Clinical features of Todd's post

advertisement

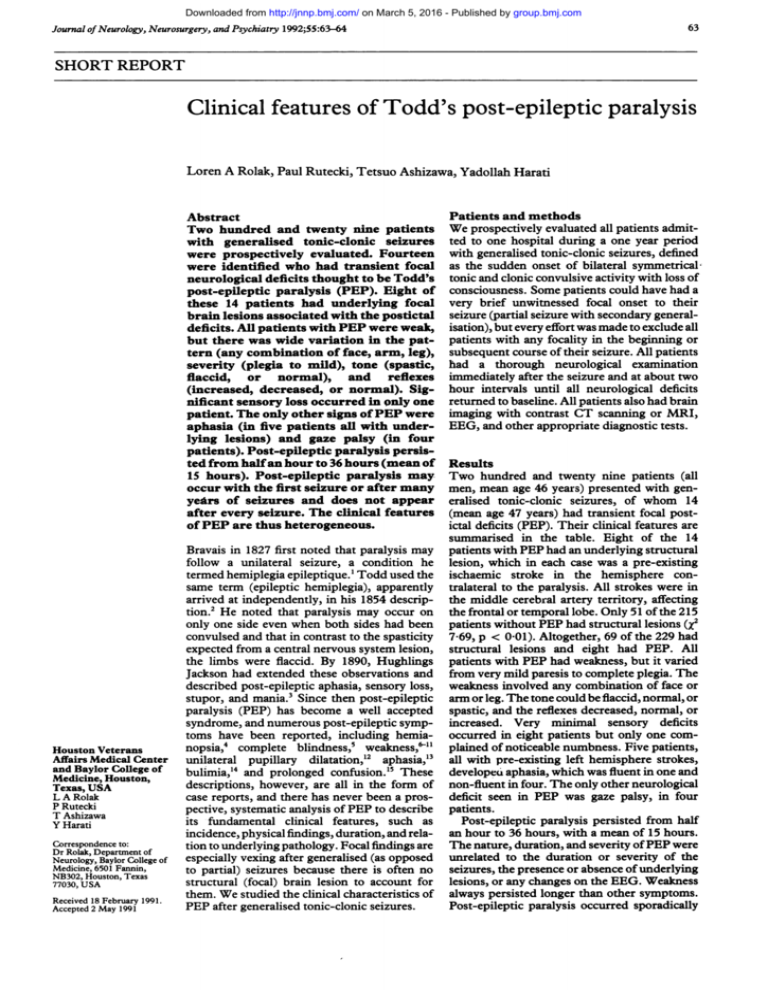

Downloaded from http://jnnp.bmj.com/ on March 5, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com 63 Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1992;55:63-64 SHORT REPORT Clinical features of Todd's post-epileptic paralysis Loren A Rolak, Paul Rutecki, Tetsuo Ashizawa, Yadollah Harati Abstract Two hundred and twenty nine patients with generalised tonic-clonic seizures were prospectively evaluated. Fourteen were identified who had transient focal neurological deficits thought to be Todd's post-epileptic paralysis (PEP). Eight of these 14 patients had underlying focal brain lesions associated with the postictal deficits. All patients with PEP were weak, but there was wide variation in the pattern (any combination of face, arm, leg), severity (plegia to mild), tone (spastic, flaccid, or normal), and reflexes (increased, decreased, or normal). Significant sensory loss occurred in only one patient. The only other signs of PEP were aphasia (in five patients all with underlying lesions) and gaze palsy (in four patients). Post-epileptic paralysis persisted from half an hour to 36 hours (mean of 15 hours). Post-epileptic paralysis may occur with the first seizure or after many years of seizures and does not appear after every seizure. The clinical features of PEP are thus heterogeneous. Houston Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA L A Rolak P Rutecki T Ashizawa Y Harati Correspondence to: Dr Rolak, Department of Neurology, Baylor College of Medicine, 6501 Fannin, NB302, Houston, Texas 77030, USA Received 18 February 1991. Accepted 2 May 1991 Patients and methods We prospectively evaluated all patients admitted to one hospital during a one year period with generalised tonic-clonic seizures, defined as the sudden onset of bilateral symmetrical; tonic and clonic convulsive activity with loss of consciousness. Some patients could have had a very brief unwitnessed focal onset to their seizure (partial seizure with secondary generalisation), but every effort was made to exclude all patients with any focality in the beginning or subsequent course of their seizure. All patients had a thorough neurological exam-ination immediately after the seizure and at about two hour intervals until all neurological deficits returned to baseline. All patients also had brain imaging with contrast CT scanning or MRI, EEG, and other appropriate diagnostic tests. Results Two hundred and twenty nine patients (all men, mean age 46 years) presented with generalised tonic-clonic seizures, of whom 14 (mean age 47 years) had transient focal postictal deficits (PEP). Their clinical features are summarised in the table. Eight of the 14 Bravais in 1827 first noted that paralysis may patients with PEP had an underlying structural follow a unilateral seizure, a condition he lesion, which in each case was a pre-existing termed hemiplegia epileptique.' Todd used the ischaemic stroke in the hemisphere consame term (epileptic hemiplegia), apparently tralateral to the paralysis. All strokes were in arrived at independently, in his 1854 descrip- the middle cerebral artery territory, affecting tion.2 He noted that paralysis may occur on the frontal or temporal lobe. Only 51 of the 215 only one side even when both sides had been patients without PEP had structural lesions (X2 convulsed and that in contrast to the spasticity 769, p < 0-01). Altogether, 69 of the 229 had expected from a central nervous system lesion, structural lesions and eight had PEP. All the limbs were flaccid. By 1890, Hughlings patients with PEP had weakness, but it varied Jackson had extended these observations and from very mild paresis to complete plegia. The described post-epileptic aphasia, sensory loss, weakness involved any combination of face or stupor, and mania.3 Since then post-epileptic