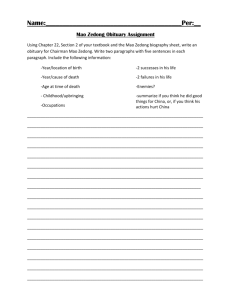

Between Destruction and Construction

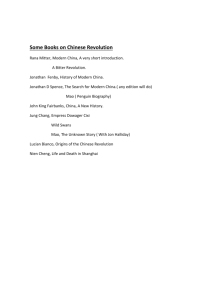

advertisement