C O M M E R C I A L L I T I G AT I O N

Establishing a

Rightful Claim of

Patent Infringement

U.C.C. 2-312(3)

By Daniel J. Herling

and Leyla Mujkic Pasic

A review of the body

Every attorney who has tried a breach of contract case

knows well that the interpretation assigned to a contractual term at issue makes or breaks his or her case. A sale of

a good under the Uniform Commercial Code (U.C.C.)—

of case law in this area,

as well as the facts

that defendants have

had to establish to

fight off an allegation

of “rightfulness.”

often ultimately achieved only after a series of quotes, purchase orders, acknowledgments, invoices, and an exchange of

the parties’ “boilerplate” terms and conditions—may be threatened if contracting

parties have not specifically negotiated a

crucial contractual term and agreed upon

it in writing. Yet commonly even the most

sophisticated contracting parties fail to

foresee all potential threats to their sales

transaction, which exposes their contract

to uncertainty and costly litigation. Such

is the case if contracting parties fail to anticipate the lurking threat of a third-party

patent infringement suit. In a failure to

anticipate, contracting parties may forgo

negotiating and capturing in writing a

mutually acceptable indemnification provision. In the event that such a threat materializes into an actual third-party claim of

patent infringement, a contract’s indemnification provision may well become the most

important contractual term, materially altering the parties’ respective rights. If the

parties have not expressly agreed to a contract’s indemnification provision, for example, if an indemnification provision either

is entirely missing from the contract or is

only addressed in each party’s boilerplate

forms, a buyer and seller may have to litigate for years to determine their respective

rights. If a seller’s boilerplate indemnification provision differs from that of the buyer,

a court will deem neither indemnification

provision part of the contract, based on lack

of mutual assent. Instead, the two different

terms will drop out under U.C.C. §2-207(3),

and a court will deem the contract to “consist of those terms on which the writings

of the parties agree, together with any supplementary terms incorporated under any

other provisions of” the U.C.C.

In the event of a third-party claim of

patent infringement, the U.C.C. does offer

a supplementary term under §2-312, commonly known as the “implied warranty

against infringement,” which permits

indemnification in the event that a poten-

Daniel J. Herling is a partner and Leyla Mujkic Pasic is an associate in the San Francisco office of Keller

and Heckman LLP. Mr. Herling is head of the firm’s Litigation Practice Group and focuses his trial practice on

complex commercial litigation. He is a former chair of the DRI Professional Liability Committee and a member

of the FDCC. Ms. Pasic focuses her trial practice on commercial litigation and product liability. In addition to

her involvement with DRI, Ms. Pasic is active in the San Francisco Bar Association and related organizations.

■ 60 For The Defense February 2011

n

n

© 2011 DRI. All rights reserved.

tial indemnitee successfully establishes

the elements of the provision. Specifically,

U.C.C. §2-312(3) states:

Unless otherwise agreed a seller who is

a merchant regularly dealing in goods of

the kind warrants that the goods shall be

delivered free of the rightful claim of any

third person by way of infringement or

the like but a buyer who furnishes specifications to the seller must hold the

seller harmless against any such claim

which arises out of compliance with the

specifications.

Thus, to prove that a potential indemnitor breached the statutory warranty, an

indemnitee must show that (1) the seller

was a merchant regularly dealing in goods

of that kind, (2) the goods were subject to a

“rightful claim” of infringement of a third

party upon delivery, (3) the buyer did not

furnish specifications to the seller, and

(4) the parties did not form another agreement. See, e.g., 84 Lumber Co. v. MRK Technologies, Ltd., 145 F. Supp. 2d 675, 678–79

(W.D. Pa. 2001). Though three of the four

elements are self-­evident—either the seller

is or is not a merchant, the buyer did or

did not furnish specifications, and the

parties did or did not form another agreement—one element is not: what constitutes

a “rightful claim”? And the volume of case

law adjudicating the “rightful” nature of an

underlying third-party claim of infringement is relatively scant. The cases that

have addressed “rightfulness,” furthermore, have defined it along a continuum.

