NEW ARTIFACTS - OCAD University Open Research Repository

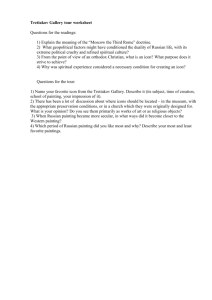

advertisement