A Usability Survey at the University of Mississippi Libraries for the

advertisement

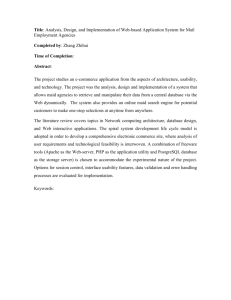

A Usability Survey at the University of Mississippi Libraries for the Improvement of the Library Home Page by Elizabeth Stephan, Daisy T. Cheng, and Lauren M. Young Available online 27 January 2006 A usability survey was conducted at the University of Mississippi Libraries as part of the ongoing assessment of the library and its services. By setting criteria to measure the success of the survey, librarians at UM were able to assess if the library home page successfully met the goals and mission statement of the library. INTRODUCTION Elizabeth Stephan is Business Reference Librarian/Assistant Professor, The University of Mississippi, MS 38677, USA bestephan@olemiss.eduN; Daisy T. Cheng is Head of Cataloging/Assistant Professor, The University of Mississippi, MS 38677, USA bdtcheng@olemiss.eduN; Lauren M. Young is Instructor/Outreach Services Librarian, Rowland Medical Library, The University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS 39216-4505, USA blmyoung@rowland.umsmed.eduN. The University of Mississippi Libraries has maintained a Web site since 1994. Its earliest version was based on a static format that provided access to the library catalog, a subject guide, a personnel directory, and library hours. The pages were poorly coordinated, the navigation not intuitive. A usability survey was administrated to a group of high school students in the summer of 2003 with the goal of collecting user feedback on the site. The results indicated that improvement was necessary. In July 2003, a Web Redesign Task Force was formed to overhaul the Web site in order to provide a more dynamic and logical structure that would provide easier navigation and understanding. The task force was under the time constraint of having the new pages revamped by the beginning of the fall semester. The new library Web site was launched in September 2003 without further site analysis. Most users seemed to like the new site much better than the old one. A few public service staff reported that some of the users were confused and were unable to find information. As a fundamental part of the University of Mississippi Libraries’ mission is to ‘‘increase access to information and communication on campus,’’1 and as the Internet has become the predominant medium for the dissemination of library resources, it was essential that the adequacy of the new Web site be assessed, specifically the new home page. A Usability Survey Committee was formed to conduct a survey to assess the library home page as a part of the ongoing assessment of the library and its services. Certain criteria were established to determine whether the home page had met our goals of increasing access to information. Our benchmark for success was for at least 75% of students to be able to successfully complete each task. If the criteria for success were not met, the results would be used to improve the design of the page. The committee consisted of six faculty and staff members and began meeting in January 2004. As indicated by Nicole Campbell, a usability survey is ‘‘a method that tests how a user interacts with a system. The participant is given a list of pre-defined tasks to accomplish using the system and asked to dthink out loudT about their thoughts, reactions, and feelings.’’2 The committee decided to adopt this method as The Journal of Academic Librarianship, Volume 32, Number 1, pages 35–51 January 2006 35 an assessment tool in order to improve the library home page. In February 2004, a usability survey was administered to a group of twelve undergraduate students. Each student was asked to complete eight tasks as administrators observed and documented their actions. The tasks included both simple and more complex searches and included using the library home page, the library catalog, and databases from outside vendors. LITERATURE REVIEW There was not an abundance of literature discussing usability surveys as a form of assessment. We analyzed the existing body of literature from two angles. We selected a few articles that discussed facets of successful library Web sites and then turned to literature discussing usability surveys, their use, design, implementation, and effectiveness. The articles chosen were for the most part limited to academic library settings for more direct application to our survey planned for the University of Mississippi Libraries. As a foundation, select resources were consulted that highlighted elements necessary for library Web sites to be deemed successful. In one such article, Sandra Shropshire outlines her efforts to identify primary concerns that four medium-size academic libraries had regarding their Web sites. Shropshire found many concerns to be echoed at all four institutions, including a lack of enough staff to create and maintain an effective site and to answer patron feedback; the need for a library Intranet; the need for a designated back-up person in the absence of the systems librarian; the navigation of the when/why/how of redesign; and the integration of the OPAC with the rest of the site. Without these core elements in place, a library will not be able to meet users’ needs efficiently and effectively.3 Leo Robert Klein reminds academic librarians that Web sites are meant to serve the patrons’ information needs, not the librarians’. He contends that library users are busy, nonselective, and far more interested in finding their resource than in learning how to navigate a convoluted library Web site. He challenges librarians to embrace elements found in popular sites such as Google, as these are the sites with which their patrons seem to be most comfortable.4 Nicole Campbell looks closely at this issue as well and urges librarians to make sure that all of the hard work that goes into library Web site design and maintenance leads to a product that the patron can actually use.5 Before starting a usability survey, one must always ask: What exactly is usability? All academic libraries actively seek to have a streamlined, intuitive Web site for their patrons. Susan McMullen notes that distance learning programs and users’ remote access preferences heighten the need for self-explanatory Web sites, as there is sometimes not an opportunity provided for formal instruction. Some sites still prove to be difficult for new users and experienced users alike, failing to lead users through the pages to the information sought, and turning them off from the library Web site all together.6 Characteristics such as these, contend Elaina Norlin and CM Winters, are what make a site unusable. In order to ascertain if a library site is usable, the back-door approach of finding what does not work, achieved with a usability survey, proves to be far more fruitful than lauding one’s self on what does work.7 36 The Journal of Academic Librarianship Much of the literature