2 - McGill University

/

THE MODIFIED AUTOKINETIC TECHNIQUE

A study of the development and change of norms

Irving H. Paul

Submitted to the Paculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of requireraents towards the degree of

Master of Arts

•Psychology Department

McGill University

Montreal

1950

CONTENTS.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sherif and the autokinetic effect . . . . 1

The nature of the norm . 4

The modification 7

2. EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

Apparatus 9

Subjects 11

General experimental procedure 11

3. EXPERIMENTS AND RESULTS 14

Psychophysical study .

.

.

.

.

.

. 14

Rationale underlying use of cloof . . 15

The cloof as a norm 20

The role of learning 22

The effects of after-images and seating Position 23

Conclusion 24

Sensitivity of cloof to a change in attitude or motivation 25

Group behavior in 'neutral

1

, cooperative, and competitive atmospheres 28

4. DISCUSSION

On the role of motivation 35

Conformity in the group Situation . . . 37

Further lines of experimentation . . . 38

Conclusion 39

5. SUMMARY

4 0

6. BIBLIOGRAPHY 41

--1--

INTRODUCTION.

Sherif and the autokinetic effect.

A widespread emphasis on the process of perception, in the understanding of social psychological and clinical phenomena, is currently foremost on the psychological scene. This orientation owes much to the pioneer experimentation and thinking of Muzafer Sherif.

Sherif's thesis, outlined in 1935 along with supporting anthropological data ,( 21 ), is that the way in which the individual perceives his world can serve as a fertile and reliable index of his behavior and its study would yield valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms which conditioning, or any response theory, probably never could.

As a suitable laboratory Situation in which to study social perception experimentally, Sherif adopted the autokinetic effect. (An adequate historical account of this perceptual phenomenon can be found in Adams ( 1 ),

Guilford and Dallenbach( 6 ), and Sherif( 21 ).)

The autokinetic laboratory design proved admirably suited to his purposes since:

1.) All one needs are a darkroom and a small source of dim light;

2.) Several individuals can observe the phenomenon at the same time;

3.) The Illusion of movement is easily induced after a

Short period of fixation;

4.) The role of the Visual field has been, to all intents and purposes, reduced to nil;

5.) The effect of past experience can be controlled, since it is very easy to find subjects to whom the phenomenon is new. This is not true of other judgmental methods that have been widely used, which include weight-lifting, color-constancies, literature, music, and so on( see p.5 ).

Sherif could thus crystallize out the social factors and study their influence on perception in a Situation uncontaminated by the influence of past experience and of the objective field. (For a discussion of f objective

!

and

f subjective f

in psychological thinking, see Schonbar( 20^ ).)

It was discovered( 21 ) that, in the autokinetic

Situation, the individual organizes his perceptions about some subjectively-adopted Standard. His judgments, as to the extent of the movement of the light during a two-second period, are not simply random but show a consistency that cannot be a function of the Stimulus since it, in fact, remains physically stationary. Individuais in a group each adopted a common Standard -- a social norm.

And a group of individuals, each of whom had previously adopted a subjective norm, exhibited a funnelling effect: their Standards converged towards a common group norm.

They conformed, as it were. A group norm was observed to

— 3 — persist, as a subjective one, after the individual was no longer part of the original group.

These findings, in context, are instructive and valuable. However, it is the sweeping manner in which

Sherif and others have been making use of them( 22,23,24 ) and the assumptions and biases which have thereby been brought into view, which prompted the modification, in the autokinetic effect design, which is the subject of this paper.

Sherif takes the long step from his laboratory

Situation into the »market place» in asserting that the processes, which the former has brought to light, are basic to the development and change of all norms and attitudes in real life. "They show..the basic psychological processes involved in the establishment of social norms.

,f

( 24,p.84 ) . In saying this, he clearly assumes that, basically, the clarity of the objective field plays no significant role in real life. This must follow since his experimental prototype entails the Virtual elimination of the Visual field. This bias, since it does violence to so many well-established facts, points to the serious limitations of the autokinetic technique, as designed by

Sherif, in teasing out the mechanisms which underlie the forming of social norms. Sherif himself admits that rf

..there is, indeed, the danger of the artificiality of

the laboratory atmosphere. The processes which we study..may have litble to do with the concrete way the norms work in actual social life.

M

( 22,p.68 )

That, in brief, is the basis of our objection and our attempt to alter the experimental method in order to render more valid the generalizations to the

»market place•.

The nature of the norm.

Even a cursory survey of the vast literature on judgmental behavior, dating back to the work of

Weber and the psychophysics of Fechner( 17,Pp.79-92 ), reveals that the phenomenon which we are discussing here is ubiquitous and basic in all behavior. It has been called by a variety of names -- set, attitude, value, frame of reference, Standard, norm, anchoring, expectation, atmosphere, and so on. Helson( 8 ) has recently attempted to describe this phenomenon quantitatively and subsume all the variety of its uses under the concept of

f adaptation-level f

. There can be no questioning its status in the process of perception.

The issue at stake here may be clarified by a brief outline of two possible approaches to the study of value which is probably the best example of a social norm.

~ 5 - -

The cultural-relativist takes the Position that the data of sense perception are neutral -- the objective field yields only »facta», the values being imposed upon them by the culture. "Social life may put the stamp of »right» or »wrong» on almost anything-or any object..

rf

( 22,p.126 ) . This approach is inherent in Sherif »s technique. The objective field in no way contributes to the norm.

An alternative orientation has been expressed by i/Vetheimer( 28 ) , Duncker( 4 ) , and Kohler( 10 ) and implied in the experimentation of Tresselt and

Volkmann( 26 ) , Lewin( 12 ) , Luchins ( 13,14 ) , and others.

Their thesis is, that in some cases at least, the objective field structure may irapose or dietäte the value judgment-value may be a datum of experience. For instance,

Lewin writes:

,!

0b jeets are not neutral to the child, but have an immediate psychological effect on its behavior; many things attract the child.."( 12,p.101 ) .

Without becoming involved in the thorny problem of value, a cursory appraisal of some of the major studies in judgmental behavior -- such as the work with weights by Wever and Zener( 29 ) , Hunt ( 9 ) , Helson( 8 ) , and

Woodrow( 30 ) ; with colors by Helson( 8 ) , and Hunt( 9 ) ; with drawings and rulers by Luchins( 13,14 ) ; with verbal meanings by McGarvey( 15 ) ; and with psychophysical

Stimuli by Pratt( 18 ) , and Woodrow( 30 ) — cle^rly

--6-support the thesis that the objective material plays, in a good many cases, a most significant role in the development of a frame of reference. Krech and Crutchfield

( 11 ) label these the »structural factors of Organization» differentiating them from the »functional» ones, and argue that "..whatever perception is being observed is a function of both sets of factors."( ll,p.83 ). Sherif himself writes that "..an important part of the social environment is made up of furniture that the child begins to see and use from birth, of tools he grows to handle, or melodies and rhythms..of proportions of buildings and trees, of sentence structure that is imposed upon him. .