arm or leg. The tone could be flaccid, normal, or paralysis (PEP) has become a well accepted spastic, and the reflexes decreased, normal, or syndrome, and numerous post-epileptic symp- increased. Very miniimal sensory deficits toms have been reported, including hemia- occurred in eight patients but only one comnopsia,4 complete blindness,5 weakness,&-I plained of noticeable numbness. Five patients, unilateral pupillary dilatation,"2 aphasia,'3 all with pre-existing left hemisphere strokes, bulimia,'4 and prolonged confusion.'5 These developeui aphasia, which was fluent in one and descriptions, however, are all in the form of non-fluent in four. The only other neurological deficit seen in PEP was gaze palsy, in four case reports, and there has never been a prospective, systematic analysis of PEP to describe patients. Post-epileptic paralysis persisted from half its fundamental clinical features, such as incidence, physical findings, duration, and rela- an hour to 36 hours, with a mean of 15 hours. tion to underlying pathology. Focal findings are The nature, duration, and severity of PEP were especially vexing after generalised (as opposed unrelated to the duration or severity of the to partial) seizures because there is often no seizures, the presence or absence of underlying structural (focal) brain lesion to account for lesions, or any changes on the EEG. Weakness them. We studied the clinical characteristics of always persisted longer than other symptoms. Post-epileptic paralysis occurred sporadically PEP after generalised tonic-clonic seizures. Downloaded from http://jnnp.bmj.com/ on March 5, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com 64 Rolak, Rutecki, Ashizawa, Harati Table Clinicalfeatures ofpatients with post-epileptic paralysis (PEP) Age (years) Duration of epilepsy (years) Cause of seizures 50 10 2 3 4 5 6 7 28 25 31 36 28 51 1st seizure 15 1 3 5 1st seizure Alcohol withdrawal Idiopathic Idiopathic Idiopathic Idiopathic Idiopathic Stroke 8 54 1st seizure Stroke 9 48 1 Stroke 10 11 61 63 10 8 Stroke Stroke 12 70 6 Stroke 13 47 8 Stroke 14 66 24 Stroke Patient 1 Weakness EEG Severity NL 0/5 4+/5 NL NL NL NL NL Focal theta Focal spikes + delta Focal spikes + delta NL Focal theta Focal spikes + delta Focal spikes + theta NL Pattern Tone Duration of PEP (hours) Reflexes Extensor plantar Yes Gaze palsy 8 NL No No No No No No None Numbness None None None Gaze palsy 36 4 24 24 18 6 No Gaze palsy + aphasia 12 Other signs F, A, L l 4/5 4/5 4+/5 3/5 4/5 A A, L F, A, L A, L A, L A, L NL NL NL NL 0/5 A, L l 4 + /5 A NL NL No Aphasia 24 4/5 4/5 F, A L NL T t NL No No Aphasia Aphasia 36 8 0/5 F, A, L 1 No Gaze palsy 6 4/5 A, L NL NL No None 05 4/5 A, L t T Yes Aphasia 8 It T T I t NL F = face, A = arm, L = leg, t = increased, I = decreased, NL = normal. and did not follow every seizure. Some patients had suffered recurrent seizures for years before their first episode of PEP, and most had subsequent seizures without associated PEP. There was no apparent reason why some seizures resulted in PEP and others did not. Six patients with PEP had a baseline abnormal EEG (see table), which in each case showed a slow wave (theta or delta) focus in the contralateral frontal or temporal lobe, corresponding to an underlying ischaemic stroke. Four of the tracings also had epileptiform spike activity accompanying the focal slowing. Only one patient (number 2, with idiopathic seizures) had an EEG recorded during his PEP, and it showed no abnormality. Discussion Transient focal neurological deficits after an epileptic seizure are often called Todd's paralysis in recognition of their description by the British neurologist Robert Todd.2 Since then, research has focused primarily on possible mechanisms of post-epileptic paralysis,"6 but its clinical features have never been systematically studied, and there is almost no information about the