The Courts:Keeping Speech Free in Troubled

advertisement

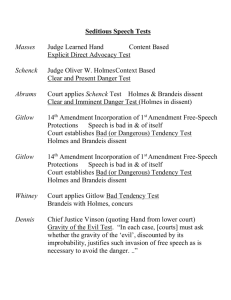

THE CORNERSTONE PAPERS A SERIES OF OCCASIONAL ESSAYS ON THE FIRST AMENDMENT No. 3 The Courts: Keeping Speech Free in Troubled Times John Corry T he First Amendment is quite definite: “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech….” Twice, however, in 1798 and 1918, Congress made laws that did just that, and while the 1798 laws were soon repealed or allowed to expire, the latter led to court decisions that still protect our right to speak freely. Indeed, in the ongoing battle to protect this right, the courts have provided our most formidable defense. Fortunately, that defense has remained strong in the aftermath of Sept. 11. Both the earlier and later sedition laws were inspired by fear of foreign intervention in American life; they were similar even in their wording. The Sedition Act of 1798 made it a crime to “print, utter or publish … any false, scandalous, and malicious writing” about the government. The Sedition Act of 1918 made it a crime to “willfully utter, print, write or publish any disloyal … or abusive language” about the government. Put aside now the question of whether the fear of foreign intervention was real or only imagined. The laws still overturned the most basic notion of a democracy: that citizens are free to criticize their government. PUBLISHED BY THE In 1919, only one year after the second sedition act became law, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled for the first time in its history on a free-speech case. The general secretary of the Socialist Party had mailed 15,000 leaflets urging opposition to wartime conscription, and been convicted under a law that made it a crime to “willfully obstruct” military recruiting. Oliver Wendell Holmes, who wrote the unanimous opinion upholding the conviction, agreed that there were indeed occasions when speech could be limited. “The most stringent protection of free speech,” he famously wrote, “could not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic.” But at the same time, Holmes set up a judicial barrier. Speech could be limited, he also wrote, only if it led to a situation that would “create a clear and present danger.” That same year, he amplified on what this might mean. When the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of four Russian anarchists for distributing leaflets that criticized capitalism and Woodrow Wilson’s war policies, Holmes dissented. He said the leaflets, which ended with the cry “Woe unto those who will CORNERSTONE PROJECT, A PROGRAM OF be in the way of progress,” posed no clear and present danger. Rather, he wrote (with what surely was a clear-eyed perspective), they were “silly.” Holmes’s views, and those of Justice Louis D. Brandeis, who usually joined him in his dissents, would in time dominate judicial thinking on free speech and also give it a structure. When Holmes wrote, for example, that the First Amendment protected the right to express even “opinions that we loathe,” or that “the best test for truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the marketplace,” he laid down rules that guide the courts today. In his written opinions Holmes took a more pragmatic approach to the law than did Brandeis. He also showed more skepticism about human behavior. Both justices championed free speech, although in calling for its protection, Brandeis was likely to appeal to loftier sentiments than would Holmes. Free speech, Brandeis believed, ennobled the people who practiced it; in showing tolerance for the expression of ideas they disagreed with they demonstrated their moral courage. In a dissenting opinion on the constitutionality of a California law to prohibit Communist and radical activity, for instance, he wrote this: “Those who won our independence by revolution were not cowards. They did not fear Free speech, Brandeis believed, ennobled the people who practiced it; in showing tolerance for the expression of ideas they disagreed with they demonstrated their moral courage. political change. They did not exalt order at the cost of liberty. To courageous, self-reliant men, with confidence in the power of free and fearless reasoning applied through the process of popular government, no danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and present unless the incidence of the evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is an opportunity for full discussion.” Meanwhile in 1925, two years before Brandeis wrote that, the Supreme Court had erected another barrier. It had accepted the argument put forth by the American Civil Liberties Union that it could apply the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment — “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States ... without due process of law….” — to free-speech cases. In other words, the Court could rule on whether state laws violated the guarantees of the First Amendment. This would be a great step forward in protecting our right to speak freely, but it should also be noted that the step forward came about in a case, Gitlow v. New York, in which the Court seemed to be moving in the opposite direction. The Court upheld the conviction of Benjamin Gitlow, who had been arrested in New York for violating the state’s 1902 Criminal Anarchy Act when he called for a Communist revolution. According to the Court’s majority, that did not necessarily lead to a clear and present danger, but it did suggest a “tendency.” In citing a “tendency,” the majority (no matter how well intentioned) was retreating into the past. The “tendency” or “bad tendency” doctrine was formulated in 18th-century Britain. By order of George III, laws were directed against the use of words that might have a “tendency” to create disloyalty, especially among men in the armed forces. The bad tendency doctrine lingered in Britain until the 19th century, although presumably it had disappeared in America with the adoption of the First Amendment, long before Gitlow. But radicals, whether of the left or the right, can awaken fears of subversion. Even if they commit no overt acts, unsettled times will bring about attempts to prevent them from speaking. Who knows what they might say, and what might happen next? As the Court majority ruled in Gitlow, words can lead to a dangerous “tendency.” But Holmes and Brandeis would have none of that, and as Holmes wrote in his dissent, the government could not penalize speech merely for “bad tendency.” “Every idea is an incitement,” he said, whether expressed by Gitlow or anyone else, and a free people must be allowed to express even the most subversive and provocative ideas unless, of course, they create a clear and present danger. The fear that the written or spoken word will provoke some kind of danger seems to underlie most attempts to regulate speech. And indeed, no thoughtful person can ignore the harm that words can