I!

( 22,p.46 ) and "..hence, psychologically, norms are first on the Stimulus side in the genetic development..

,f

( 22,p.48 ), therefore "..it has for each individual who first confronts it, an objective reality.

,f

( 22,p. 125 ) so that "..in the initial state, norms may express the actual relationships demanded by the Situation."( 22,p.198 ) .

However his experimental paradigm neglects this aspect entirely.

The necessity of recognizing the influence of the

'facts

1

, even at a more complex level of normative behavior, has been dramatically illustrated in a recent study by

Stagner and 0sgood( 25 ). They investigated changing attitudes towards nations -- Germany and Russia — before and during the last war. They found that, although attitudes are certainly influenced by cultural factors,

"..»change they do», to some extent at least, with the compellingness of events.." even in the face of the culture.

- - 7 - -

The m o d i f i c a t i o n .

In view of the many m e r i t s of Sherif »s experimental method( see a b o v e , p p . l - 2 ) , we s e t ourself the task of modifying i t i n such a way so as t o make i t a b e t t e r p r o t o t y p e of the r e a l s o c i a l S i t u a t i o n . In view of the f o r e g o i n g d i s c u s s i o n , to do so must e n t a i l i m p l i c a t i n g the Visual f i e l d i n some d e c i s i v e way. How can t h i s be done?

The S o l u t i o n seem to l a y i n finding SORB way of g r a d u a l l y i n t r o d u c i n g a Visual f i e l d i n t o the a u t o k i n e t i c e f f e c t S i t u a t i o n . The norm which one could then study i s the amount of o b j e c t i v e frame of reference which the i n d i v i d u a l r e q u i r e s in o r d e r to d e s t r o y the a u t o k i n e t i c i l l u s i o n . This q u a n t i t y can, conceivably, be msasured along many dimensions, such as c l a r i t y , complexity, p r o x i m i t y , and so on.

A comparison of the norm which we use here and the norm which Sherif used( see above,p.2 ) i n d i c a t e s the g r e a t e r meaniingfulness of the former. Sherif admits t h a t the Standard which he used i s a " . . f r a g i l e , and i n a s e n s e , a r t i f i c i a l f o r m a t i o n . " ( 2 3 , p.229 ) .

One can s c a r c e l y contend t h a t s o c i a l norms and a t t i t u d e s a r e

e s p e c i a l l y c h a r a c t e r i z e d by f r a g i l i t y . I t i s t h i s s t a b i l i t y of norms to which Luchins r e f e r s in o b j e c t i n g to S h e r i f » s f o r m u l a t i o n " . . b e c a u s e t h e r e a r e s i t u a t i o n s i n l i f e i n which the Standards and the o b j e c t s of judgment are so c l e a r l y defined t h a t no s u p e r f i c i a l compromise i s p o s s i b l e . " ( 14 ) .

~ 8 ~

Murphy, Murphy, and Newcomb have stated the case clearly: "The social definition of reality is not the arbitrary imposing of subjective caprice; it is the fulfillment of one specific reality partly given in the material."( 16,p.218 ).

One may conceive of a continuum with complete clarity of Stimulus field at one extreme pole and the absence of all objective frame at the other.

Sherif operated at a point which was just about as close as one could conceivably get to this latter pole.

The present experimental design, if it works, could presumably investigate the greater part of the continuum and consequently enjoy greater transfer potential to the »real-live» social world.

--9--

EXPERIMENTAL METHOD.

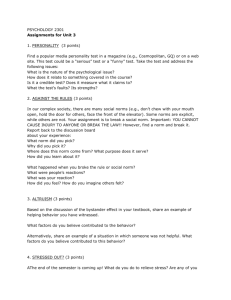

Apparatus.

A light-proof box was constructed out of plywood and painted black. Its dimensions: 18 X 18 X 36 inches.

Its front face had an aperture Q± X 5^ inches. In the front bottom corner, beneath the aperture (out of the subject»s line of vision), a socket was installed and connected to a variac( type 200-C 115v 50-60«g5a ) .

A sixty-watt bulb was used whose Illumination supplied the objective field by lighting up, first, the aperture, and, subsequently, the whole room. The reading on the variac served as a measure of the amount of Illumination at any time. 18 inches from the front; a cardboard partition, with a small hole,3mm in diameter,in its center, was installed in the box. Behind this hole a small light source was situated -- the autokinetic

Stimulus. The complete face of the partition was covered with a white sheet of drawing paper. This served to further dim the light and to prevent direct rays from striking the eye( see Adams( 1 ) ) .

The experiments were conducted in the »soundproof» dark-room in the Arts Building of McGill üniversity.

The subjects» chairs were placed about 10 feet from the front of the box. The experimentor sat behind them at a small, hooded table which held a small source of illumination, record sheets, and the variac.

— 1 0 —

V R o M T V i 6 v J

PIGÜRE 1 .

T H j c A o j o j < \ b 4 f c T I C ^QJL iHcer of

^ >

Bv^Tti=i

P A Q T \ T t O H . -

S \ O f c V \ 5 v J (>\<M.S C R o S S t C T i o w ^

? £ f l S ? £ C . T i V £ N / i S W

X H L _ J&*£ 5 ft-v*n £ fciXak & S 2 £3 o B

CjQf o

/

5-> tl

To? V \ t ^

. v. -..

l

.ll<

^ i1l1 y rr

^..^^

h r

3

^ \ O £ v/ * €. v^ i

^ c

—

1A

— 1 1 - -

Subjects.

A total number of thirty nine subjects were used; nineteen highschool students and twenty College freshmen and women. Eleven of the highschool students were candidates for their school basketball team (Montreal

High School). All other subjects were obtained on a volunteer basis. Most were strangers to the experimentor.

All phases of the experimentation reported were personally conducted by the writer.

General experimental procedure.

The subject, on entering the dark-room, is asked to keep his head and eyes down. He is led to his chair; the door is shut; the experimentor seats himself at his table making sure the hood is properly adjusted so that no light -escapes into the room; and then the subject is instructed to look up. After a brief adaptation period, the experimentor questions the subject to make certain that he sees nothing except the autokinetic light which has been switched on.

The subject is then instructed to report everything that the point of light does. When he finally reports that it is moving (and if he doesn't do so spontaneously, as most of our subjects did, it may be suggested to him) the experimentor then gives the following Instructions and questions (either all or any few, depending upon

— 1 2 — what data he's interested in collecting at the time):

1.) "Please teil me when the light stops and when it moves.

2.) "Teil me about how far it moves at a time.

3.) "Indicate the approximate direction of the light by using clock numbers. Por ex a mple,if the light moves straight down report

T six o»clock», and so on.

4.)

ft

What is the nature of the movement; smooth, jerky,slow?" and so on.

Then the light from the 60watt bulb is gradually brought in. At our variac reading of 25 the illumination was observed to be just sufficient to reveal the aperture.

It first appears as a hazy screen situated behind the point of light. When the subject reports the presence of this patch (and if he doesn f t he is questioned about it) he is further instructed:

5.) "I am still mainly interested in what the point of light does. You might ignore the screen completely.

