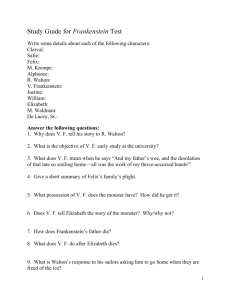

Frankenstein Table of Contents Chapter 1-10 Summary

advertisement