Whether a third-party claim of infringement is “rightful” is a fact question for

a jury to decide. See, e.g., SunCoast Merchandise Corp. v. Myron Corp., 393 N.J.

Super. 55 (N.J. App. Div. 2007), cert. denied,

194 N.J. 270, 944 A.2d 30 (N.J. 2008). If

an underlying infringement claim was

adjudicated and a jury issued a verdict of

infringement against the indemnitee, the

jury considering the indemnity case may

be convinced that the underlying claim of

patent infringement was “rightful.” However, an indemnitee will surely stumble in

his or her efforts to prove rightfulness of an

underlying claim if a jury issued no such

verdict, for example, if the parties settled

the underlying patent infringement suit.

Such a situation also imposes great burdens

on a potential indemnitor warding off allegations of rightfulness.

To date, at least one case looking at

whether the underlying claim of infringement was rightful has been tried by a jury.

See Linear Technology Corporation v. Applied Materials Inc. et al., Santa Clara County

Superior Court Case No. 102CV806004. In

that case, after nine years of litigation and

a six-week trial, the jury held in favor of defendants, the indemnitors, finding that the

plaintiff, the indemnitee, failed to establish

by a preponderance of the evidence that the

defendants breached the statutory warranty

against infringement.

This article will first look at the body of

case law addressing the requirement that

a claim of infringement be “rightful” for

a statutory indemnity provision to apply,

and it will then turn to the facts that the

defendants in Linear v. Applied Materials

et al. had to establish to fight off the allegation of rightfulness made by the plaintiff,

the indemnitee.

The Evolution of the “Rightful

Claim” Analysis

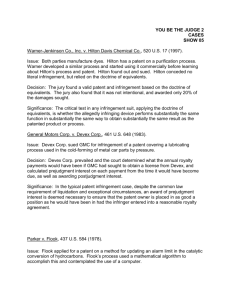

The earliest case examining what constituted a “rightful claim” of infringement

was Cover v. Hydramatic Packing Co., Inc.,

although the Cover court did not actually

define it. 83 F.3d 1390 (Fed. Cir. 1996). In

that case, the specific question involved

preemption—whether 35 U.S.C. §287(a) of

the patent code preempted §2312(c) of the

Pennsylvania Commercial Code. The Federal Circuit held that the two did not conflict “in that Pennsylvania’s commercial law

neither renders compliance with the patent

code a ‘physical impossibility’ nor ‘stands

as an obstacle to the accomplishment and

execution’ of the patent laws.” Id. at 1394.

In dicta, the Federal Circuit suggested that

a rightful claim did not require a finding

of absolute patent liability: “…to adopt Sea

Gull’s [the appellee’s] ‘rightful claim’ argument would not lead to judicious public

policy inasmuch as parties would eschew

settlement and be forced to go to trial to

discern whether a ‘rightful claim’ exists under federal patent law. We cannot lend our

imprimatur to such a policy.” Id. at 1394.

A subsequent case more directly implicated the rightful claim analysis when the

court addressed whether it had to “decide

a substantial question of federal patent law

in order to determine whether the goods”

at issue were “delivered free of a right-

ful claim of infringement.” 84 Lumber

Company v. MRK Technologies, LTD, 145

F. Supp. 2d 675 (W.D. Pa. 2001). In 84 Lumber, the defendants manufactured handheld laser devices used to scan bar codes

on merchandise. Id. at 676. The plaintiff

purchased the equipment from the defendants and was subsequently sued for patent

infringement by a third party, Lemelson

If contracting parties

fail to anticipate the

lurking threat of a… thirdparty claim of patent

infringement, a contract’s

indemnification provision

may well become the most

important contractual term.

Medical, Education & Research Foundation, LP. Id. at 677. The plaintiff settled the

underlying patent infringement lawsuit for

$ 40,000 and then filed a claim against the

defendants, alleging only a breach of the

implied warranty against infringement

under the Pennsylvania statute adopting

without change U.C.C. §2-312(3). Id. The

defendants sought to remove the case to

federal court, asserting federal jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1331, 1338, and 1441.