6.)

,!

If the screen does anything interesting which you would like to report, please do so.

7.)

M

The point is eventually going to stop moving for good. Please report when it does so.

8.) "The point cannot move much less than about half an inch at a time. So if you see a movement of, say, an eighth of an inch or so, consider it as an illusion and don't report any movement. After all, it Is ten feet from you and it would be pretty difficult to see such a small movement at that distance, wouldn f t it? "

— 1 3 —

At every step in the variac adjustment a judgment is solicited if the subject does not spontaneously offer one. When he finally reports complete cessation of movement, a delay of between thirty five to forty seconds is allowed. If, at the end of this period, the subject still reports that the light has not moved, the reading of the variac is recorded and considered as the subject

1

s score. To make the numbers smaller and therefore

Statistical treatment simpler, 25 (the point of first visibility of any objective field) is subtracted from this score. This measure -- of the amount of Illumination needed, in the experimental room, to destroy the autokinetic illusion -- we have called the

!

cloof* (CLarity Of

Objective Field), for want of a better name.

Before repeating the procedure, the subject is questioned as to the existence of after-images. If so he is asked to look down until they have disappeared.

The procedure for a group of subjects is similar save for the fact that they are asked to prefix their Initials before rendering a judgment.

Other specific items of procedure will be noted in connection with the particular experimental requirements.

The experimental rationale for many of the above items of procedure will be examined in the next section.

— 1 4 - -

EXPERIMENTS AND RESULTS.

The experimental program that was conducted may be divided into two main sections: a systematic exploration of the psychophysical properties of our modified autokinetic effect method; and a study of the role of several experimentally-manipulated variables on our subjects' perception of the phenomenon.

Psychophysical study.

The modif ications which were made obliged the experimentor to produce answers to several questions:

Qu£sti£n_l_J It is known( 1 ) that lengthy fixation of a point under conditions of normal Illumination will eventually induce some autokinetic movements.

Consequently, how meaningful is our so-called cloof?

Is it, in fact, a significant threshold of some kind?

What is the nature of the transition from so-called

?

dark* autokinetic movement to afore-mentioned 'light* autokinetic, and what are the differences between them?

Question^^) If the rationale underlying the use of this measure is experimentally sound, does the individual show any consistency in his subsequent cloofs? Does he develope a norm?

Question 3^) What is the role of experience or learning?

Questi£n_4^) What are some of the other variables involved such as after-images, seating Position, and so on?

--15-gationale underlying use of cloof. In answer to the first question( see above ), several phenomenological observations are f l r a t

offered. A distinct difference is always noted between the kind of movement obtained in the dark and the type which one can get in the light.

The latter tends to be small, and jerky. It is extremely difficult to induce, requiring fixation periods of two to ten minutes. However the former is comparatively large, usually smooth, and is fairly easy to induce even in subjects who are aware of the fact that the light, physically, is stationary. In the light many subjects find it impossible to induce any movement at all, whereas nearly everybody gets the Illusion in the dark. These observations suggest a significant difference between the two phenomena and the existence of a threshold between them.

To experimentally validate these observations, two methods were used:

1.) Method_of_ j*s£ending a,nd des^ce^nding^sc^al^e^s :

Two cloof measures were determined for each of nineteen subjects. One, by gradually introducing and incre^sing the field Illumination; the other, by starting with füll illumination and gradually decreasing it. The former measure was determined by the cessation point of movement; the latter, by the point of initiation of such movement. The results are tabulated in Table 1.

— 1 6 - -

TABLE 1.

L

Wo. 6oC>tCT

1.

2 .

3.

•Ö.F. ft.n.

Gj.O.

H.

S.

_ 6.

H.

T.T.

G,-H.

1.

1.

9.

1.3.

Q.n.

L.R.

^ S C E W O I M C -

C L o o F

3

6

15

13 it

8 o

1H

2H

— i

CLooF

0 £ « , C 6 . M O I M G ,

Wo.

4\>fcifcCT

CLooF

1

8

IS

2 1

IM

7

9

M

21

/ / .

•2.

13,

X ? .

6.M.

A*£.

IM.

15. lt.

6.T.

A.tn, ft-F. m.D. 17.

18. F.\J.

19. 5.H.

6

4

«

15

IM

L s

2o

IM

OticeMPi»

M er * H-

«/ * 19

4

CLooF

' 6

4

<*

2 o

1 *

£ i"

| 6

15-

• 9 2

•

The high, positive correlation strongly supports the thesis that a true threshold is, in fact, being measured and indicates the reliability of the ascending cloof in measuring it. Ordinarily, a point between the ascending and descending threshold would be used as our estimate, but, since this would correlate so highly with the ascending cloof, and the descending method is complicated by after-images( see below p.25 ) , we thought it advisable just to use the ascending method in ascertaining the threshold.

— 1 7 - -

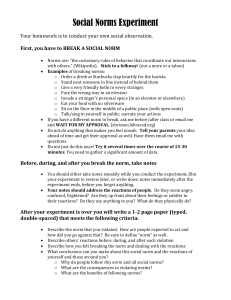

2.)_ RelatlngJLaten^yjpertod to_cloof ;

In Sherif 's studies( 21 ), if the subject did not indicate movement after a fixation period of 20 seconds, the light was shut and a judgment of 0 Inches recorded for that trial. The re a son for the size of this latency period is not given. The present experimentor found that the cloof was being based on a period-of-no-movement of about 30 seconds.

To deterraine the validity of this figure, and therefore of the cloof

a s well, six subjects were individually studied in the following way. First, his cloof was determined in the regulär fashion( see above: general procedure ) . Then he was asked to cover his eyes with his hand; the variac was set at a certain reading. At the signal

f go

!

, the subject removed his hand, fixated the light, and reported tnow* as soon as it started to move. This interval was clocked and recorded; the subject covered his eyes; the variac set at another reading, at random; and the procedure repeated. Latency periods of greater that one minute were not used since they are taxing for the subject and not necessary for our purpose^which was the

Validation of the 30 second period.

The results are tabulated in graphic form.

—18—

PIGUKE 2 .

V»

/

^ ho

^ Ö A P r i S S w o W i M q R t L A T i O N i S H l P o r L ä T e ^ C l 9 E Ö I O D T O ILLO^INOTION,

I. M . L . 2. tn.u. 5, F.ft.

H. P - 6 .

. o

0

0 u o

0 o

/ o r o o

z

: A~

\r

$

J o

O J 2 . 3 H S 6 O 1 2 . 3 HS" O 7 2 3 H 5 ^ O T T T H S T T H

S M . L . 6. M-L. 7. ß.F- 8- l.F. 1 . C.C m

2

O

6o

Vi

4£

2 u»

|S'|

- J O o

2 . 3 M o 1 2 . 3 4 o o i 2 3 o Q i 2 *3> o o Z - 5 ^ S 6 n ^ ° \ lo. CC. II. c c .

