemisphere for a long time before the late 19th century. Therefore, Americans’ attention was rarely placed on the situations of China except the missionaries’. With the success in the Spanish-American war, Americans realized the increase of their international influence. In 1900 when the Boxer Movement occurred, the United States sent armies with European nations to suppress the uprising, which was considered to assume the responsibility of a civilized Power: “to defeat barbarians” and “to restore order”. 45 When the Open Door notes were issued, Americans became not only more confident of their power but also more assured of their role in China: unlike the greed European nations who planned to partition China, the benevolent U.S. saved China from dismemberment. The superiority of the civilized over barbarians and the self-image of “being benevolent” helped Americans to develop a paternalistic attitude toward China. When Americans looked at the Chinese with paternalistic sentiment, they saw the Chinese as a little boy. The atrocities of the Chinese in the Boxer Movement were thought to reflect their immaturity and irrationality. This is similar to the situation that a little boy behaved inappropriately. Despite of continuing criticism of Chinese 45 “the Duty of the Powers in China,” New York Tribune, Jun. 20, 1900. anti-foreign activities, a great number of articles in American press expressed their sympathies with China, who had to pay huge indemnity demanded by European nations. The Cartoon 3 illustrated this point. In Cartoon 4, China was painted as a crying boy whose pigtail was stepped on by Powers. Apparently, contrary to the image of the “barbaric” Chinese popularized in the late 19th century, the Chinese in Cartoon 4 was weak and helpless, with his knife falling down from his hands. (Cartoon 3, “Demand for Indemnity”, Los Angeles Times, Jul. 22, 1900.) (Cartoon 4: “At the end of his rope”, Literary Review, July 14, 1900.) For such weak and helpless China, Americans thought that they might be the only country to save China and to serve as parents to forgive and educate it. The following cartoon (Cartoon 5) was printed in Sep. 1900. In the cartoon, A Chinese standing on one of his knees was begging the Uncle Sam for a mercy (the position of the Chinese was weird, because the body language of the Chinese then was that they always stood on both of their knees not on one knee.) The Uncle Sam stood besides the Chinese, with his arm folded across his chest and a pistol holding in his hand. The whole picture evidently demonstrated the superiority of the Uncle Sam over the Chinese. The title of this cartoon was “justice or mercy.” Given the atrocious activities of the Chinese, Americans thought it just and reasonable to punish the Chinese. The image of the Uncle Sam holding a pistol in his hand suggested that the United States had the right and the power to punish China. But interestingly, the other choice was “mercy”, which meant, if the United States did not punish China, it was because the United States showed mercy to China, not because the Chinese should not be punished. The “mercy” articulated Americans’ imagination of their relationship with China: The Chinese who made mistakes needed the care and the benefaction by Americans, while Americans, despite of criticizing the barbarity and atrocity of the Chinese, tended to be merciful to China: parents (Americans) would finally forgive their children (Chinese). (Cartoon 5: “Justice or Mercy”, Leslie’s Weelky, Sept. 1900.) Conclusion In American history, paternalism once predominate the attitude of the white towards the nonwhite races, like African Americans and Native Americans. However, the Boxer Movement and the Open Door notes made paternalism became the dominate discourse in the American image of China. In the opinions of many Americans, China was backward in the hierarchy of civilization, and moreover, the Boxer Movement had shown the threat of a Barbaric China toward the world. Since the United States had saved China from being carved up by European nations and had assumed the responsibility of protection, it was obviously America’s duty to educate China. Therefore, Paternalism was not only dominating the American image of China, it also began to shape American polices and actions toward China. In the early 20th century, many Americans thought they had the duty to educate the Chinese and to help China develop in a right way, so they carried out a series of programs. No matter the remission of the Boxer Indemnity, the effort to reform American currency, or various programs sponsored by missionaries, foundations and universities, these were all considered to civilize, uplift and educate China. After the Boxer Movement was suppressed, Chinese government was forced to sign a treaty with western countries, agreeing to pay a large number of the Boxer Indemnity to eleven countries. American missionary Gilbert Reid expressed his opinion on this treaty, “The punishment inflicted on China dos not mean that China has no opportunity or stimulus for reform and advancement; the punishment is rather a chastisement intended for China’s good,” he declared, as “this necessitates financial reform, and may mean the salvation of China.”46The statement of Reid clearly demonstrated a condescending paternalistic attitude held by Americans: they knew what was good for the Chinese, and what they did was “intended for China’s good”. Paternalism thus justified the control of China by the United States in the name of parental care or in other words, “for China’s good”. 46 Gilbert Reid, “The Peace Proposals to China,” New York Evangelist, Apr. 4 1901.