Id. at 677. They contended that a “rightful

claim” of infringement was “a just or legally

established claim,” or “[a] legally enforceable claim.” Id. Under the defendants’ theory, “a court cannot determine whether or

not they must indemnify 84 Lumber for

the value of its settlement of the Lemelson Suit, without first finding that Lemelson had a rightful, legally enforceable claim

of infringement.” Id. Removal was proper,

according to the defendants, because patent law was a necessary element of the

plaintiff’s breach of contract action. Id.

The plaintiff, on the other hand, contended that the case should have been remanded to state court because “a ‘rightful

For The Defense February 2011 61

n

n

C O M M E R C I A L L I T I G AT I O N

claim’ does not require a determination of

actual liability, and thus, disposition of the

complaint does not require the resolution of

a substantial question of federal patent law.

Any patent issues that may need to be addressed are merely tangential, and may be

competently adjudicated by the Pennsylvania state courts.” Id. Without adopting either definition, the district court stated that

Existing case law requires

that an evaluative inquiry

into the merits of the

underlying infringement claim

be made before deciding

whether the underlying

claim of infringement

against the buyer-­

indemnitee was “rightful.”

“if claims of patent infringement are seen as

marks on a continuum, whatever a ‘rightful claim’ is would fall somewhere between

purely frivolous claims, at one end, and

claims where liability has been proven, at

the other.” Id. at 680. The court then stated

that it did not need to decide what precisely

constituted a rightful claim of patent infringement to decide that it had jurisdiction over the plaintiff’s claims.

The meaning of the phrase “rightful

claim” was next addressed by the California Court of Appeals in the trademark context following an order granting summary

judgment in favor of the defendant. Pacific

Sunwear of California, Inc. v. Olaes Enterprises, Inc., 167 Cal. App. 4th 466 (Cal. Ct.

App. 2009). The lawsuit alleged that the defendant, Olaes Enterprises, breached the

statutory warranty codified in §2312(3) of

the California Uniform Commercial Code.

Id. at 470. Pacific Sunwear sought monetary damages for the alleged breach to compensate it for litigation expenses incurred

defending against a third-party trade-

62 For The Defense February 2011

n

n

mark infringement lawsuit that arose from

Pacific Sunwear’s sale of T-shirts purchased

from Olaes. Id. The trial court granted the

defendant’s motion for summary judgment

on the ground that the third-party claim

did not constitute a “rightful claim” of

infringement under §2312(3), and thus the

defendant did not breach the statutory warranty. Id. The issue on appeal was whether

the trial court properly ruled on a motion

for summary judgment that the §2312(3)

warranty did not apply because the trademark suit filed by the third party was not a

rightful claim of infringement. Id. at 473.

On appeal, the parties offered very different definitions of the phrase “rightful

claim.” Id. The defendant argued that “a

rightful claim is a valid claim, i.e., one that

has proven, or will likely prove, meritorious

in litigation.” Id. The plaintiff argued that

“any claim ‘in the form of litigation’ constitutes a rightful claim regardless of its underlying merits.” Id. Citing 84 Lumber, the

California Court of Appeals stated that “the

correct interpretation of section 2312(3) lies

somewhere in between these positions.” Id.

The California Court of Appeals examined both the official commentary to U.C.C.

§2-312(3), adopted in California without

change, as well as the public policy rationales underlying California Uniform Commercial Code §2312, before holding that

the implied warranty against infringement covers a broad scope of infringement

claims and is not limited to claims that

ultimately will prove successful in litigation. Id. at 481. Specifically, the Pacific Sunwear court held that “the warranty against

rightful claims applies to all claims of

infringement that have any significant and

adverse effect on the buyer’s ability to make

use of the purchased goods, excepting only

frivolous claims that are completely devoid

of merit.” Id. The Pacific Sunwear court

went on to write,

the existence of litigation is neither necessary nor, in itself, sufficient to establish that a claim is ‘rightful.’ A claim

of infringement may be rightful under

section 2312(3) whether or not it is ultimately pursued in litigation. For example, a claim may be deemed rightful if

the buyer, prior to any litigation, voluntarily ceases to use purchased goods due

to a third party claim of infringement.

