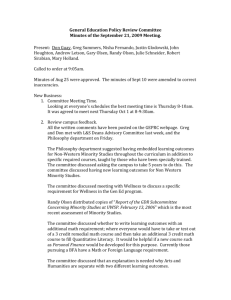

View PDF - Minnesota Law Review

advertisement