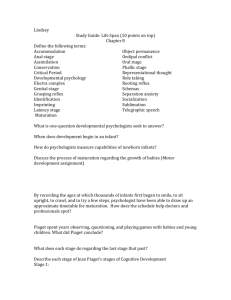

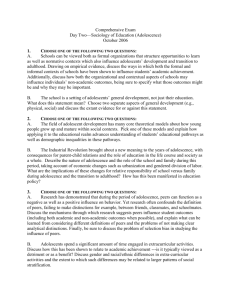

Adolescence, adulthood, and old age

advertisement