*

#

< " " ^

| Q F 6

I S . ß.Q. IH.HJT. &•<*.

O

4> tu i* h

So

/Xi

_ L

3 ~ T T 3 H S- 6 o | H M S" 6 7 S 1 / o "

0 i 2- 3 M ^ 6 7 £ <? / °

— 1 9 - -

An examination of t h e s e f i f t e e n cases( see f i g . 2 ) r e v e a l s c l e a r - c u t r e s u l t s i n t h i r t e e n of them. Each shows a more or l e s s sharp r i s e i n the v i c i n i t y of t h e p r e v i o u s l y determined c l o o f . Cases 9 and 1 1 , the two e x c e p t i o n s , were s e r i o u s l y c o n s i d e r e d . They suggested t h a t a 30 second l a t e n c y period was not an adequate c r i t e r i o n i n every i n s t a n c e . As a r e s u l t , i t was i n c r e a s e d to about 40 seconds.

These r e s u l t s i n d i c a t e an answer to question one

( see above, p . 1 4 ) . The close coincidence of cloofs o b t a i n e d i n ascending and descending s e r i e s ( r=H-.92 ) i n d i c a t e s t h a t some s o r t of t h r e s h o l d i s being measured.

The sharp r i s e of the l a t e n c y period p o i n t s to a s i g n i f i c a n t d i f f e r e n c e between the phenomenon in the dark and in the l i g h t . I t i n d i c a t e s t h a t t h i s t r a n s i t i o n i s a sharp one, and one which our cloof approximates r e l i a b l y .

Phenomenological reports strongly corroborate these conclusions. Twenty nine of our subjects were able to make definite statements, such as:

,f

Yes, I

!

m sure the light has now stopped for good." Only four appeared confused and indefinite, consistently prefixing their judgments with:

rt

I think..

rf or "It seems to me.."

It may thus safely be argued that the rationale underlying the use of the cloof is experimentally sound.

«20«

The cloof as a norm. Does the individual develope what might be construed to be a norm — a consistent way of organizing the Situation? This would presumably be manifested by a particular amount of objective frame of reference, peculiar to the individual, needed to destroy the illusion. A consistency of cloof, both during one experimental session and over a period of several, would be evidence of this norm.

A group of four subjects was intensively studied.

They were first put at their ease and impressed with the fact that they were assisting the experimentor in a simple perceptual experiment. Then about twenty cloof measures were taken for each individually over a period of two or three days. (It is important to keep in mind that in a cloof of, say, 6, the same number of judgments are involved, so that twenty cloofs can entail up to a

120 judgments or more.)

TABLE 2.

6QKSZCT c.c.

M L .

£

C. L.

O O F

1 S 'M 5 L

|i i . i n 1.

( ' 1 M I 1 1 • 11 in.ifcd.

8 9 lo \ //

IA*

o o o o 2. !

ei \ 3 1 7.

• H

8 j 4 o o l o

*W& vn.

T~l

BS £12

2° 7-2

'12. 19

5 2 8 3 5 o o 7o

23

L.n. •f J o o o

* I H ! 3 IH2 8-9

:££.<:* « Ho\ 44^xi l

-.2?u N = 7«

-r i \ i w j S O ^ C E fr;f> OF Sf>vlflg6*j ^••IrffWHOHC.6 E S T . n f l T f c

VJ l T H I »J

T°T« L VM

0

»- H

5

7t

-79

2 . 7 • * ;

II III . I I M l »

<?•*•

+ •7^

«21—

The fact that the between-groups sum of Squares is significantly greater than the within-groups sum

( see Table 2 )indicates the internal consistency which is our criterion for a norm. The within-groups variance may be interpreted as an error variance since it is so small and the reliability coefficient so large.

To lend further support to this conclusion we may refer to data yielded by the intensive study of eight high school students ( see below p.28 ) . Although the experimental Situation differed from the one just described ( see above p.20 ), nevertheless the same pattern is evidenced in Table 3 as in Table 2.

TABLE 3 .

SvQTECT JCV

^.x

Ix*

S-F. 21 lo6>

T.P.

JlL

AM 2<oS

. . . . . fc.U.

\

13 2% lofc f*2

H

I

R.C

V

2% O i 5 185-7 g

2<? l o ^ 6 oi 4 PJL s.t. 22. i

H o j l H o { 2

N-.tqS %.$**<li8 %t*\-\\oX f e t t e s > n of icoflftes • A-C

I.37&.S

......,

J^-7 - si

7-f

1

* n i i

1

- • i i i

2 7 ? |.o m

1 4 - 3 4 • <> o

^ - \ -

5

£>

« 4 - . M 8

J

. .

.1 1 • 1 . 1

« 2 2 «

Our subjects established a ränge and grouped their cloofs fairly symmetrically about the mean and median,

üherif( 21 ) reports similar results. However, he used the median to represent the norm. "We have found it more advisable to use the arithmetic mean of the cloofs, since most of our norms are determined by four or five cloofs.

The mean difference between the means and modes of

Table 2 and 3 is .8 .

The role of learning. In later sections we shall be concerned with demonstrating shifts in norms which we shall attempt to show are due to our experimentallyinduced variables. It therefore behooves us to show, first, that no consistent shifts occur as a result of the effects of repeated exposure to the Situation itself. To do this, we may call upon some test-retest data collected from 19 subjects, 10 of them, on consecutive days.

TABLE 4 .

So^Teq E* "5 T .

j e . ; n .

:

s.

t

LmB^n,L

: cc.\e.H^fAf.^

[

ntiL s , * < J L S . CT

T f r V T

ME£±I

iq 8-sU-f <H ' i !«-r 8 l M 3 is 6 \IH U \iS ? s" 2 n pl • : :

IM q j 6 U 2 U -t&io 'JBsiz. \i*H jip H ig i q \6 i H-2

F., i i . I M .im 1 — — — • 1 • « • • 1 = 1 __j j„ ^ .

2-S

«•I

The data indicate no consistent shifts which could be a function of training.

— 2 3 «

The effects of after-images and seating position. The presence of after-images must be controlled. These often exist when, after having introduced some illumination to determine the cloof, this Illumination is extinguished in order to repeat the procedure. "Do you see anything besides the small light and uniform darkness about it?" is the question we always asked after each trial. If the subject answers in the affirmative it is necessary to wait until they have disappeared. The experimentor

!

s personal observations are that these Images, though often very interesting, play havoc with the autokinetic movement, increasing it and making it erratic.

Since as many as three subjects were to participate, as a group, In perceiving the Situation at the same time, the effect of differential position had to be examined.

Due to the fact that the autokinetic light is situated

18 inches behind the aperture ( see above fig.l ) , it is seen from various positions, as located in different parts of the rectangular screen. It seems highly probable that proximity to the boundaries of this screen constitutes a dimension of clarity of the objective field. It,therefore, must be controlled.

Three chair positions were chalked-down( see fig.l ) .

