Who Where the European Settlers

advertisement

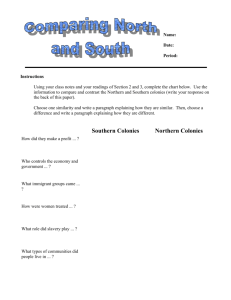

Who Were the European Settlers- where did they come from, why did they come, and what did they make? By Lauren Pacek, Research Analyst, Friends of Susan Combs February 10, 2015 Where Did They Come From? Country England (Virginia Company of London) England (Pilgrims) Timeline 1607 Where they settled Jamestown, Virginia (first permanent English settlement) Plymouth Bay Colony, Massachusetts Number 144 Why they left Europe To explore and settle 102 New Netherland which became New York Delaware Bay and along the Delaware River Massachusetts Bay Colony (Boston and Salem) 10,000 Left England to escape religious persecution. Originally went to Holland but couldn’t find good work so they went to the New World. Trade Holland 1620 Sweden 1630 600 Trade England (Puritans) 1630-1640 The Great Migration 20,000 1642 Virginia 30,000 1675 1682 1683 West Jersey and Delaware Bay, Pennsylvania Georgia, Pennsylvania 23,000 France 1685 100,000 Scotch-Irish Scotts Northern England 1750-1770 Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, South Carolina The frontier/ back country/ mountains Germany (Hessian Mercenaries) After the Rev. War Left England because the Church of England was trying to get rid of the Puritan influence in the church. English Civil War sent many English elite to the New World along with indentured servants The Quakers rejected social hierarchy. First went to Holland and then England to escape economic and political hardships Louis XIV revoked Edict of Nantes sending Huguenots to England and then to America A series of crop failures and resulting famine. Wars and other conflicts exiled many Scotts to America Mercenaries fought for the British were taken captive by the Americans and decided to stay in America instead of retiring to Germany after the war. England (Cavaliers & Servants) England (Quakers) Germany 1620 84,000 74,000 5,000 Why did they come? Western Europe was very poor in the 15th century. The estimated GDP was $450 at the beginning of the Christian Era and remained about the same until the 16th century (Kenny and Kenny 2006; Maddison 2001). The Ottomans and Venetians controlled access to the Mediterranean and the trade routes to Asia. Western Europe needed to find an alternate route to Asia (Schaller et al 2013, 16). Lauren Pacek Page 1 2/19/15 At the time, a nation’s wealth was measured by its gold and silver reserves. New trade routes and new lands meant new sources of gold and silver for the royal treasuries of Europe. Seventy years after Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean, Spain established the first North American colony at St. Augustine, Florida. (Schaller et al 2013, 32). During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, England was finally politically stable enough to send out their own expeditions to the New World (Schaller et al 2014, 53). Groups of English merchants were creating companies to fund trade expeditions to Eastern Europe, Asia and the Mediterranean (Schaller et al 2013, 53). In what would become the United States, the Virginia Companies of London and Plymouth were granted charters to establish settlements (Wolfe 2014b). New Netherland is now New York but began as a Dutch West India Company trading post to facilitate trade with local Native Americans, but it was not a priority for the Dutch Republic. People in the Dutch Republic enjoyed a prosperous economy and religious tolerance, so few citizens settled in the colony. However attractive land grants and the promise of religious tolerance attracted many Swedish and English settlers (Schaller et al 2013, 64, 70). Religious Freedom Religious freedom was an attractive concept in those years because there was so little tolerance in Europe. Uniformity of religion was a conviction held by people at the time, which meant everyone had to worship in the same way. It was believed that heretics not only damned themselves but the community as a whole (LOC). The group we now know as the Pilgrims were separatists from the Church of England. They believed that the church was not a true church and was beyond repair. Thinking like this was illegal and many Separatists were jailed for their beliefs. The Puritans also believed that the Church of England had strayed from the original teachings, but they were not as radical as the Pilgrims. The Puritans accepted that the Church of England was the true church but it needed some serious reforms. Still, the Puritans faced persecution from the church majority and civil authorities. They were told to conform or be “extripat[ed] from the earth” (LOC). One Puritan man was sentenced to life in prison, had his nose slit and had SS (for sower of sedition) branded on his forehead (LOC). The Salzburgers were another group of religious dissenters who found themselves seeking freedom from persecution. They were kicked out of their homeland in Salzburg, Austria. In total, 20,000 people fled Austria for London and then America. Economic Freedom The population in England nearly doubled in the years between 1500 and 1650, but the economy could not grow fast enough to keep up with population growth. Large landowners cut off access to small farmers leaving little land for grazing and farming. “To English men, land ownership brought respect, economic independence and political rights” (Schaller et al 2013, 61). Lauren Pacek Page 2 2/19/15 At around 1610, the Virginia Company allowed