Understand Ylds 12-03 c

advertisement

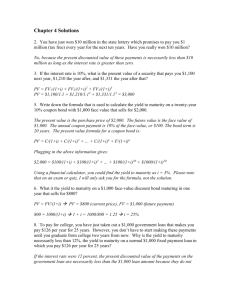

Understanding Yields When dealing with bond mutual funds, one of the more confusing topics tends to revolve around fund yields. There seems to be a never-ending array of yields, including yield-to-maturity, distribution yield, indicated yield, 12-month yield, 7-day yield, and the list goes on. Interpreting yields adds to the confusion. For instance, the term “yield” is often mistakenly translated to mean “income rate,” which is only correct in some instances. Hopefully, this write-up will help clarify the definitions and interpretations of the most commonly utilized “yields” that are reported in conjunction with the Dryden fixed income mutual funds. CURRENT YIELD AND DISTRIBUTION YIELD By its simplest definition, “yield” is the return an investor receives on a bond (or bond fund) based on the price paid and the coupon interest received. Yields can be broken down into two basic classifications, current yield and yield-to-maturity. Current yield is the easiest type of yield to compute, and is often the yield most investors (sometimes mistakenly) focus on in evaluating the attractiveness of a specific bond or bond fund. Current yield relates the annual coupon interest received from a bond to its market price, thus providing a reasonable estimate of the income generated from the security at a specific point in time. It considers only coupon interest, and does not account for capital gains or losses that could be realized by the investor, nor the effects of compounding as a result of reinvested interest. The formula for calculating current yield is as follows: Current Yield = Annual dollar coupon interest/Price When applied to bond funds the formula varies slightly to account for the fact bond fund dividends are generally not fixed.* Distribution yield is reported for the Dryden bond funds to provide our investors with an estimate of the income paid out by the fund. Distribution yield is calculated by adding the trailing 12-months per share dividend and dividing the sum by the Fund’s month-end NAV. Morningstar and Lipper both provide a “12 Month Yield” to reflect distribution yield using a very similar calculation. The key difference between distribution yield and current yield is that the distribution yield, by including the past 12-months dividend payments, is backward looking and should not be used to illustrate a fund’s expected income going forward. As we know, in a falling rate environment, bond prices rise. Since a bond’s price is a key determinant of the distribution yield, falling interest rates will impose downward pressure on the distribution yield. Additionally, because funds are actively traded, in a falling rate environment, lower coupon bonds and/or high coupon bonds priced at increasing premiums will be added to the portfolio, adding further downward pressure on the distribution yield. Since the reported distribution yield includes monthly dividend payments up to 12 months old, the reported yield can overestimate the distribution rate that would more likely be realized by the investor at that point in time. Of course, the reverse would transpire during a rising rate environment. A more timely indicator of a fund’s current distribution rate is the 30-Day Yield (not to be confused with the 30Day SEC Yield discussed later), which is an annualized yield based on the income paid out by the fund over just the past 30 days, not the preceding 12 months. Bloomberg provides a similar yield called Indicated Yield. To calculate a 30-Day Yield or Indicated Yield, simply annualize the past 30-days’ distributions, and divide the product by the current fund price. * Most bond funds pay floating rate dividends as opposed to fixed rate dividends. While an attractive feature to some investors, fixed rate dividends can force a fund’s manager to focus on achieving the required yield, which can disrupt the fund’s appropriate risk/return profile. All Dryden bond funds are managed with an emphasis on total return, not distribution yield, and pay fluctuating dividends. IFS-A086708 Calculating Current Yield and Distribution Yield While the bond’s coupon is fixed, its current yield varies with the price of the bond or bond fund. Years to maturity is not a factor in calculating current yield. Example 1: Corporate Bond Scenario 1 Purchase price = $1000 (par) Annual Coupon = $80 (8%) Current Yield = $80/$1000 = 8% ABC Corporation, 8.00%; 06/15/2013 