do, or dismiss out of hand the idea that not all speech should be protected. The Holocaust was preceded by words that described Jews as less than human. Slaughter in the Balkans was facilitated by words that pit Serbs against Croats, and sometimes both against Albanians or Bosnians. Genocide in Rwanda became an acceptable act when a Hutu government demonized Tutsis. On the other hand, the right to speak or write freely is the most precious gift a democratic society can confer on its members. That right cannot be restricted for anything other than the most solemn of reasons. The urge to comfort the aggrieved, protect the vulnerable, or compensate for old injustices is not reason enough to dilute the First Amendment; neither is the desire not to see or hear anything distasteful or unpleasant, or inimical to our lifestyles or beliefs. But this is a lesson that must be learned again and again. New dangers from speech will always be seen. Standards of public morality began to change after World War II, for example, and in the 1950s the courts were asked to rule, for the first time in their history, on anti-obscenity laws. What was appropriate for public consumption and what was not? In the 1960s the Free Speech Movement on college and university campuses offered an answer. It insisted that anything goes. Meanwhile the courts grew reluctant to uphold anti-obscenity laws. The philosophy of the Free Speech Movement seemed to have won the day. In the 1980s, however, many of its old advocates moved away from “anything goes.” Certain words or phrases, and in some cases even gestures, or supposedly inappropriate sounds or facial expressions, were now to be forbidden. It was the beginning, of course, of the campus speech (or hate speech) codes. Speech code advocates wanted to protect whole classes of people from words that might make them uncomfortable, even if it meant contravening the First Amendment for the sake of political correctness. So speech codes proliferated on American campuses; students and faculty had to watch what they said, or perhaps even thought. In 1989, in the first speech-code case to reach the courts, a biopsychology graduate student at the University of Michigan challenged the rule prohibiting behavior that “stigmatizes or victimizes” individuals on the basis of individual characteristics. Such behavior, the speech code insisted, could create “an intimidating, hostile or demeaning environment.” The graduate student, who was also a teaching assistant, demurred. He said the speech code could prevent him from discussing the possibility that biological differences between men and women or among the races created separate personality traits The right to speak or write freely is the most precious gift a democratic society can confer on its members. and abilities (a position that would be anathema in the world of political correctness). What if, in a discussion, the graduate student or anyone else used words that offended men, women, or any member of a racial group? A federal district judge agreed with the graduate student and struck down the parts of the code that dealt with speech. Words in the code such as “stigmatize” and “victimize,” or “threat” and “interfere,” the judge found, were so vague that they escaped any real definition, and could be used to prevent someone from speaking freely. Moreover, the judge ruled that the university could not establish a policy to prohibit certain speech simply because the university “disagreed with ideas or messages” the speech sought to convey. Speech code advocates persisted, however, going back to the 1940s to find a legal justification. In 1942, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a Jehovah’s Witness in Rochester, N.H., who told a city official: “You are a God-damned racketeer … and the whole government of Rochester are Fascists or agents of Fascists.” The Court said these were “fighting words,” and that a person who used them could be punished if the words could “inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.” Presumably, then, a white student who uttered a racial slur against an African-American student in a one-on-one confrontation could be punished for racial harassment for using “fighting words.” But the University of Wisconsin used the “fighting words” defense to no avail in 1991. A federal district court pointed out that the Supreme Court had narrowed the definition of “fighting words” in the ensuing years and that the university’s speech code, which barred speech that created “a hostile or demeaning environment,” went too far; only speech likely to incite a breach of the peace could still be considered “fighting words.” The Supreme Court further eroded the “fighting words” rationale for hate speech restrictions in a 1992 cross-burning case. The Court ruled that speech could not be banned as “fighting words” if the ban were applied selectively based on the content of the words. Fighting words that consisted of racial epithets, for example, could not be singled out from other types of fighting words. In cases such as these the courts have stressed an overriding — and critical — theme: Speech cannot be banned simply because it is found objectionable by an individual, or even by large numbers of people. The First Amendment will not be jeopardized because of a fear of giving offense. The courts have since struck down other speech codes, and made clear that Holmes and Brandeis now dominate judicial thinking. In the face of threats to free speech that have arisen and will continue to arise — particularly in the wake of Sept. 11 — the Holmes/Brandeis legacy represents the First Amendment’s best hope. John Corry spent 28 years at the New York Times as a reporter, columnist, and editor. His newspaper career was complemented by a stint at Harper’s from 1968 to 1971. Mr. Corry was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard and a Gannett Fellow at Columbia. He also taught at Boston University. Mr. Corry wrote a media column for the American Spectator and is a regular contributor to Earth Times. He is the author of several books including My Times: Adventures in the News Trade. The Cornerstone Papers are published under the auspices of the Cornerstone Project, The Media Institute’s public awareness and education program celebrating the First Amendment. The goal of Cornerstone is to give the American public a renewed appreciation of the importance of free speech and free press. Activities of the Cornerstone Project include books, a luncheon series, public service advertisements, and a national symposium in Washington, D.C. The Cornerstone Papers will be published throughout the duration of the Cornerstone Project. For more information, contact The Media Institute or visit our Web site at www.mediainstitute.org/cornerstone. 1000 Potomac Street, NW, Suite 301 • Washington, DC 20007 202-298-7512 • E-mail: info@mediainstitute.org • www.mediainstitute.org