settlers to own land and the prospect of landownership brought tens of thousands of men to the New World, mostly as indentured servants. The Virginia Company encouraged this new influx of colonists by granting 50 acres to every free adult plus 50 acres for each servant (Schaller et al 2013, 60). In the 1760s people from Northern England, Ireland and Scotland fled their homelands due to increasing rents and crop failures. They settled in the western edges of the colonies (Schaller et al 2013). What did they find? A Terrible Journey The voyage across the Atlantic from England to the New World lasted about seven weeks and was very rough. One hundred or so passengers were packed into merchant ships that were little more than little wooden ships. The Mayflower transported 102 Pilgrims from Plymouth, England to Plymouth Harbor in 1620. The ship was estimated to be a mere 113 feet long (a Boeing 777-200LR, used for longdistance travel today, is 209 feet) with the passengers being relegated to a small portion of the ship. One German traveler, Gottleb Mittelberger wrote of his 1750 journey: During the voyage there is on board these ships terrible misery, stench, fumes, horror, vomiting, many kinds of seasickness, fever, dysentery, headache, heat, constipations, boils, scurvy, cancer, mouth rot, and the like, all of which come from old and sharply salty food and meat, also from very bad and foul water, so that many die miserably. Children from one to seven years rarely survive the voyage; and many a time parents are compelled to see their children miserably suffer and die from hunger, thirst, and sickness, and then cast them into the water.” A Harsh Climate The thinking of the time was based on a geography treatise written in the 2nd century AD that stated all lands on the same latitude would have the same climate. This thinking fails to take into account the many other factors that contribute a location’s weather. The Chesapeake is along the same latitude as well-known lands with temperate Mediterranean climates like Greece and Italy (Wolfe 2014a). This was also the time of the Little Ice Age. Early settlers landed in the American colonies to find the coldest winters in 1000 years and driest summers in 700 years (Wolfe 2014a). Poor crops led to increased conflicts over scarce resources between the native tribes and the European settlers (Wolfe 2014a). Massachusetts Bay Colonist, Roger Clap, wrote of his first year in his memoirs: Lauren Pacek Page 3 2/19/15 In our beginning many were in great straits for want of provision for themselves and their little ones. Oh the hunger that many suffered, and saw no hope in an eye of reason to be supplied, only by clams and mussels and fish. We did quickly build boats, and some went a fishing. But bread was with many a very scarce thing, and flesh of all kind as scarce (National Humanities Center 2006). An American Economy The American colonies were a blank canvas to paint their shared vision of the perfect life. For the first 50 years, the English crown and Parliament had very little influence over the American colonies (Cohen 2004). The end of the English Civil War and the Restoration of Charles II (1642-1660) brought about more and more restrictions on commerce and trade for the colonies. The belief that the purpose of a colony was solely to benefit the homeland was held by England at the time. American colonists worked harder and diversified their labor. American manufacturing increased dramatically in the late 1600s and early 1700s. By 1715 the colonies had become self-sustaining (Cohen 2004) and by 1730 they had laid the “foundations for the economic development that would become the United States by intensifying old activities and developing new ones in response to overseas and domestic markets” (Schaller 2013, 159). Due to the enterprise and commerce of the colonists, the American colonies enjoyed one of the highest standards of living for the time (Cohen 2004). A Literate Citizenry The Massachusetts Bay Colony made a law requiring a public grammar school in every town with more than 100 households (Schaller et al 2013, 73). New Englanders were quick to found a university, Harvard, in 1636. Yale was founded in 1701. The University of Pennsylvania, Columbia, Princeton, Rutgers and Brown were all founded between 1746 and 1766. It was considered essential that the colonist be able to read. An estimated 80% of New England adult males were literate compared to 60% back in England (Ferguson 1997, 432) The Boston News-letter, the first successful American newspaper, was founded in 1704 (Schaller 2013, 163) followed by many more in every city. In 1734 one newspaper printer was acquitted of libel against the governor of New York, “the verdict set a precedent that people had the right to monitor leaders’ actions and challenge them in print in order to preserve liberty” (Schaller 2013, 191). Link to The Boston News-letter: http://www.earlyamerica.com/earlyamerica/firsts/newspaper/ The Age of Enlightenment The 17th and 18th centuries saw a new way of thinking about man and his environment. The Age of Enlightenment began with a scientific revolution that favored reason over tradition. These thoughts were being promoted in the large number of newspapers and coffee houses in the American colonies. Immanuel Kant, a German Enlightenment philosopher answered the question of “What is Enlightenment” with it is “man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity”. “The Enlightenment