Monetary policy without interest rates.

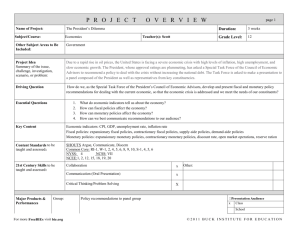

advertisement