The Family and Culture - coursewareobjects.com

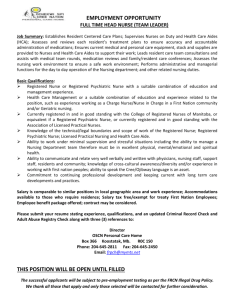

advertisement