emphasizes the amount of preparatory work required in the creation of a usability survey. In the National Institute of Standards and Technology Virtual Library redesign project in 2001, librarians consulted with focus groups to get verbal feedback on the site’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as consulting with a professional in the creation of their usability test design.8 Continually recording usage statistics for the site and noting the most used pages will help to identify areas on which to concentrate.9 From this information, librarians can derive specific, answerable questions for the survey that will illuminate gaps in test takers’ knowledge.10 Scripted recruitment and test dialogue ensures consistent testing,11 as does practicing test administration on an individual before performing the actual test.12 When dealing with the actual testers, a contrived crosssection of the user population is encouraged, as are incentives and a preconceived strategy for testing locations and structure.13 The body of literature indicates that shorter (half-hour) tests with a few specific questions are preferable to longer tests.14 According to Jakob Nielsen, libraries engaging in usability testing will achieve the best results when testing a small number of participants multiple times in order to reach the target fifteen test-user goal.15 Making sure that survey participants are comfortable is always a concern when conducting a usability survey. Several usability survey case studies that offer suggestions on this point are featured in Campbell’s Usability Assessment of LibraryRelated Web Sites. In a survey performed at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, student workers were used to administer the survey as a way to reduce intimidation.16 A survey performed at Arizona State University was administered in an empty office decorated with posters, plants, and items to help ensure privacy and a relaxed atmosphere.17 The literature indicates that across the board, testers employed the ‘‘think-aloud’’ method and acted as observers, recording qualitative measurements such as the test taker’s level of satisfaction with his answer and quantitative measurements such as the pathway taken to arrive at the correct Web page and the amount of time taken to do so. When Susan Feldman of Datasearch, an information system Web design company, performs tests on prototype sites for clients, she videotapes the sessions for later review.18 Fourteen students observed while doing personal research at Roger Williams University were tape-recorded while performing tasks in the think-aloud, observation/interview method.19 The literature we reviewed makes several points very clear: There are differing opinions on what made a Web site ‘‘usable’’; different opinions exist about how a survey should be administered; and the length of studies varied from institution to institution. All of the above literature helped us develop and administer a usability survey that fit our needs and goals. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES The goal of the usability survey at the University of Mississippi Libraries was to improve access to library resources through library home page by examining the way the undergraduate used the home page. The objectives were as follows: 1. to find out if students could find the basic library sources, for example a book, a journal article, a newspaper article, and personal account information, from the library home page; and 2. to see if 75% of the participants successfully completed various tasks using the most efficient number of clicks. METHODS Survey Design The survey administered to a group of high school students the previous summer was adopted as a starting point. Two of the tasks – locating a copy of Rolling Stone magazine and locating an article about Internet retailing in EbscoHost – were taken directly from the previous survey. The remaining content was modified based on input from reference librarians who deal directly with students and who had observed common problems with the home page. It has been noted that for a one-hour session, the survey should be limited to seven to ten tasks.20 Because we were working within a 50-minute time frame and knew that we needed to allow time for students and administrators to get settled, we chose to limit our survey to eight questions. Before it was administered to students, the survey was tested on a non-library user and adjustments were made as needed. We found that some of our language was too heavy on ‘‘library ease,’’ meaning that only librarians would fully understand the directions. When we asked our non-library user to locate a copy of The Catcher in the Rye, we realized we had not noted in the task that it was a book. As we specifically wanted the users to find a book, that detail was added. We also discussed whether we were telling students how to complete the task by using language used on the existing home page. If we asked students to find a subject guide, was that going to skew the results since the link was clearly labeled ‘‘Subject Guides?’’ We decided that in some cases we wanted to use terms used on the existing home page because we wanted to know if students understood what that term meant. On the other side of this issue, we asked students to find an article in Ebsco. The library’s Ebsco databases are labeled by their names, ‘‘Academic Search Premier (Ebsco),’’ ‘‘Business Source Premier,’’ etc. But both students and faculty refer to ‘‘Academic Search’’ simply as ‘‘Ebsco.’’ We wanted to know if students understood how to get to the databases page and if they understood that when they were looking for ‘‘Ebsco,’’ they were really looking for ‘‘Academic Search Premier.’’ Administrators Fifteen library faculty and staff members were recruited to administer the survey. Before the survey was conducted, administrators were required to attend a training session. Not everyone was familiar with the purpose of a usability survey, much less how to administer a survey. To achieve uniformity of survey results, administrators were trained on how to give the survey, what to say, and what not to say (see Appendix A). Also discussed were each of the questions and what type of comments and behaviors they were to look for and what to record. Students We debated how to recruit students. Going by Jakob Nielsen’s rule that with fifteen students you will learn what you need, we decided to limit our survey participants to fifteen undergraduate students. We wanted to have a crosssection of grade levels and looked at recruiting students through mass e-mails or simply asking for participants from students in the library. In the end, we did neither because of time constraints. We had to complete the entire survey in five weeks. This did not allow us the time we would have needed for recruitment. Instead, we decided to recruit the students from an existing library course. With the cooperation of