constitution 6ed - University of Georgia Libraries

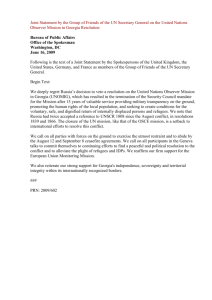

advertisement