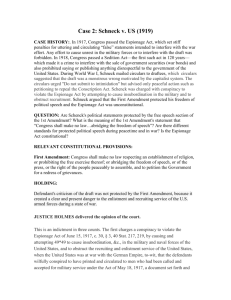

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919)

advertisement

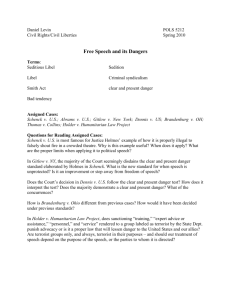

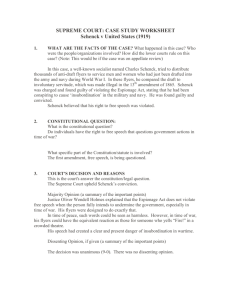

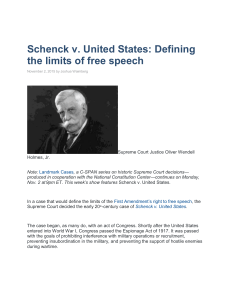

Charles Schenck, as the Secretary of the Socialist Party of America, was responsible for printing, distributing, and mailing leaflets to prospective military draftees during World War I, 15,000 leaflets advocated opposition to the draft. Contents included: "Do not submit to intimidation", "Assert your rights", "If you do not assert and support your rights, you are helping to deny or disparage rights which it is the solemn duty of all citizens and residents of the United States to retain," His rationale was that military conscription constituted involuntary servitude, prohibited by the Thirteenth Amendment. For these acts, Schenck was indicted and convicted of violating the Espionage Act of 1917. Schenck appealed to the United States Supreme Court, arguing that the court decision violated his First Amendment rights. Is defendant's criticism of the draft protected by the First Amendment? Does defendant’s leaflet threaten recruiting practices of the U.S. armed forces during a state of war? Does defendant’s leaflet violate the Espionage Act 1917? Defendant's criticism of the draft was not protected by the First Amendment Leaflets created a clear and present danger to the enlistment and recruiting practices of the U.S. armed forces during a state of war Conviction is upheld Principle of ‘free speech unless clear and present danger’ is established for future Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s opinion held that Schenck's criminal conviction was constitutional. The First Amendment did not protect speech encouraging insubordination, since, "when a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right." That is, wartimes permits greater restrictions on free speech Holmes sets out the "clear and present danger" test: “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.” “The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” Charles T. Schenck served six months in prison. Russian revolution, 1917 Eugene Debs (socialist leader) ran twice for the Presidency The IWW “Wobblies” and labor unrest Palmer raids German Bund and isolationists companion cases of Frohwerk v. United States and Debs v. United States did not mention “present danger”. Justice OW Holmes dissented in other convictions, 1920s Less restrictive "bad tendency" test adopted in Whitney v. California (1927) Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951), upheld conviction of communist party leader under the 1951 Smith Act, for (nonviolent) advocacy to overthrow US government Narrowed 1957: Yates v. United States restricted Dennis, ruling that Smith Act did not prohibit advocacy of forcible overthrow of the government as an abstract doctrine. But later narrowed by Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969) [KKK speech] › Replaced the "bad tendency" test with the "imminent lawless action" test › Ohio's criminal syndicalism statute violated the First Amendment, via the 14th, because it broadly prohibited the mere advocacy of violence. Holmes, dissenting in minority in the 1920s, had succeeded in defending free speech for the long term