They were so placed that our average subject saw: from position A | J from position B | * J from position C | ' I

« 2 4 —

The assumption was made that no significant difference exists between positions A and B. Whether any difference could be found between these two and position C was ascertained by testing 9 subjects from both of them.

TABLE 5.

SOR:F.CTS

T H E CLOOP

f ^ o n TvJo^eATjhjc^ Po*ir»o*s.

• i T " . ' " " T — ' •'

.£.....' 7 12 L QJ.

\ 7 i J U 7

;

1*1 J er i Sc 1 fffto^ C

The negligible inter-mean difference and the high correlation-coefficient, notwithstanding the small N, are fairly sufficient evidence that the role of seating

Position has been controlled. In addition, subjects kept their original places during the course of an experiment so that cloof-shifts presumably cannot be aecounted for in terms of the positions.

Conclusion. We have shown that the rationale underlying the use of the cloof is sound; that a norm is, in fact, developed; that experience plays no significant role in cloof-shifts; and that seating position has been controlled.

The foregoing psychophysical investigation is admittedly sketehy. Since the modification was designed to enable fruitful use in studying social-psychological phenomena, it was deemed wiser, before expending energy and time in carrying out an intensive psychophysical investigation, to determine whether the technique was sensitive to these psychological factors. If the following work proves valuable, in supplying useful Information and experimental leads, it

will then be in order to make the aforementioned investigation.

— 2 5 —

Sensitivity of cloof to a change in attitude or motivation.

Two groups of high school students served as subjects in this study: eleven boys, fifteen to sixteen years of age each, who were candidates for their school basketball team; and eight fourteen-year-olds.

The basketball coach( Mr.R.Jonas, Montreal High

School )sent his candidates up to the psychology lab, after a practise, implying that he had been requested to supply this experimentor with a group of subjects for an experiment. No connection to athletics was at all suggested, nor, as learned in subsequent questioning, was any suspected by the boys. After their cloofs had been determined -- individually, in a casual, impersonal atmosphere — the coach, who was of course our »confederate», informed the subjects that the test, which they were given, was a new measuring device for athletic aptitude which was currently in extensive use at McGill's physical education department. Since the boys already had a fairly good estimation of each other's abilities and chances of making the team, they were told that the test measures, not only the subject's current athletic prowess, but, more important, his potential for improvement with training and pr a ctise. The coach pretended that the results were to be used in Screening the candidates. He then informed them that his report

— 26 — of their scores was extremely disappointing, only very few of them having been at all successful. A short discussion period led to the decision to give the boys

»another crack at it f

, and back they trooped to the laboratory. The experimentor repeated the above

f tale f to the subjects. Nowhere in the procedure was any hint dropped as to what might constitute a »better

1

score except that reporting movement when the light did, in fact, rnove counted in one's favor, and so on. Then their cloofs were again ascertained.

TABLE 6.

—

" R E S O L T S D 9 noTiVATf;0.

S U & J E C T S .

M I

3VT. «n.S.W.C.?. ft-f. l.B. L.i<.T-Ot JB. X A v>.z. er pRfc-iisicemwE CLOOP

2l »5 tf // lS >2 |<?

2H /£ l9 /6 l^ovr-INC eNTWe. Cloof

IS" 1 ' H

1

7 i // 6 ! 7 i 9 i 12 M

^ ü i t £ ^ n

ö f -So^Aaes cl-6 Vf\^\«hace E£Tim*iT£

^

5.o

/

(±&*b>?J>

V \ T r t » M

G^eou>p^

[ T O T ^ U 1

2 5"5". o

< T 3 / . H

2 o !

Zi \

X

I 7 J lo.o

\Z.1S* S \ j

«s^c-f. a t . 0 0 1 l e o e l .

« . . j

Upon questioning, all subjects reported that they trled much harder the second time. None of them admitted belng very exclted or emotional —"..just a bit.» and only one expressed suspicion concerning the relationship of seeing a light move around to athletic aptitude.

— 2 7 —

The second group of high school students was studied in connection with work reported on page 28.

The data that concerns us here was obtained by first determining each subject f s cloof in a casual, impersonal, and relatively unmotivated atmosphere and, after this, telling them that the test is really a highly reliable measure of some aspect of intelligence. They were impressed with the fact that this kind of

!

intelligence

} doesn f t manifest itself in school marks. To heighten the motivation, a prize of tickets to a hockey game was offered to the winning subjects. Again the criterion for a good score, which is given, in no way informs the subject whether he has been seeing too little or too much movement.

TABLE 7.

S v j & a e - C T S . T . f . S - E . F . B . S . P , X s . £ , H . G . o , R . G K X

M-7 pDtT-lMCBMTt/ft CLOof 1 / £ . H S- S [ H 8 S-3

12-r

S-6

2.4

8 t %\

Q4ow?5

TofflL

2 4 C

€\?> i i£J

'S \ av% \ f . ftt « O l

Uoe l.

Combining the d a t a from Tables 6 and 7 ( N=19 ) u y i e l d s an F - r a t i o n of 24.6 which i n d i c a t e s t h a t the mean of the ' p r e - i n c e n t i v e f c l o o f s ( 14.8 ) i s s i g n i f i c a n t l y g r e a t e r than the ' p o s t - i n c e n t i v e

!

m e a n ( 6.9 ) a t the .001 l e v e l

This downward s h i f t may s a f e l y be construed to be r e l a t e d to t h e S t a t e of m o t i v a t i o n or the a t t i t u d e which our e x p e r i m e n t a l procedure induced.

— 2 8 —

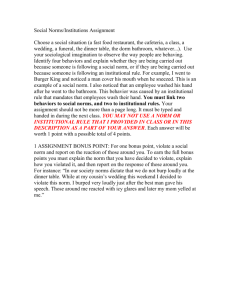

Group behavior in N e u t r a l

1

, cooperative, and competitive atmospheres.

Sherif

?

s main findings( 21 )consisted of strong evidence that, in a group Situation, individual norms tend to

f funnel

?

towards a common social norm.

The situations were all motivationally »neutral

1

and the norm studied, a "fragile one"( see above,p.7 ) . i/Ve wished to learn how the cloof behaves in vari ous group situations.

Our group of eight fourteen-year-olds served as subjects. They were first told that the study was a simple perceptual test and then each was examined. In several subsequent periods they were tested in groups of three —

f

'..to save time, you see."

PIGURE 3 . l M O W \ f } U < M A Y

/ . iwc>»\/\o^«u>

2.

I M C ^ O J P o o o

1-s

/ ^ 3 H 5 G T 8 n r ^ \ Y=V *- ^

^ S M 5 ^ T 8 ^

3,

2o A i o w t

G^^ooP A L O N c

/ Z 3

/ £ 3 S * &

— 2 9 —

TABLE 8 .

R & S o l T < > Ö ? . *Jhi,rnpT\ 7ATF.O G i & o u P S . fefcfc i-\C n

.3.)

A y e R o c - j E .

C L O O P

O F O T H e d

G d o u P

J

I 2..- £

...

»

MiU.ÄJil.Jiui.'H..

1 .. ' ajumr

Z.