And, contrary to PacSun’s [Pacific Sun-

wear’s] suggestion, the mere filing of litigation will not necessarily establish

that a claim is ‘rightful.’ As the courts

are well aware, a third party may file a

complaint and pursue litigation despite

the absence of any merit to the underlying contention.

Id. at 482.

The Pacific Sunwear court also noted

that if it accepted Pacific Sunwear’s argument that the “warranty is triggered by the

filing of litigation, without any evaluative

inquiry into the merits of the underlying

claim itself, we would effectively be reading

the term ‘rightful’ out of the statute.” Id. at

482 n. 10. Even though it rejected Pacific

Sunwear’s contention that filing the underlying suit triggered the statutory warranty,

the appellate court concluded that the trial

court had erred in granting the defendant’s

motion for summary judgment. Specifically, the appellate court noted that the

existence of the underlying litigation created “a triable issue of material fact,” on the

claim’s rightfulness. Id. at 483.

Pacific Sunwear, thus, requires an evaluative inquiry into the merits of the underlying infringement claim in indemnification

cases. It requires determining whether the

underlying infringement claim was “frivolous,” meaning, completely devoid of merit,

and whether it had “any significant and

adverse effect, through the prospect of litigation or otherwise, on the buyer’s ability to make use of the purchased good.”

Id. Because Pacific Sunwear was a trademark infringement case, however, it did not

address whether comparing the patents at

issue with the accused products was necessary to establish the rightful nature of the

underlying claim.

Shortly after the Pacific Sunwear opinion, the Northern District of California

examined a different though related issue:

how far must a patent infringement case

proceed for an indemnitee to establish a

rightful claim of patent infringement under

the statutory warranty. Phoenix Solutions,

Inc. v. Sony Electronics, Inc., 637 F. Supp. 2d

683 (N.D. Cal. 2009). The specific question

in Phoenix Solutions was whether “claim

construction is required to assess a ‘rightful claim’ of patent infringement to sustain a breach of warranty claim.” Id. at 695.

In that case, the plaintiff, Phoenix

Solutions, sued Sony, alleging patent

infringement. Id. at 686. Sony then filed

a third-party complaint against Intervoice, Inc., alleging breach of the statutory warranty. Id. at 688. Phoenix Solutions

and Sony settled their patent infringement action. Id. at 689. Both Intervoice

and Sony moved for summary judgment

on Sony’s implied warranty claim, disagreeing on whether Phoenix Solutions’

infringement claims against Sony were

“rightful” under §2312(3) of the California

Commercial Code. Id. at 689. Sony argued

that “Phoenix’s infringement claims barred

Sony from manufacturing, importing or

using its IVR system and required Sony to

pay compensatory damages,” and thus, that

the allegations cast doubt on Sony’s rightful use of the IVR systems. Id. at 695. Sony

also pointed to the fact that it had to pay

for its defense against Phoenix Solutions.

Id. Intervoice argued that Sony’s noninfringement defenses to Phoenix Solutions’

claims demonstrated that Phoenix Solutions’ claims were not rightful and, in the

alternative, that claim construction was

required to assess a “rightful claim” of patent infringement to sustain a breach of

warranty claim. Id. at 695, 696.

The district court first rejected Intervoice’s argument that noninfringement

defenses generally demonstrate that a

claim is not rightful, stating instead that a

party’s defenses have no bearing on rightfulness since the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure liberally permit pleading in the

alternative. Id. In an effort to address Intervoice’s second contention, the district court

considered Pacific Sunwear, first noting

that because it “was a trademark infringement case, it did not address whether a

comparison of patents at issue with the

accused products was necessary.” Id. at

697. The district court then extended the

Pacific Sunwear reasoning to patent cases,

noting that merely filing litigation does not

establish that a claim is rightful, and evaluating the merits of the underlying claim

was necessary. Id. However, the court ruled

that claim construction was not required

for Sony’s breach of warranty claim to survive summary judgment: “the court finds

that Sony has met its burden of asserting

a rightful claim, for the present purposes

of surviving summary judgment, because

Phoenix’s infringement claims had a significant and adverse effect on Sony’s abil-

ity to make use of” the product at issue. Id.