the instructor, students from the class of Introduction to Library Resources and Electronic Research (EDLS 101) were selected for the survey. At this point in the semester they had not covered the use of the library catalog or other library resources. There were fifteen students enrolled in the class, representing every grade level. Only twelve students attended class the day of the survey. We discussed recruiting three more students to raise our number to fifteen. After looking at our results, we decided that we had sufficient information to assess the library’s home page. Since we used students from a scheduled class, we conducted our entire survey in a single fifty-minute period instead of administering the survey over several weeks. While this may not have been the ideal situation, it worked with our schedule. We were able to separate the students so that they could not hear or observe others taking the survey. Students did not know before attending class that day that they would be taking the survey, and each student was given four points extra credit for participating. The University of Mississippi requires any researchers using human participants to file for permission through the Institutional Review Board (IRB). The IRB required that we have each student sign a release form and be given the choice to not take the survey. The instructor of the class was a member of the committee and did not take part in the administration of the survey as she felt the students might feel uncomfortable or that they were being graded if she was involved. Each student was assigned to an administrator, and each administrator/student pair was assigned to a computer. Students were given a number after they signed the release. When they walked out of the library classroom they matched their number with the number each administrator was given. Administrators knew what their number was and to which computer they were assigned, which helped to streamline the process. We used office computers in the library’s Technical Services Department as well as one additional office computer and two computers in our computer lab. Each student was read a statement explaining the purpose of the survey and was reassured that they were not being tested (see Appendix B). It is not easy to make a student feel comfortable in a cubicle of a busy office, but we did what we could. Our administrators allowed us to use their cubicles and we were able to find some empty areas in the same office. We placed students in cubicles that would not be adjacent to one another so they could not hear the other administrators or students. We asked that personal items (pictures, notes, etc.) be removed from computer monitors and asked that the computer screens be set to the University of Mississippi home page, the starting point of our survey. We assigned three students to two other locations. Two students were assigned to our bibliographic instruction room. January 2006 37 Figure 1 Web Experiences Figure 2 The University of Mississippi Home Page (www.olemiss.edu). The Arrows Point to the Links to the Library’s Home Page. The University Libraries Link (1) Was the One Most Students Used; The Libraries and Museums Link (2) was Used Less, Although this Link Took the User Directly to the Home Page While the University Libraries Link Went to an Intermediary Page. The UM Home Page has Since Been Redesigned 38 The Journal of Academic Librarianship We placed them far apart and chose administrators with quieter voices in order not to disrupt each other. One student was placed in a private office with one administrator. This student took the longest to complete the survey. Whether this was related to his location or not was inconclusive. Measurement A student’s response to each question was scored by a number of quantitative and qualitative measures that included the number of clicks, the time it took to complete the task, as well as the administrator’s observation of the student’s action and his/her comments. Quantitative Metrics o Number of clicks to reach destination: a click was counted if it took a student to a different page. If a student went back to the previous page, that was counted as a click. If a student clicked a checkbox on a page (i.e., ‘‘full-text’’ box in EbscoHost), that did not count as a click. o Time required to complete the task: the amount of time it took to complete each task. had completed the task; average when a student thought he/she had completed the task but was not positive; and low when a student did not think he/she had completed the task. Qualitative Metrics Qualitative measures are based on the administrator’s observation and both the administrator’s and student’s comments. These included the following: o Signs of indecision: the administrator wrote down any indecision or hesitation observed in student. o Indications of frustration: the administrator recorded a student’s frustration when he/she started to grumble or mumble to himself or herself about the difficulty of the task. o User comments: the student’s oral observations, such as ‘‘the catalog page looks a lot like the home page,’’ or comments about what he/she would like to see, were recorded. o Completed the task (yes/no): if a student said that he/she could not reach the page, the task was not complete, even if they had indeed reached the page and did not realize that they had done so. o Observer comments: the administrator’s own observations and comments. o Satisfaction level (high/average/low): administrators were asked to rate high when a student was certain that he/she Before the survey began administrators asked students a number of questions ranging from their class and major to how SURVEY RESULT Demographic Questions and Results Figure 3 Students Were Confused By the Multiple Listings for The Catcher in the Rye, But Seeing the Author’s Name Listed in the Second Record Helped Some Students January 2006 39 Figure 4 The Students Who Found a Record for Rolling Stone in Journal Finder (TD Net) Misinterpreted the Record. They Thought the Library Only had it in Electronic Format Figure 5 When Looking for a Copy of Rolling Stone, Most Students Did a Title Search in the Catalog. Many Were Confused by the Results List. Not Seeing a Listing for Rolling Stone Magazine Lead Some to Think we did not Have a Current Copy in the Library 40 The Journal of Academic Librarianship comfortable they were with using the library Web page. This information was used to help us understand our survey participants. What Class are You? Our goal was to have an even representation of undergraduate class levels. More seniors participated than any other class level, but as a whole there was an even representation of undergraduates. What is Your Major? As with the class level, we had hoped to get an even representation of majors. In this survey business majors made up half of our participants. Approximately 25% of UM students are in the School of Business