/o M-S-

3

I .3

/£

8

9

3

12-

/o

11

:£= lo.S"

/ /

~ j -

X--II

H

0 - - 5

*AlOMfc~* "*!* G,SU>w>P n o t s»^""»-

The amount of shift that occurred in the group

Situation is insignificant. Nevertheless, its consistent direction, in seven of the cases, towards the group cloof, indicates some degree of funneling. That the conformity is slight is indicated by the fact that the average discrepancy between the S's cloof in the group and the group's cloof is 2.5 while the mean shift is only 3.0.

The small N makes this equivocal data useful only insofar as it suggests that conformity may not be the rule in the development of social norms. Further exploration here is called for.

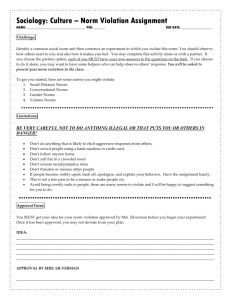

Pollowing this, the subjects were informed that the test was not simply a perceptual one but, as described above( p.27 ), they were led to believe that it was a measure of a desirable trait. The group was then divided into four teams of two. The experimentor teamed up those individuals whose cloofs were most similar. A pair of tickets

— 3 0 — to a p r o f e s s i o n a l hockey match was offered as a p r i z e f o r the

f w i n n i n g

!

team.

The four p a i r s y i e l d e d twenty s e t s of o b s e r v a t i o n s

( one s u b j e c t took i l l ) i n which the members of the group were i n c o m p e t i t i o n .

PIGURE 4. h

2

0

IL

0

0

J o

°l

?

7

1

z

S

M

3

X i o

Z^

/

' 2. 3 M

• #

7

\

A { M w A l _

9

L

\

\_ /s

^ X ^

W

\

.

/

\

/

• _ - •

« „ „ » . ^ • <#- #

19

^ • s

17

* — •

/S

k-" "•

•

15"

• — - •

\ \

/ o

• — • -

X * \ difiLS

— 3 1 —

Examination of fig.4 reveals two clear-cut cases of funneling; 7 and 10: four, which might conceivably be interpreted as such; 5, 8, 9, and 18: and fourteen which cannot be interpreted as illustrating conformity.

In fact, in cases 1, 3, 4, 6, 11, 12, 14, 15, 19, and 20, there appears the inverse of funneling — a tendency for the first judgments to be similar followed by progressive divergence. Table 9 shows this divergence to be significant.

TABLE 9.

1

J

7.

S

3

M.

S

G

7

8

5

/ o o

1 o o

S

S

o

0

Is. fi o

12

ß

3

M

H

IS H o

1?

Jt H

17 3

1?

LS

"i l

7 1°

4x 4 7

Z 2-5

—

T i l i <=>L.S

2. ^ M

Soo«.ce.

2- 4 5

A N A L H ^ S O F \/|gvft.nqKi c e.

6 ^ n » f & Q ^ « A £ ' S

%*>>z

JtÜL

5

ESTmoTg.

27-7 -Ab o 4 M

7o b~ 7

76

2. 2 H

3 1 I

6 1 1.3

O 0 o

ToTflL 7 i i i i 7?

F * - S ^ " = 2-9? Siy». at .OS l«v,«l.

£ g 2

1 0 3 i M T e R - n e f t M DiPfi-a£NC£,

<

;

Talmis i - 2

2 0 o lo |o 13 - "5 ZI

4 6> lo

7 5" H

S 5 lo

I - H

£•$

5" 3 5 \ g 3 9

2 - S

0 . 7

AVoT

4 2 4 2 All

3 2 i

5" 9 L i r 8 . <*

74 ? 2

| / O H

3 - M

m . J. Li • 11 1 1. .

..' . ,

•CS" J e j e i

5-7 H-/ 5".£

— 3 2 —

The Performance of each team-member with h i s p a r t n e r , presumably a c o o p e r a t i v e atmosphere, gave the following r e s u l t s .

FIGURE 5. isr ' . 2 . "5 • H

/ >

#.-~ #

^

•

0» +

I

6

Two of these sets of data cannot be construed to indicate funneling. Since the fact, that teams were grouped, in the first place, according to similarity of cloof, might conceivably account for the funneling evidenced in the other two sets 1 and 4 . some additional kooperative

T data were taken.

Two subjects, whose cloofs differed, were offered a pair of hockey tickets if their Joint effort surpassed a certain hypothetical Standard. The need for Cooperation was especially stressed to these two subjects.

FIGURE 6.

R E S O R T * OF noTiv/ATeo^ CooP€.kflT/*c

1

^ u % 3 £ . c r s .

<?

S

7

^ l> o r o H t

^r 4P W

Z 3 H S 6 7 ff 1 '

" T ß . o L S

--33 —

It is probably in order to introduce, at this point, part of some data later collected with College students.

One student was studied intensively over a period of several days. During this time an attempt was made to bring his cloof down simply by grouping him with confederates who reported, in a very certain and definite fashion, complete cessation of movement as soon as the aperture became visible( cloof of 1 ) . No motivational factors were experimentally involved. After a College student confederate had failed( see below fig.7 ) , a graduate student was used who pretended that he had been working on the same perceptual problem and using similar equipment "..down at Harvard.'

1

FIGURE 7 .

, • I

8 v x

' \ y^

/

• 9 -*»•&

3 t

04

Alone

• J

I t is apparent from fig.6 that the two motivated subjects did not succeed in funneling their cloofs.

Fig.7 shows that confederates were not successful in getting the subject f s Performance to conform with their own.

--34--

The experimentor noticed that two subjects may disagree constantly throughout the course of a trial yet their cloofs emerge similar. Since a similarity of cloof appears, superfieially, to illustrate conformity in every case and often serves to conceal a good deal of disagreement, the number of judgments in disagreement( one subject reports movement while the other, none ) and in agreement were recorded in all cases

Table 10 indicates these data for those cases, in figs. 3, 4, and 5, which exhibit funneling.

TABLE 10.

AftesemenT

F x G,. 2> l 2- 3 H a r m rt i5"

F i C v

4 lk 32 H I Z(o <? 4 % l \ s \ i

' j H 4*

3 \ (7 »67

.

....

/ 6 f l M

La.

Table 10 suggests that clear-cut conformity only took place in cases 7, 8, and 9 of fig.4; and case 1 of fig.o.

Conformity does not seem to be the case in cases 2, 3, and 4 of fig.3; and case 4 of fig.5.

Table 11 summarizes the group results.

TABLE 11. fv^NM B L.\ k)Gj

O l v / t ß - ^ I N ^ i V o i J c o K i F o ^ n ^ ^

U h J D P T v V ^ T C D lo

TOTAL

15

2

M

I!

15" l o o ^O

— 3 5 —

DISCUSSION.

On the role of motivation.

That the amount of objective field, necessary to destroy the autokinetic Illusion, decreases with a change in motivation can be interpreted in at least two ways.

One might argue that the need, which is related to the motivation change, affects perception directly.