The court noted that the case had advanced

beyond the “mere filing of an action,” and

the infringement-­related settlement terms,

submitted to the court under seal, indicated that “an evaluative inquiry was made

into the merits of the underlying claim

itself.” Id.

Thus, in a buyer-­indemnitee’s breach of

statutory warranty case against a seller-­

indemnitor, existing case law requires

that an evaluative inquiry into the merits

of the underlying infringement claim be

made before deciding whether the underlying claim of infringement against the

buyer-­indemnitee was “rightful.” As a natural consequence of that rule, not every

underlying claim of infringement will be

found to be rightful. Instead, only nonfrivolous claims having any significant and

adverse effect, through the prospect of litigation or otherwise, on the buyer’s ability to use the purchased goods will meet

the “rightfulness” requirement of the statutory warranty.

Applying the Above Principles,

at Least One Jury Has Held That

Plaintiff Failed to Establish the

“Rightfulness” of the Underlying

Claim of Infringement

At least one case demonstrates the complexity parties face proving or disproving

the applicability of a statutory warranty

and its attendant indemnity provision. In

Linear Technology v. Applied Materials, et

al., No. 102CV806004, the plaintiff, Linear

Technology, sued three manufacturers of

semiconductor equipment, Applied Materials, Novellus Systems, Inc., and Tokyo Electron Limited, in the Santa Clara County

Superior Court in 2001, alleging six causes

of action against them, including breach of

contract and breach of the statutory warranty. Linear’s claims, allegedly, stemmed

from its purchase of the defendants’ semiconductor equipment. Specifically, Linear contended that purchasing and using

the defendants’ semiconductor equipment

exposed it to an earlier patent infringement lawsuit initiated by a third party,

Texas Instruments. Linear contended that

the underlying patent infringement lawsuit, which was never tried before a jury,

resulted in a settlement agreement with

terms unfavorable to Linear.

Before the trial commenced, Linear settled its dispute with Applied Materials,

leaving Tokyo Electron and Novellus as the

remaining defendants in the Santa Clara

action. Before the jury began to deliberate, the court determined that Linear had

contracted separately with Tokyo Electron

and Novellus to purchase their equipment.

However, the court decided that the parties’

Only nonfrivolous claims

having any significant

and adverse effect… on

the buyer’s ability to use

the purchased goods will

meet the “rightfulness”

requirement of the

statutory warranty.

different indemnification provisions, contained only in their respective boilerplate

terms and conditions, did not become part

of the contract. Instead, the court instructed

the jury that the statutory warranty against

rightful claims of infringement became a

provision of Linear’s separate contract with

each, Tokyo Electron and Novellus.

During the course of the trial, Linear

sought to establish that it was entitled to

indemnification under the statutory warranty because it had been sued by Texas

Instruments for using the Tokyo Electron

and Novellus equipment. Consequently,

much of the trial focused on whether or

not Texas Instruments’ underlying patent

infringement claims against Linear were

“rightful.” Resolving the issue of “rightfulness” would ultimately decide whether the

defendants breached the statutory warranty against infringement and whether

Linear was entitled to indemnification.

In an effort to show that Texas Instruments’ patent infringement claims against

the defendants’ equipment were rightful,

Linear sought to prove by a preponderance

Patent, continued on page 78

For The Defense February 2011 63

n

n

Patent, from page 63

of the evidence that Texas Instruments’

infringement claims had a significant and

adverse affect on Linear’s ability to use the

machines, were not “frivolous,” and were

not a result of the defendants’ compliance with Linear’s specifications. Linear

argued that since the mere prospect of litigation establishes the first prong of the test,

the fact that it was actually sued by Texas

Instruments for patent infringement indicated that Linear’s ability to use the purchased equipment was significantly and

adversely affected.

