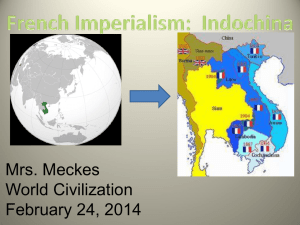

Vietnam vs. Indochina: Space in Vietnamese Nationalism (1887-1954)

advertisement