This »behavioral ' factor should override the 'autochthonous* ones and the judgment be based more on the need than on the objective evidence( see Bruner and Goodman( 3 )).

This position has difficulties, with reference to our work, since the need which was experienced by our motivated subjects was simply

f

to do better

1

. There was no a priori reason to believe that this entailed seeing less movement.

Also, in seeing less movement it is the autochthonous factors which are dominant since, physically, the light does not move. Here is a Situation in which the need, instead of emphasizing so-called behavioral factors, stresses the autochthonous ones.

This writer prefers the second alternative. That, when motivated to do better, the subject makes more and better use of the amount of objective field available as well as actively seeking out more of it. That one may speak, without running the danger of doing so in animistic terms, about the individual striving to organize or

— 3 6 — actively attending, has been discussed by Hebb( 7 ) .

The second Interpretation receives support from the observations which were made of the types of behavior which took place when the motivational factors were introduced into the experimental procedures. At this point a great deal of

f

experimentation» was initiated by most of our subjects whereas they had carried out none previously in the unmotivated atmosphere.

Most typical were those instances of more simple

Experimentation

1

, such as: "When I move my head, the light moves."; "When I close one eye .."; "If I look at the side of the box the light doesn't move.";

"My eyes aren't moving — hey, I think I'm imagining it!" and so on. More significant yet are those instances of

r advanced experimentation

1

where, for example, the subject leaned over in his chair so that the autokinetic light became situated in a corner of the screen: "You can teil easier if it moves when it f s in the corner." he reported. Another instructive case: "I put my hand up to my eyes right under the light. i; try to keep my hand still and see if the light is moving in comparison."

A subject reported tilting his head back so that the light was

f

touching

1

the tip of his nose. The task then, of course, is to keep his nose still. One less scrupulous subject, it was subsequently learned, had been

— 3 7 —

'cheating' all along. In the dark, he had left his chair and quietly crawled forward to get closer to the light.

Several subjects tried to make use of their luminous watch-dials. Some developed 'hypotheses' about the nature of the mechanism which moved the light and operated the screen. "It seems to stay in the same place in the screen, so the light probably has to move when the screen moves, so

I'll watch the screen.." was typical.

All these behavior patterns may be understood as attempts to supply an objective frame of reference where none exists or to increase the usefulness of the available one. They suggest the relationship between our experimental design and problem solving. Considered together with the highly significant downward shifts in cloof, which, in our sample, bore not a Single exception

( see above Tables 6 and 7, pp.26 and 27 ), these behavior patterns serve as an index of the cloof's sensitivity to changes in motivation and attitude.

Conformity in the group Situation.

The thesis of Tresselt and Volkmann( 26 ) that persons tend towards uniform opinion by being subjected to restricted ranges of physical Stimulation as well as restricted ranges of social Stimulation, seems to have been borne out using the modified autokinetic effect technique.

Here we have augmented the ränge of physical Stimulation and conformity is in no way characteristic of the resulting

— 3 8 — data. Indeed, much of the evidence from our competing groups suggests that a progressive divergence takes place in that kind of social atmosphere( see above, Table 9, p.31 ) .

Those groups who were motivated both to cooperate and to do well did not display conformity either( see figs.5, 6, p.32 ). One might argue that here we have a conflict of motivations operating so that the results simply demonstrate the dominance of one over ther other. This view might be defensible were it not for the equivocality of the results from the unmotivated groups( see fig.3, p.28 ) along with the clear results from the unmotivated subject with the confederates( see fig.7, p.33 )

#

In these instances no incentives were experimentally involved, yet clear-cut funneling was anything but the case. Here, it may be said, we have pitted the objective field against social

Stimulation and have indicated the efficacy of the former.

To this we would subscribe, while contending that both are inextricably involved in the psychological field.

Further lines of experimentation.

One would want to know the effect of emotional disturbance both on the group»s behavior and on the individual

f s cloof when he is alone and when in a group.

Personality derangement might profitably be studied as well as the effects of brain damage, drugs, fatigue, and so on.

Work is called for in studying the group Situation.

Especially different kinds of group atmospheres; cooperative, competitive, unfriendly, relaxed, charged with emnity, and so on: and different kinds of groups; membership, reference, scapegoating, friendship, etc. The mechanism underlying

--39 — prestige-suggestion and imitation might be profitably studied. Bray( 2 )has recently attempted to validate several anti-minority-group attitude scales using the unmodified autokinetic method. It might prove of value to study the behavior of such

f mixed r

groups( bigot together with the object of his prejudice )In our modified Situation. Some of the shortcomings of Bray's work might thus be eliminated.

In view of the current interest in rigidity as an index of ethnocentricism( see Rokeach( 19 ) and

Frenkel-Brunswik( 5 ) ) , we might profitably use the present technique to study it. Rigidity might, conceivably, be related to size of cloof and ease of shift.

Conclusion.

Our subjects constituted a selected sample. That nineteen Montreal High School students behaved in a certain way, has been shown. We make no generalizations to the public-at-large. We believe such inferences to be indefensible under the circumstances. We have set out, in the first place, to study an experimental technique, not a population of individuals. We have tried to demonsträte that this technique works, and can prove useful insofar as it is congruent with a theory which is proving itself fruitful. We believe to have shown it to be a sensitive and reliable instrument.

— 40 —

SUMMARY.

A modification was made of the autokinetic effect laboratory method as designed by Muzafer Sherif. This modification was devised in order to implicate the objective field.

A box was constructed which permits the gradual illumination of the Visual field around an autokinetic

Stimulus. A variac reading yields a measure of the amount of objective frame of reference. The amount, which is required to destroy the autokinetic illusion, we have labelled the »cloof'( CLarity Of Objective Field ) .

A psychophysical investigation reve^led that the rationale underlying the use of the cloof is experimentally sound; that the cloof is a reliable estimate of an adaptation-level; and that learning, per se, plays no significant role in cloof shifts.

It was found that changing the state of motivation or attitude, by introducing incentives, resulted in a significant decrease in the cloof.

Conformity was found not to be the rule in neutral, competitive, and cooperative group atmospheres.

Phenomenological data support the thesis that motivated subjects actively strive to make better use of, or to create, an objective frame of reference.

Nonconformity is seen related to the widened ränge of physical Stimulation.

— 4 1 —

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

1 . ADAMS,H.F. A u t o k i n e t i c s e n s a t i o n s . P s y c h o l . M o n o g r . ,

1 9 1 2 , 1 4 , N o . 5 9 , 1 - 4 4 .

2 . BRAY,D.W. The p r e d i c t i o n of b e h a v i o r from two a t t i t u d e s c a l e s . J . a b n o r m . s o c . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 5 0 , 4 5 , 6 4 - 8 4 .

3 . B R U N E R , J . S . , a n d GOODMAN,C.C. Value and n e e d a s o r g a n i z i n g f a c t o r s i n p e r c e p t i o n . J . a b n o r m . s o c . P s y c h o l . ,

1 9 4 7 , 4 2 , 3 3 - 4 4 .