Next, Linear attempted to establish

that Texas Instruments’ patent infringement claims were not “frivolous.” Relying on Pacific Sunwear, Linear argued

that it did not have to show that Texas

Instruments would have ultimately won

its patent infringement case, but that Texas

Instruments’ claims were not “totally and

completely without merit.” Among other

things, Linear attempted to prove the

“rightfulness” of the underlying patent

infringement claims by offering into evidence Texas Instruments’ claim charts,

the fact that Texas Instruments’ aggressively litigated its claims against Linear

for almost two years, and the fact that Linear settled the underlying patent infringement claims on unfavorable terms because

of the risk of an adverse result. Perhaps

most strongly, Linear relied on the jury

verdict in Texas Instruments’ separate lawsuit against nonparty Hyundai determining that the use of similar semiconductor

equipment by Hyundai had infringed the

same Texas Instruments patents. Linear

argued that the Hyundai verdict corroborated the rightful nature of Texas Instruments’ claims against Linear.

To defend against Linear’s allegations of

the “rightfulness” of the underlying patent

infringement claims, Tokyo Electron and

Novellus had to present substantial evi-

78 For The Defense February 2011

n

n

dence to support their contention that any

claim that the operation of their equipment by Linear infringed Texas Instruments’ patents was “frivolous,” therefore,

that the claim was not “rightful.” To do so,

the defendants examined the substance

of the underlying patents, which specified that the infringing tools had to operate “asynchronously.” The defendants’

offered detailed, factual and expert testimony explaining why the equipment

could not have operated in the manner

described in Texas Instruments’ patents.

Specifically, the defendants showed that

because their tools operated “synchronously,” Texas Instruments underlying

infringement claims were factually devoid

of merit, that is, “frivolous.” The defendants also presented evidence showing that

no court, including the Hyundai court, had

ever addressed whether Texas Instruments’

infringement claim against Linear actually had any merit. Finally, the defendants

showed that Linear never stopped using the

defendants’ equipment during the patent

litigation, nor that it replaced that equipment, so the underlying litigation had no

adverse effect on Linear’s ability to use

Tokyo Electron’s and Novellus’ equipment.

Because Texas Instruments’ infringement

claims were factually and legally devoid of

merit, and because they did not adversely

affect Linear’s ability to use the equipment,

the defendants argued, Texas Instruments’

claims were not rightful.

After the parties presented all the evidence, the judge instructed the jurors on

the elements of the statutory warranty

breach and provided them with a legal

definition of a “rightful claim.” Specifically, the court instructed the jurors that

to recover damages from either defendant

for breach of the statutory warranty, Linear

had to prove that (1) the goods supplied by

the defendants were not delivered free of a

rightful claim of infringement, and (2) Lin-

ear was harmed by that failure. The court

defined a “rightful claim” as “one that has

any significant and adverse effect on the

buyer’s ability to make use of the purchased

goods and is not frivolous.” It defined a

“frivolous claim” as “one that is factually

or legally devoid of merit.” The court also

specified that “the filing of a lawsuit alone

cannot establish that a claim of infringement is rightful,” but that a plaintiff, in this

case, Linear, did not need to show that “the

claim of infringement ultimately would

have been successful in order to establish

that the claim is rightful.”

Before deliberating, the jurors received

two identical special verdict forms, one for

Tokyo Electron and one for Novellus. The

first question on each form asked whether

the respective defendant had breached “the

statutory warranty incorporated into its

contract with Linear.” After considering all

of the evidence presented by the parties, the

jurors unanimously answered, “No.”

Conclusion

As the Linear case demonstrates, determining whether an underlying claim

of patent infringement is “rightful” is a

fact question that a jury must decide in

a dispute over indemnification involving U.C.C. §2-312. Though the law does

not require that underlying patent litigation ultimately result in a verdict against

the buyer-­indemnitee, it does require an

evaluative inquiry into the merits of the

underlying patent infringement claim. To

prevail on a statutory warranty claim, a

buyer-­i ndemnitee must demonstrate to

the jury that the underlying claim of patent infringement was not “frivolous” and

that it had a significant effect on the buyer’s ability to use the purchased goods.

Where the buyer-­indemnitee fails to present such evidence, he or she will also fail in

its breach of statutory warranty claim.