Administration, so our sample did not accurately reflect the make-up of UM majors. On a Scale From 1 to 10 (10 Being the Highest), How Much Experience Do You Have Using the Library Web Page? and On a Scale From 1 to 10, How Much Experience Do You Have Using a Web Site, Such as Google, to Find Information? The purpose of these two questions was to get a feel for how the students ranked themselves in using both the library Web resources and Internet search engines such as Google. This provided context when looking at survey results and what students felt their online research competencies were. The average ratings that upper and lower classmen gave for using the library Web page and ‘‘other’’ Web pages (Google, Yahoo, etc.) were similar. The lowest score given for searching the library Web page was 1; the highest, 8. The lowest for ‘‘other’’ was 2, the highest, 10 (Fig. 1). Survey Findings Find the University Library Home Page While we have little influence over the design of the University of Mississippi’s home page (www.olemiss.edu) (Fig. 2), we wanted to know if students knew how to get to the library home page; if a student cannot even locate the library home page it is not possible for us to provide any online services. Twelve out of twelve (100%) students completed this task; of these, ten were noted as being highly satisfied and two were at average satisfaction. No students were noted as having low satisfaction because all completed the task. The average number of clicks used to complete the task was 1. It took the survey creators one click. The least number of clicks needed to complete the task was one; the most was eight. Despite all of the students completing the task, not all of them found the library page easily. There were two links to two Figure 6 The Two Links Where Students Could Find the Library Hours (1 and 2). Before Finding the Correct Link, Some Students Looked Under Library Quick Links (3) January 2006 41 Figure 7 Nine Out of Twelve (75%) Students Were Able to Successfully Find the Course Reserves Page different pages on the UM’s home page: the ‘‘University Libraries’’ link went directly to the library site and the ‘‘Libraries & Museums’’ link went to an intermediary page with separate links to both the library page and the Museum page. Three out of twelve students reached the library page directly through the ‘‘University Libraries’’ link. One student began to do a keyword search on UM’s home page before he saw the ‘‘University Libraries’’ link. Another student immedi- ately clicked on the ‘‘University Libraries’’ and commented that she did that because ‘‘she knew it was the library Web page.’’ Eight out of twelve went through the intermediary page. One student did not realize the intermediary page was not the library page. The administrator said, ‘‘Please go to the library home page’’ when it became apparent the student did not realize that he was not at the library home page. Figure 8 Students had Problems with the Professor’s Name. Several Did Not Read the Instructions and Typed ‘‘E. Smith’’ Instead of ‘‘Smith, E.’’ 42 The Journal of Academic Librarianship One student clicked on the ‘‘University and Libraries’’ page and got stuck. He clicked back forth between the UM’s home page and the ‘‘Libraries & Museums’’ page several times before turning to Google. He found the library site by doing a Google search for the ‘‘Ole Miss Library.’’ Because of the two different links and paths to the library home page, we were not surprised by the results. After the survey was completed and the results tabulated, we did ask the university webmaster to make both library links go directly to the library home page. Does the Library Have a Copy of the Book, The Catcher in the Rye? Locating items in the library catalog was key to the assessment of our services. We wanted to know if students knew where to go if they needed to look up a book, and if they got there, if they could find one. Ten out of twelve (83%) were able to successfully complete this task, two out of twelve (17%) were not. Nine were highly satisfied with their results, two had an average satisfaction (meaning they thought they found it but were not sure), and one was rated at low satisfaction. The average number of clicks used in this task was 3.6 including those who did not complete the task. It took the survey creators four clicks to complete the same task. All of the students found the library catalog from the library home page. Two students hesitated at the home page before clicking on the ‘‘Catalog’’ link. The two unable to complete the task got as far as the title list in the ‘‘Catalog’’ (Fig. 3). When they got to the title list, they did not know which record was for the book. The Catalog proved confusing even to those who successfully completed the task. Like those who did not complete the task, those who did were confused by the title page but located the correct record. One student initially searched by author but quickly realized his mistake when he did not get any results. He was able to correct his initial search and successfully locate the record. The ‘‘Library Search Engine’’ (MetaFind page) was used by one student, but when it locked up he went to the ‘‘Catalog’’ and conducted a successful title search. Does the Library Have a Current Copy of Rolling Stone Magazine? This proved to be the most difficult task. Three out of twelve (25%) students were able to successfully complete this task; nine (75%) were unsuccessful. Only one had a high satisfaction rate with two average, and nine marked as Figure 9 Twelve Out of Twelve (100%) Students Were Able to Locate a Subject Guide by Using One of the Two Subject Links on The Library Home Page January 2006 43 low. It took the students an average of five clicks, that includes the number of students who did not complete the task. It took the survey creators two clicks through ‘‘Journal Finder’’ (TDNet page) and four through the Library ‘‘Catalog.’’ Students went different directions with this task. For their initial search, six went to the ‘‘Catalog,’’ one went directly to the ‘‘Library Search Engine,’’ one went to ‘‘Journal Finder,’’ and two went to the ‘‘Articles and Journals’’ page. We do not know the path taken by two students. Nine out of twelve students were not able to complete this task, six went directly to the ‘‘Catalog,’’ and two went other directions. Of the six who searched in the Catalog, two were successful in locating a current copy of Rolling Stone; four were not. Of the four unable to locate the magazine, two did not try another route. The two who did try a second route went to the ‘‘Articles & Journals’’ page where one tried ‘‘Journal Finder’’ but was unsuccessful, and the other student tried the ‘‘Library Search Engine’’ without any success. He returned to the ‘‘Catalog’’ and did a title search but only found Rolling Stone books. At this point, he stopped. One student went directly to the ‘‘Article Quick Search’’ (MetaFind) on the ‘‘Articles & Journals’’ page. Unable to locate the article, he went to the ‘‘Databases’’ page where he stopped. At this point he commented, ‘‘either I went to the wrong place or they do not have it.’’ One student skipped the ‘‘Catalog’’ and went directly to ‘‘Journal Finder,’’ where she was able to find a record for Rolling Stone. When she saw the TDNet record she said, ‘‘I guess it’s like EBSCO, not here in the library’’ (Fig. 4) (TDNet records indicate whether we have a periodical in print, online, or both). She either failed to see that it was available in print or did not understand how to read the record. The problems encountered with the ‘‘Catalog’’ were similar to their problems with The Catcher in the Rye task. They were confused by the title list (Fig. 5). Many students did a keyword search instead of a journal title search. One student did a journal title search and was still unsuccessful. He scrolled up and down the results page while mumbling ‘‘Rolling Stone magazine, Rolling Stone magazine. . ..’’ The first item listed was the record for Rolling Stone magazine; we can speculate that because it did not read the Rolling Stone magazine,’’ he did not click on it. This reaction to the title list was common. Three out of twelve students were successful in completing this task. Three went to the ‘‘Catalog’’ immediately; one successfully found the record. The second student did a keyword search and could not locate the record. The student returned to the library home page and went to the ‘‘Articles and Journals’’ Figure 10 Eleven Out of Twelve (92%) Participants Were Able to Locate Their Library Account Information From the Home Page. One Student Returned to the University of Mississippi Home Page and Looked Under Registration 44 The Journal of Academic Librarianship page without any success. After returning to the library home page a third time the student clicked on ‘‘Journal Finder’’ and found the record. Another student tried the ‘‘Library Search Engine,’’ and when that did not work he found the record in the ‘‘Catalog.’’ The different and numerous avenues students took to complete this task demonstrated their determination to find what they needed. They knew what the ‘‘Catalog’’ was and how to find it but did not always know how to use it. It was also evidenced that the ‘‘Articles and Journals’’ link was confusing. Students immediately went there but were not sure what to do when they got there. Or, they tried ‘‘Library Search Engine’’ but it would not work (we did find out later that this might have been due to some technical issues we were not aware of at the time of the survey). We initially assumed students would use the ‘‘Catalog’’ first and then ‘‘Journal Finder.’’ While they did use the ‘‘Catalog,’’ few of them noticed or tried ‘‘Journal Finder.’’ What are the Hours of the Library? This was one of the easiest tasks for our students with twelve out of twelve (100%) students completing the task. Eleven students were noted as having high satisfaction, one had an average satisfaction, and no students were marked at low satisfaction. There were two links to the library ‘‘Hours’’ page on the library home page: one in the main navigation bar at the top of the page and one in the blue side box. One problem we had with this task was that seven of the twelve administrators did not note which ‘‘Hours’’ link the students chose. We do know that three of the twelve chose the ‘‘Hours’’ link in the blue side box while only two chose the link in the top navigation bar. Three students showed some hesitation at the beginning of the task. Of those three, two initially went to the ‘‘Library Quick Links’’ drop-down box before seeing one of the links on the library home page (Fig. 6). When the student noticed the ‘‘Hours’’ link he commented that he ‘‘should’ve seen that [link].’’ One student, when asked ‘‘What are the hours of the Library?,’’ turned around and responded, ‘‘Seven to midnight.’’ Then he realized he needed to locate the hours on the home page. He immediately went to the link in the navigation bar. One general observation was that the most current hours were found at the bottom of the ‘‘Hours’’ page, such as special holiday hours or normal hours resumed. A reverse chronological order that places the most recent update at the top of the Figure 11 When Looking for a Full-text Article, Students Were Not Sure Where to Go First, Some Went Directly to Databases (1), Others Went to Articles and Journals (2). Those Unsure of Where to Go Clicked on the Library Quick Links Box (3). Some Students Used the Library Search Engine (4) But it Would Lock Up After They Entered Their Search January 2006 45 page was determined to be clearer, and this was fixed shortly after the survey was completed. Does Prof. E. Smith Have Anything on Reserve? This question was designed to see if students knew how to locate course reserves from the library home page through the ‘‘Course Reserves’’ link. Most faculty tell their students they have put an item on ‘‘reserve.’’ We wanted to know if students knew to go to the ‘‘Course Reserves’’ link on the library home page when looking for items on reserve. Six out of twelve (50%) students were able to complete the task; six were not. Three were highly satisfied with their results, four were average, while five had low satisfaction with their results. This task took students an average of 2.3 clicks; it took the creators two clicks. The results are misleading. Nine out of twelve were able to get to the ‘‘Course Reserves’’ search page from the library home page (Fig. 7). When searching for reserves by a professor’s name, the user is instructed to search by professor’s last name. Of the nine students who reached the ‘‘Course Reserves’’ page, three entered ‘‘E. Smith’’ instead of ‘‘Smith’’ or ‘‘Smith, E.’’ Of the six students who did complete the task, two did an initial search for ‘‘E. Smith’’ but realized their mistake, returned to the ‘‘Course Reserves’’ page, and searched under ‘‘Smith’’ (Fig. 8). Of those same six, three commented that they did not know course reserves could be looked up through the library home page. Six out of the twelve were unable to complete the task. Three of these six were the students mentioned above who located the ‘‘Course Reserves’’ page but searched under ‘‘E. Smith.’’ The remaining three were unable to locate the ‘‘Course Reserves’’ page. Two looked under ‘‘Contact a person’’ and one said he did not know how to do that and did not make an attempt. Suppose You are Taking a Class on a Subject Unfamiliar to You; Find a Subject Guide Relating to That Topic Twelve out of twelve (100%) of the survey participants were able to complete this task. There was very little if any hesitation shown by students. It took students an average of 1.6 clicks to complete the task; it took the creators one. Several students commented that it was ‘‘easy’’ or that this task was an ‘‘easy one.’’ Each student was able to locate the ‘‘Subject Guides’’ page and then chose a subject and clicked on the link to a subject guide. One student showed some hesitation after he was read the task. He looked over the home page and said, ‘‘I’m going to say dSubject Guides.T’’ Another student had no problem reaching the ‘‘Subject Guides’’ page. He chose the chemistry Figure 12 Students Were Confused By the List of Databases. Many Tried to Click on the Basic Search or Advanced Search Tabs at the Top of the Page But They Were Grayed Out. As a Result of the Usability Survey, This Page is Being Phased Out of Use at UM 46 The Journal of Academic Librarianship subject guide. When he reached the page for chemistry subject guide he hesitated. Judging from his body language, he seemed unsure. He scrolled up and down the page, noting the list of databases and Internet sites. When he reached the bottom and scrolled back to the top, he seemed satisfied he had completed the task. The library home page had two ‘‘Subject Guides’’ links: one on the main navigation bar and one in the main set of links in the center part of the page (Fig. 9). None of the administrators noted the path the students took. But by looking at the average number (1.6 clicks) of clicks it took students to find the subject guide, it was evident that they went through either of the two links on the library home page. This was one task where we questioned our terminology. By using the term ‘‘subject guide’’ in the task, we were leading them directly to the ‘‘Subject Guides’’ link on the home page. This question was loosely based on a question used in the usability survey conducted in 2003 and the same terminology was used. After some debate, the decision was made to use the term ‘‘subject guide’’ considering that it was not only the term used on the home page (which was out target of assessment) but also the term most likely to be used by both teaching and library faculty. How Do You Look at Your Library Account? A patron’s library account allows them to see what items they have checked out, renew books, etc. Being able to find this information will allow users to access their library information easier and faster. While it is not a new feature the University of Mississippi Libraries, we did not know if students knew it was available or if they knew how to find their information. Eleven out of twelve (92%) were able to complete this task; one out of twelve (8%) were not. Eight were marked as being highly satisfied, one had low satisfaction, and none were rated as average. Three did not have a satisfaction level marked for this task, but those three did complete the task. It took both the students and creators an average of one click to complete this task. Eleven out of twelve of survey participants were able to locate the link and the page where their name and barcode are entered in order to retrieve their library account information (we did not ask them to enter their personal information). Students commented that it was an ‘‘easy one’’ and said they knew to go to ‘‘My Library Account’’ (Fig. 10). Of the students able to complete the task, only one showed any sign of hesitation. This hesitation was caused when the student confused the catalog page with the home page. When he returned to the home page, he was able to easily locate the ‘‘My Library Account’’ link. One student was unable to locate his library account. When the task was presented to him, he commented that he ‘‘did not know’’ and that he had ‘‘no clue’’ how to find the information. He returned to the University of Mississippi home page and looked under the Registration link. This is another case where we may have found out more if we had worded the task differently. We know that a large majority of our students know how to find their library account. Does the same majority know that this is where they go to see if they have a book overdue or to renew a book? We can only speculate that because they knew how to locate their library account that they know what it is for. Locate a Full-text Article in Ebscohost About Internet Retailing This proved to be a difficult task. Five out of eleven students (45%) completed the task; six out of eleven (55%) did not. One student was classified as a ‘‘yes and no’’ because Ebsco timed out before he could get to the search page; therefore, the percentages for this task are based on eleven surveys instead of Table 1 A Task was Considered Success if 75% of the Participants Completed the Task Number Task Q1 Find the University Library Web page. Q2 Does the library have a copy of the book The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger? Q3 Complete Incomplete 2 out of 12 (100%) 0% 10 out of 12 (83%) 2 out of 12 (17%) Does the library have a current copy of Rolling Stone magazine? 3 out of 12 (25%) 9 out of 12 (75%) Q4 What are the hours of the library? 12 out of 12 (100%) 0% Q5 Does Professor E. Smith have any course reserves? 6 out of 12 (50%) 6 out of 12 (50%) Q6 Suppose you are taking a class on a subject unfamiliar to you, find a subject guide relating to that topic. 12 out of 12 (100%) 0% Q7 How do you look at your library account? 11 out of 12 (92%) 1 out of 12 (8%) Q8 Locate a full-text article in EbscoHost about Internet retailing. 5 out of 11 (45%) 6 out of 11 (55%) This table shows which tasks met our criteria. January 2006 47 twelve. The satisfaction levels, however, did not match up with the level of completion. Three out of eleven were noted to be highly satisfied with the results, two out of eleven were average, and six out of eleven were low. It took students an average of 4.1 clicks to complete the task; it took the creators of the survey three (Fig. 11). Of the students who did not complete this task, many experienced similar problems. Two students were confused by the EbscoHost Web page they had to pass through to get to Academic Search Premier (or any other Ebsco database). The list of databases was in no particular order and was confusing to students. Students that got stuck here tried to click on the Basic Search tab but it was grayed out. After scrolling up and down the page, clicking on grayed-out tabs, and reading definition tabs, one student finally commented that he had ‘‘no idea’’ how to locate an article. The other student stuck on this page said he was ‘‘looking for some place to type dInternet retailingT’’ but could not find one (Fig. 12). Another student bypassed the library home page and went directly to www.ebscohost.com. Because of the library’s subscription, the site recognized him as a subscriber; he was able to search using ‘‘Internet’’ and ‘‘retailing’’ as keywords. He got sixty-six results but did not know how to access the fulltext articles. One student never even tried. When asked to look for an article in EbscoHost he asked, ‘‘What’s that?’’ The EbscoHost Web page also proved confusing to those students who were able to complete the task. One student in particular clicked all over the page including the grayed-out Basic Search tab. She continued to click back and forth between the alphabetical databases page and EbscoHost Web. After reading the definitions of the Ebsco databases, she chose the Newspaper Source where she found an article. The ‘‘Library Search Engine’’ was another popular choice. Some students were successful and some were not. One student went to the ‘‘Library Search Engine’’ and searched for ‘‘EbscoHost.’’ After not getting any results, he searched for ‘‘Internet retailing.’’ He clicked on the fist result with ‘‘Ebsco’’ in the URL and was taken to an article in EbscoHost. When designing this question we chose to ask students to search in ‘‘EbscoHost’’ because most of their professors tell them to find articles in ‘‘Ebsco’’ as opposed to Academic Search Elite, Newspaper Source, etc. Students come to the reference desk and ask for articles from Ebsco. In addition to finding out if the library home page gave them enough direction to get to a database, we wanted to know if they associated any specific database with ‘‘EbscoHost.’’ We found that most knew what EbscoHost was because several Figure 13 The Redesigned Library Home Page 48 The Journal of Academic Librarianship told us they had used it before. It was the library site in combination with the EbscoHost Web page that caused confusion. The library is in the process of phasing out the EbscoHost Web page because of what we learned from the usability survey. CONCLUSION Because the usability survey was administered for our biennial assessment, we assigned some criteria in order to measure our success. For assessment purposes, the library home page would meet our goals of making library resources accessible if at least 75% or nine out of twelve participants would be able to successfully complete each task. The rate of completion ran from three out of twelve (25%) to all (100%) students, with five of the eight tasks completed by at least ten out of twelve (83%) participants. Table 1 shows which tasks met our requirements. Going by our criteria, we found users were able to successfully complete the directional tasks (Q1, Q4, Q6, and Q7) with at least eleven out of twelve students (92%) being able to complete these tasks. The more complex tasks (Q2, Q3, Q5, and Q8) proved to be more difficult. When students did not know where else to go, they were drawn to the ‘‘Library Quick Links’’ drop-down box and to the blue side box. We already knew students liked the blue box but we had always dismissed the drop-down box until we saw how much students used it. In general, there was a lot of confusion between the library home page and main ‘‘Catalog’’ page. On several occasions, students would stop at the ‘‘Catalog’’ page not knowing they were not at the library home page. Some issues raised by the usability survey have been resolved through Web design. We redesigned the library home page giving more prominence to the ‘‘Databases’’ and ‘‘Subject Guides.’’ We reordered the items in the blue sidebar box, and we plan on redesigning the page header to make the ‘‘Home’’ and ‘‘InterLibrary Loan’’ links more visible. We eliminated the ‘‘Articles & Journals’’ page and have begun working on a series of pages devoted to how to use the ‘‘Catalog’’ and ‘‘Databases’’ pages (Fig. 13). At our request, the secondary ‘‘Library & Museums’’ page has been eliminated. However, the UM home page has since been redesigned and an intermediary page between www.olemiss.edu and the library home page has been added. Some issues will have to be addressed by instruction—both in the classroom and at the reference desk. The survey showed us where we need to concentrate our instruction and in which areas students are having problems. ‘‘Journal Finder’’ is useful but many students do not understand what it is for or how to read the records. In conjunction with other committees, it was decided to purchase the MARC records for journals we have in electronic format. When students search for a journal in the catalog, they will get a record for both the print and electronic versions of a journal. ‘‘Journal Finder’’ will be phased out. Some areas of the ‘‘Catalog’’ are causing confusion. We have very little control over the design of the ‘‘Catalog,’’ but we know what areas to concentrate on during instruction sessions. A usability survey is a lengthy and time-consuming project. Like some of the studies done by other universities, ours was rushed due to the deadline. But the information we learned from observing our users using the library resources was invaluable. Looking back, there are things our committee knows now that we should have done differently, but all in all we feel it was a successful and worthwhile endeavor. Plans are in the works to conduct a follow-up survey. APPENDIX A. INSTRUCTIONS FOR ADMINISTRATOR Instructions for Administrator Be at Lyceum Circ Desk at 2:05 Bring A watch Form Number Pen/pencil Book, folder, clipboard Computer It should be set up and ready to go when you get there. A member of the committee will come around and check computers before you arrive. Survey Begins Read Script to your student. Time started: Time after you read script and before first question asked Time ended (on last page): Time last task completed While students are completing each task they will ask a lot of questions: ‘‘Is this right?’’ ‘‘Is this what you want?’’ ‘‘Did I spell this correctly?’’ You can’t answer their questions. Some possible responses to these questions: ‘‘Do you think it is correct?’’ or read the question again. They may also say ‘‘Is this what you wanted’’ when they get to the desired page. If possible restate the question. Hopefully, they will realize they are at the correct page. If after your prodding they do not realize they have completed the task tell them to move on to the next question. Quantitative Metrics Number of clicks to reach destination: The number of clicks listed after each question is how it was reached by one librarian. One click is considered a click that takes them to a different page. If they go back to the previous page, that is a click. If the click a check-box on a page (i.e., ‘‘full-text’’ box in Ebsco), that does not count as a click. Complete task: yes ____ no ____ If they get to the desired page they completed the task. If they tell you they can’t get to the page then they did not complete the task. Let them decide. If it is obvious they ca not figure it out, say ‘‘let’s move on to the next question’’ Satisfaction level: High ___ Average ____ Low ____ Was the student satisfied with the result. High: They completed the task and they know they completed the task. Average: They think they completed the task but they are not positive. Low: They did not complete the task or the completed the task and did not know it. Qualitative Metrics Signs of indecision: Use this to write down any indecision or hesitation you might see. If they point towards ‘‘Journal Finder’’ while looking for Rolling Stone and wonder if they should go there, make note of that here. January 2006 49 Indications of frustration: When the student starts grumbling or mumbling to him- or herself about how difficult something is, indicate that here. What did they say? When did they get frustrated? User comments: We are looking for student observations: ‘‘The catalog page looks a lot like the home page.’’ Or if the student makes a comment about what they would like to see, put it here. Observer comments: Use this area to write any comments you have while observing the student (i.e., for task #3 you might write: ‘‘Was confused by word dmagazineT’’). While these are your notes please understand others will be reading them. We do not expect full sentences but they do have to make sense. APPENDIX B. SURVEY FORM TIME STARTED: _____________________________ Administrator’s Name_____________________________ Script Hello. My name is _____. I will be working with you in today. Thank you for participating. The library has used its Web site to provide information for several years and we want to know if our Web site is useful to undergraduate students. In order to find this out, we want to watch how you and other undergraduates use the Web site. I will be asking you to do a set number of tasks. I want to emphasize that you are not being tested, and you are not being graded. While you are doing these tasks please tell me why you are doing what you are doing. If you click on a link, tell me why. It is okay if you cannot complete a task or find some information; there is no wrong answer. If you cannot complete a task, tell me why and we will move on to the next item. I will be taking notes on what you say and how you complete the tasks. Again, I am not testing you. Try your best to ignore me and everyone else in the room. While I am asking you to dthink out loudT as you are completing these task I cannot answer any questions you may have. Do you have any questions before we begin? Before we get started I have a few general questions to ask: What is your class rank? Class: Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Other What is your major? ________________________ On a scale from 1 to 10 with ‘‘1’’ being no experience to ‘‘10’’ being lots of experience, how much experience do you have using the Library Web page? On a sale from 1 to 10, how much experience do you have using a Web site such as Google to find information? 1. Find the University Library Web page. (One click from UM Web page) Quantitative metrics Number of clicks to reach destination: Complete task: yes ____ no ____ Satisfaction level: High ____ Average ____ Low ____ Qualitative metrics Signs of indecision: Indications of frustration: 50 The Journal of Academic Librarianship User comments: Observer comments: Please Return to the Library Home page Please wait one moment 2. Does the library have a copy of the book, The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger? (Four clicks from main library page) 3. Does the library have a current copy of Rolling Stone magazine? (Two clicks through Journal Finder; four clicks through catalog) 4. What are the hours of the library? (One click from main library page) 5. Does Professor E. Smith have any course reserves? (Two clicks from main library page) 6. Suppose you are taking a class on a subject unfamiliar to you (Chemistry, Telecommunications, Civil Engineering, Women’s Studies, etc.), find a subject guide relating to that topic. (One click from main library page) 7. How do you look at your library account? (One click to My library page) [They do not need to enter their personal data. We just want to know if they know to go to ‘‘My Library.’’] 8. Locate a full-text article in EbscoHost about Internet retailing. (Six clicks: four to get to Ebsco, two in Ebsco.) Thank you for your time. TIME ENDED:_______________________ NOTES AND REFERENCES 1. Assessment Record for Department/Unit of University Libraries, 2001–2003, Form B: Expanded Statement of Institutional Purpose Linkage, submitted 10 October 2003. 2. Nicole Campbell, ‘‘Usability Methods,’’ in Usability Assessment of Library-Related Web Sites: Methods and Case Studies, edited by Nicole Campbell (Chicago: Library and Information Technology Association, 2001), p. 2. 3. Sandra Shropshire, ‘‘Beyond the Design and Evaluation of Library Web Sites: An Analysis and Four Case Studies,’’ Journal of Academic Librarianship 29 (March 2003): 95 – 101. 4. Leo Robert Klein, ‘‘The Expert User Is Dead,’’ Library Journal 128 (Fall 2003): 36. 5. Nicole Campbell, ‘‘Introduction,’’ in Usability Assessment of Library-Related Web Sites: Methods and Case Studies, edited by Nicole Campbell (Chicago: Library and Information Technology Association, 2001), p. v. 6. Susan McMullen, ‘‘Usability Testing in a Library Web Site Redesign Project,’’ Reference Services Review 29 (February 2001): 7 – 22. 7. Elaina Norlin & C.M. Winters, Usability Testing for Library Web Sites: A Hands-On Guide (Chicago: American Library Association, 2002). 8. Susan Makar, ‘‘Earning the Stamp of Approval,’’ Computers in Libraries 23 (January 2003): 16 – 21. 9. Marshall Breeding, ‘‘Library Web Site Analysis,’’ Library Technology Reports 38 (May/June 2002): 22 – 35. 10. David King, ‘‘The Mom-and-Pop Shop Approach to Usability Studies,’’ Computers in Libraries 23 (January 2003): 12 – 15. 11. Barbara J. Cockrell & Elaine Anderson Jayne, ‘‘How Do I Find an Article? Insights from a Web Usability Study,’’ Journal of Academic Librarianship 28 (May/June 2002): 122 – 132. 12. Breeding, ‘‘Library Web Site Analysis.’’ 13. Janet Crum, Dolores Judkins & Laura Zeigen, ‘‘A Tale of Two Needs: Usability Testing and Library Orientation,’’ Computers in Libraries 23 (January 2003): 22 – 24. 14. Crum, Judkins, & Zeigen, ‘‘A Tale of Two Needs;’’ Makar, ‘‘Earning the Stamp of Approval.’’ 15. Jakob Nielsen, ‘‘Why You Only Need to Test With 5 Users,’’ Useit.com: Alertbox (March 19, 2000), http://useit.com/alertbox/ 20000319.html (accessed December 31, 2004). 16. Jennifer Church, Jeanne Brown & Diane VanderPol, ‘‘Walking the Web: Usability Testing of Navigational Pathways at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas Libraries,’’ in Usability Assessment of Library-Related Web Sites: Methods and Case Studies, edited by Nicole Campbell (Chicago: Library and Information Technology Association, 2001), p. 110. 17. Kathleen Collins & José Aguinaga, ‘‘Learning as We Go: Arizona State University West Library’s Usability Experience,’’ in Usability Assessment of Library-Related Web Sites: Methods and Case Studies, edited by Nicole Campbell (Chicago: Library and Information Technology Association, 2001), p. 20. 18. Susan Feldman, ‘‘The Key to Online Catalogs that Work? Testing: One, Two, Three,’’ Computers in Libraries 19 (May 1999): 16 – 19. 19. McMullen, ‘‘Usability Testing in a Library Web Site Redesign Project.’’ 20. Norlin & Winters, Usability Testing for Library Web Sites, p. 32. January 2006 51