in Lauren Pacek Page 4 2/19/15 America is sometimes conveyed in a single phrase, the political right of self-determination realized” (Ferguson 1994, 368). Again, Kant explained this as overcoming “the inability to use one’s own understanding without the guidance of another” (Kant 1784). David Ramsay, in 1789, wrote “The History of the American Revolution”. In it he said, “in establishing American independence the pen and the press had equal merit to that of the sword” (Ferguson 1994, 426). John Adams believed that Europe, at the time, was ruled by confederation of the clergy and the feudal system, while Americans established the colonies “in direct opposition to the canon and feudal systems”. He argued that European princes and clergymen used the ignorance of the people to keep them subservient (Ferguson 1994, 435), thus “care has been taken that the art of printing should be encouraged and that it should be easy and cheap and safe for any person to communicate his throught to the public” (Adams, 1765). It was at about this time, newspapers started referring to the colonists as Americans instead of Englishmen (Ferguson 1994, 436). The pamphlet was the perfect medium to circulate the radical thoughts. The most famous one of the time was Common Sense, written by Thomas Paine, originally published anonymously in early 1776. The pamphlet became a rallying cry for independence with what Paine said was, “nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments and common sense” (Paine 1776). Link to Common Sense’s original title page: http://www.earlyamerica.com/wpcontent/uploads/2015/01/CommonSenseTitlePage.jpg What Did They Make? The Declaration of Independence As Great Britain tried to take more control over the colonies Parliament passed more and more regulations restricting commerce and taxing the colonists to pay for Great Britain’s debts. It finally got to be too much. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people. Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here” (Declaration of Independence). The American Declaration of Independence was not the first declaration the world had seen. It was not addressed to the King, Parliament or Great Britain, but to world. It was a declaration of independence and a declaration of war. Lauren Pacek Page 5 2/19/15 The Declaration uses phrases that can be found in many Enlightenment era writings but the meat of the text draws upon the public documents of the colonies themselves- state constitutions, compacts, and resolutions. The document is a combination of the shared grievances of the thirteen colonies against the tyranny of a too powerful central government. References Constitution. 2014. In Dictionary of British history, ed. John Canon. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Immigration in U.S. history. 2006. Ed. Carl L. Bankston and Danielle Antoinette Hidalgo. Vol. 1. Pasadena, C.A., Salem Press. America as a religious refuge: The seventeenth century, part 1 - religion and the founding of the American republic. Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel01.html (accessed 1/27/2015). American colonial life. How Stuff Works- The Discovery Network. http://history.howstuffworks.com/american-history/american-colonial-life.htm (accessed 1/27/2015). Achenbach, Joel. 2003. Publish or perish: The untold story of Thomas Harriot, the greatest scientist you've never heard of. National Geographic Magazine. Bristow, William. 2010. Enlightenment. In Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. Stanford, CA: Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. Cohen, Charles L. 2004. Colonial era. In The Oxford companion to united states history, ed. Paul S. Boyer. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. Ferguson, Robert A. 1994. The American enlightenment, 1750-1820. In Cambridge history of American literature, ed. Scvan Bercovitch. Vol. 1, 347. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. Gormley, Myra. 2000. Migration patterns of our Scottish ancestors American Genealogy Magazine. http://www.genealogymagazine.com/scots.html (accessed 1/27/2015). Kenny, Anthony and Charles and Kenny. 2006. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of utility. St. Andrews studies in philosophy and public affairs. Exeter, U.K.: Imprint Academic. Mittelberger, Gottlieb. 1898. Gottlieb Mittelberger's journey to Pennsylvania in the year 1750 and return to germany in the year 1754. Trans. Carlo Theo Eben. Philadelphia, PA: John Jos. McVey. Pocock, J. G. A. 2003. The Machiavellian moment : Florentine political thought and the Atlantic republican tradition. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Lauren Pacek Page 6 2/19/15 Schaller, Michael. 2013. American horizons: U.S. history in a global context. Concise Edition ed. Vol. 1. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. Smith, Adam and Tom Butler-Bowden. 2010. The wealth of nations. The Economics Classic- A Selected Edition for the Contemporary Reader ed. Oxford, UK: Capstone Publishing Ltd. Wolfe, Brenden. 2013. Little ice age and colonial Virginia. Chap. 1/27/2015, In Encyclopedia Virginia. Charlottesville, Virginia: Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Little_Ice_Age_and_Colonial_Virginia_The. ———. 2013. Virginia Company of London. In Encyclopedia Virginia. Charlottesville, VA: Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. http://encyclopediavirginia.org/Virginia_Company_of_London . Lauren Pacek Page 7 2/19/15