4 . DUNCKER,K. E t h i c a l r e l a t i v i t y ? ( A n e n q u i r y i n t o t h e p s y c h o l o g y of e t h i c s . ) M i n d , 1 9 3 9 , 4 8 , 3 9 - 5 7 .

5 . FRENKEL-BRUNSWIK,E.,LEVINSON,D.J.,and SANFORD,R.N.

The a n t i - d e m o c r a t i c P e r s o n a l i t y . I n T.M.Newcomb and

E . L . H a r t l e y ( e d s ) , R e a d i n g s i n s o c i a l p s y c h o l o g y .

New Y o r k : H o l t , 1 9 4 7 , P p . 5 3 1 - 5 4 1 .

6 . G U I L F O R D , J . P . , a n d DALLENBACH,K.M. A s t u d y of t h e a u t o k i n e t i c S e n s a t i o n . J . A m e r . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 2 8 , 4 0 , 8 3 - 9 1 .

7 . HEBB,D.O. The O r g a n i z a t i o n of b e h a v i o r . New Y o r k :

J o h n W i l e y & S o n s , 1 9 4 9 .

8 . HELS0N,H. A d a p t a t i o n - l e v e l a s a b a s i s f o r a q u a n t i t a t i v e t h e o r y of f r a m e s of r e f e r e n c e .

P s y c h o l . R e v . , 1 9 4 8 , 5 5 , 2 9 7 - 3 1 3 .

9 . HUNT,W.A. A n c h o r i n g e f f e c t s i n j u d g m e n t .

J . A m e r . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 4 1 , 5 4 , 3 9 5 - 4 0 3 .

1 0 . KOHLER,W. The p l a c e of v a l u e i n a w o r l d of f a c t .

New Y o r k : L i v e r i g h t , 1 9 3 8 .

1 1 . KRECH,D.,and CRUTCHFIELD,R.S. Theory and P r o b l e m s of s o c i a l p s y c h o l o g y . New Y o r k : M c G r a w - H i l l , 1 9 4 8 .

1 2 . LEWIN,K. E n v i r o n m e n t a l f o r c e s i n c h i l d b e h a v i o r and d e v e l o p m e n t . I n C . M u r c h i s o n ( e d ) , A handbook of c h i l d p s y c h o l o g y . C l a r k U n i v e r s i t y P r e s s : W o r c e s t e r , 1 9 3 1 , 1 0 1 .

1 3 . LUC HINS, A . S . On a g r e e m e n t w i t h a n o t h e r ' s j u d g m e n t .

J . a b n o r m . s o c . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 4 4 , 3 9 , 9 7 - 1 1 1 .

1 4 . LUCHINS,A.S. A c o n f l i c t i n n o r m s : m e t r i c v e r s u s E n g l i s h u n i t s o f l i n e a r m e a s u r e m e n t . J . s o c . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 4 7 , 2 5 , 1 9 3 - 2 0 6

1 5 McGARVEY,H.R. A n c h o r i n g e f f e c t s i n t h e a b s o l u t e j u d g m e n t of v e r b a l m a t e r i a l s . A r c h . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 4 2 - 4 3 , 3 9 , N o . 2 8 1 , 1 - 8 6 .

— 42 —

1 6 . MURPHY,G.,MURPHY,L.B.,and NEWCOMB,T.M. E x p e r i m e n t a l s o c i a l p s y c h o l o g y . New Y o r k : H a r p e r & B r o t h e r s , 1 9 3 7 .

1 7 . MURPHY,G. H i s t o r i c a l i n t r o d u c t i o n t o modern p s y c h o l o g y .

New York: H a r c o u r t , B r a c e & C o . , 1 9 4 9 .

1 8 . PRATT,C.C. Time e r r o r s i n the method of S i n g l e S t i m u l i .

J . e x p . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 3 3 , 1 6 , 7 9 8 - 8 1 4 .

1 9 . ROKEACH,M. G e n e r a l i z e d mental r i g i d i t y as a f a c t o r i n e t h n o c e n t r i c i s m . J . a b n o r m . s o c . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 4 8 , 4 3 , 2 5 9 - 2 7 8 .

2 0 . SCHONBAR,R.A. The i n t e r a c t i o n of o b s e r v e r - p a i r s i n j u d g i n g V i s u a l e x t e n t and movement:The f o r m a t i o n of s o c i a l norms i n " s t r u c t u r e d " s i t u a t i o n s . A r c h . P s y c h o l . ,

1 9 4 5 , N o . 2 9 9 .

2 1 . SHERIF,M. A s t u d y of some s o c i a l f a c t o r s i n p e r c e p t i o n .

Arch.Psych o l . , 1 9 3 5 , 2 7 , N o . 1 8 7 .

2 2 . SHERIF,M. The p s y c h o l o g y of s o c i a l norms. New York:

H a r p e r & B r o s . , 1 9 3 6 .

2 3 . SHERIF,M. An o u t l i n e of s o c i a l p s y c h o l o g y . New York:

Harper & B r o s . , 1 9 4 8 .

2 4 . SHERIF,M. Group i n f l u e n c e s upon the forma t i o n of norms and a t t i t u d e s . In T.M.Newcomb and E . L . H a r t l e y e t a l ,

Readings i n s o c i a l p s y c h o l o g y . New York : H o l t , 1 9 4 7 , 7 7 - 9 0 .

2 5 . STAGNER,R.,and OSGOOD,C.E. Impact of war on a n a t i o n a l i s t i c frame of r e f e r e n c e :1.Changes i n g e n e r a l a p p r o v a l and q u a l i t a t i v e p a t t e r n i n g of c e r t a i n s t e r e o t y p e s . J . s o c . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 4 6 , 2 4 , 1 9 7 - 2 1 5 .

2 6 . TRESSELT,M.E.,and VOLKMANN,J. The p r o d u c t i o n of u n i f o r m o p i n i o n by n o n - s o c i a l S t i m u l a t i o n .

J . a b n o r m . s o c . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 4 2 , 3 7 , 2 3 4 - 2 4 3 .

2 7 . V0TH,A.C. I n d i v i d u a l d i f f e r e n c e s i n the a u t o k i n e t i c phenomenon. J . e x p . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 4 1 , 2 9 , 3 0 6 - 3 2 2 .

2 8 . WERTHEIMER,M. Some problems i n t h e t h e o r y of e t h i c s .

S o c i a l R e s e a r c h , 1 9 3 5 , 2 , 3 5 1 - 3 6 7 .

2 9 . WEVER,E.G.,and ZENER,E. Method of a b s o l u t e judgment i n p s y c h o p h y s i c s . P s y c h o l . R e v . , 1 9 2 8 , 3 5 , N o . 6 , 4 7 5

3 0 . W00DR0W,H. W e i g h t - d i s c r i m i n a t i o n with a v a r y i n g

S t a n d a r d . J . A m e r . P s y c h o l . , 1 9 3 3 , 4 5 , 3 9 1 - 4 1 6 .

McGILL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY