Slavery and Politics to 1808 - University of North Carolina Press

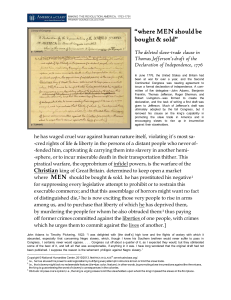

advertisement