nature, duration, or aetiology of the deficits that occur after a seizure. Our conclusions about PEP are limited by the population studied (adult male veterans) and the restriction to generalised tonic-clonic seizures without ictal focality. In this group, PEP was a heterogeneous syndrome encompassing a variety of neurological signs including aphasia, gaze palsy, weakness, and (rarely) numbness. The motor deficits were highly variable, from mild to severe, flaccid to spastic, focal to hemiparetic. Abnormalities never persisted beyond 36 hours. Most patients with PEP had an underlying structural lesion but, interestingly, in many (43%) no cause was found. The aetiology of PEP is not clear. It may be due to neuronal exhaustion from hypoxia or substrate depletion because a localised region of the brain is already damaged or is more severely affected by the seizure, or because some underlying condition, such as vascular disease, predisposes to insufficient metabolism.6 Alternatively, it may result from inhibitory neuronal discharges,7 arterial venous shunting,8 9 or release of endogenous inhibitory (possibly opioid) substances."6 Our study, though not intended to address the aetiology of PEP, demonstrates its great clinical diversity and thus suggests that it may have multiple causes. 1 Bravais LF. Recherches sur les symptomes et le traitement de l'epilepsie hemiplegique. Paris: Faculte de Medecine de Paris, 1827. 2 Todd RB. Clinical lectures on paralysis, certain diseases of the brain, and other affections of the nervous system. London: John Churchill, 1854;284-307. 3 Jackson JH. The Lumleian lectures on convulsive seizures. Br Med J 1890;1:821-7. 4 Salmon JH. Transient postictal hemianopsia. Arch Ophthalmol 1968;79:523-5. 5 Kosnik E, Paulson GW, Laguna JF. Postictal blindness. Neurology 1976;26:248-50. 6 Meyer JS, Portnoy HD. Post-epileptic paralysis. A clinical and experimental study. Brain 1959;82:162-85. 7 Efron R. Post-epileptic paralysis: Theoretical critique and report of a case. Brain 1961;84:381-94. 8 Yarnell PR, Burdick D, Sanders B, Stears J. Focal seizures, early veins, and increased flow. Neurology 1974;24:512-6. 9 Yarnell PR. Todd's paralysis: a cerebrovascular phenomenon? Stroke 1975;6:301-3. 10 Collier HW, Engelking K. Todd's paralysis following an interscalene block. Anesthesiol 1984;61:342-3. 11 Youkey JR, Clagett GP, Jaffin JH, et al. Focal motor seizures complicating carotid endarterectomy. Arch Surg 1984; 119:1080-4. 12 Gadoth N, Margalith D, Bechar M. Unilateral pupillary dilitation during focal seizures. JNeurol 1981;225:227-30. 13 Koemer M, Laxer KD. Ictal speech, postictal language dysfunction, and seizure lateralization. Neurology 1988; 38:634-6. 14 Remick RA, Jones MW, Campos PE. Postictal bulimia. J Clin Psychiatry 1980;41:256. 15 Biton V, Gates JR, Sussman LD. Prolonged postictal encephalopathy. Neurology 1990;40:963-6. 16 Tortella FC, Long JB. Endogenous anticonvulsant substance in rat cerebrospinal fluid after a generalized seizure. Science 1985;228:1 106-8. Downloaded from http://jnnp.bmj.com/ on March 5, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com Clinical features of Todd's post-epileptic paralysis. L A Rolak, P Rutecki, T Ashizawa and Y Harati J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992 55: 63-64 doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.1.63 Updated information and services can be found at: http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/55/1/63 These include: Email alerting service Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the box at the top right corner of the online article. Notes To request permissions go to: http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions To order reprints go to: http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform To subscribe to BMJ go to: http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/