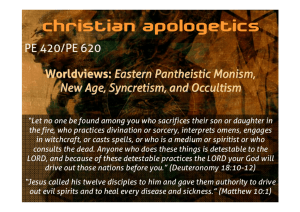

CHAPTER I: A Pantheistic View of Reality

advertisement