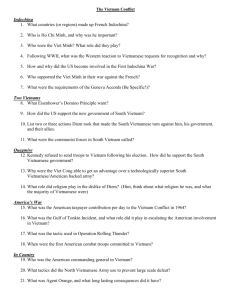

Myths of the Vietnam War

advertisement