Scenario 2 Purchase price = $900 Annual Coupon = $80 (8%) Current Yield = $80/$900 = 8.89% Example 2: XYZ Bond Fund NAV Monthly Per Share Dividends = $11.50 Distribution Yield = $0.545391 (12 month dividend total) $11.50 (NAV) = 4.74% 30-Day, or Indicated Yield (as of 9/30/03) = 0.047012 x 12 = 4.91% 11.50 31-Oct-02 0.046459 30-Nov-02 0.047001 31-Dec-02 0.059619 31-Jan-03 0.032176 28-Feb-03 0.049420 31-Mar-03 0.041239 30-Apr-03 0.045072 31-May-03 0.043782 30-Jun-03 0.044390 31-Jul-03 0.045214 31-Aug-03 0.044007 30-Sep-03 0.047012 12 Month 0.545391 YIELD-TO-MATURITY AND 30-DAY SEC YIELD As noted above, the current yield and distribution yield provide rough estimates of the expected income rate of a bond or bond fund at a point in time. However, these yields do not take into account the potential impact of changes in interest rates. A more comprehensive yield calculation that does take this into account is Yield-toMaturity, or as it applies to mutual fund products, the 30-Day SEC Yield. Yield-to-Maturity (YTM) reflects the internal annual rate of return an investor would realize by purchasing a bond, holding it to maturity and reinvesting all coupon interest received at the same YTM. Another way to think about YTM is as the interest rate that will make the present value of the bond’s cash flows equal to its purchase price. Unlike the current yield, YTM does incorporate the capital gain/loss the investor would experience on the purchase price, as well as the contribution of reinvested dividends. Therefore, if a bond is purchased at a premium (i.e. market yields are lower than the bond’s coupon rate), its yield-to-maturity will be less than its coupon rate because the investor would realize a capital loss on the bond when it matures at face value (par) and would be reinvesting coupons at lower rates over time. Conversely, if the bond is purchased at a discount (i.e. market yields are higher than the bond’s coupon rate), its yield-to-maturity will be higher than its coupon rate. Additionally, it is forward looking, as opposed to the current yield that looks backward, and is considered a more accurate indication of the return the investor will experience. It also allows you to compare bonds with different maturities and coupons. Please see the call out box on the next page for an illustration on determining yield-to-maturity. Yield to Maturity Yield-to-Maturity is the interest rate that will make a bond’s price equal to the sum of its cash flows. It is generally calculated using a financial calculator – it is not solvable through simple arithmetic. Consider the example of a 5-Year, 6% Coupon Bond: Current Coupon Bond (market rate = coupon rate) Premium Bond (market rate < coupon rate) Discount Bond (market rate > coupon rate) Bond Price = $100.00 Yield to Maturity = 6% Bond Price = $104.33 Yield to Maturity = 5% Bond Price = $95.90 Yield to Maturity = 7% Period Cash Flows Present Value* (@ 6%) Present Value* (@ 5%) Present Value* (@7%) 1 $6.00 $5.66 $5.71 $5.61 2 $6.00 $5.34 $5.44 $5.24 3 $6.00 $5.04 $5.18 $4.90 4 $6.00 $4.75 $4.94 $4.58 5 $106.00 $79.21 $83.05 $75.58 Bond Price = $100.00 $104.33 $95.90 * Present Value = Future Value [1/(1+i)N], where i = interest rate, and N = number of periods. Yield-to-call is calculated the same way, however it assumes that a callable bond that is purchased at a premium will be called (i.e. the investor will receive face value) on the bond’s call date. Sometimes the term “yieldto-worst” is used to ensure that the investor is looking at the most conservative scenario in evaluating a bond. The “yield-to-worst” is the lower of the yield-to-call and yield-to-maturity. The 30-Day SEC Yield is similar to the yield-to-maturity and is reported for mutual funds. It was introduced by the SEC as a means of standardizing reported yields across all funds to foster a fair, “apples-to-apples” comparison and eliminate misleading performance and income claims. While the formula for computing the 30Day SEC Yield is quite complex and beyond the scope of this writing, the statistic is similar to yield-to-maturity, and includes fund fees and expenses.* * The formula for 30-Day SEC Yield is as follows: Yield = 2 [( a-b +1 cd ) ] 6 -1 a = Dividend and interest income b = Expenses accrued for the period (net of expense reimbursement) c = Average daily number of shares outstanding during the period that was entitled to receive dividends d = Maximum offering price per share on the last day of the period Interpreting Yields Case Study: Dryden Total Return Bond Fund As of September 30, 2003, the Dryden Total Return Bond Fund’s (A shares) distribution yield (at NAV) and 30-Day SEC Yield are 4.52% and 2.83%, respectively. Why are these yields so different? The answer lies in the composition of the Fund’s holdings. Since the distribution yield exceeds the 30-Day SEC Yield, the likely explanation is that the fund holds high coupon bonds priced at a premium. This is in fact the case with the Dryden Total Return Bond Fund, as reflected by the fund’s average price of 102.968 (par = 100). The portfolio’s holdings have increased in value as market rates have fallen, while premium prices have been paid to acquire new securities whose coupon rates exceed those available in the current market. As a result, the fund’s distribution yield (which only considers income paid) is high relative to its 30-Day SEC Yield (which is based on yield-to-maturity). In general, after a prolonged period of falling interest rates, as we’ve experienced from 2000 through 2003, many funds will likely show distribution yields that are higher than their 30-Day SEC yields. This is logical, since bond prices rise as interest rates fall. Their coupon rates, however, have remained constant while the bonds’ prices have risen as interest rates have trended down. The reverse can be expected following a rising rate cycle. As of September 30, 2003, the Dryden Total Return Bond Fund’s A share average annual total returns were as follows: 1-year: 3.50%,5-year: 4.51%, since inception (1/10/1995) 6.90%. The Fund may invest up to 50% in high yield, or “junk” bonds, which are subject to greater credit or market risks. The Fund may invest up to 45% in foreign securities, which are subject to the risks of currency fluctuation and the impact of social, political and economic change. Mortgage-backed securities are subject to prepayment and extension risks. These risks may result in greater share price volatility. Past performance does not guarantee future results and current performance may be lower or higher than the performance data quoted. The investment return and principal value will fluctuate and shares when sold may be worth more or less than the original cost. For more information about the Dryden Total Return Bond Fund and for a free prospectus, call your financial professional. You should consider the fund's investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses carefully before investing. The prospectus will contain this and other information about the investment company. Please read the prospectus carefully before investing. Shares of the fund are distributed by Prudential Investment Management Services LLC (PIMS). PIMS is a Prudential Financial company and member SIPC. JennisonDryden is a service mark of The Prudential Insurance Company of America. SUMMARY S o, what should investors focus on, Distribution Yield or 30-Day SEC Yield? This will depend on the investor’s objective and time horizon. Investors with a very short term time horizon (less than a few months) may find the distribution yield to be useful, since they might only focus on the dividend payments for a few months and may be willing to assume that the markets will not fluctuate significantly during this time. Similarly, income-oriented investors who receive cash distributions and depend on a consistent monthly payment may find it meaningful since it reflects only the distributions they can expect to receive. But remember, most funds’ dividend rates are not fixed, so the distribution yield should be used only as a guideline to approximate the expected cash flows for the next month or two. Further, and more importantly, dividend distributions tell only part of the story for bond fund returns. Any investor who is planning to hold a bond fund over time should look at both dividends and capital gains and losses. As such, the 30-Day SEC Yield is a more accurate estimator of the return an investor will experience with his or her bond fund investment over a longer period of time. Remember, total return matters with bond fund investments. Many dynamic factors such as interest rates and credit fundamentals affect the value of a bond or bond fund, and the 30-Day SEC Yield incorporates these factors into its calculation. Additionally, because of its standardized formula, the 30-Day SEC Yield can be used to compare funds when making investment choices. We suggest that all investors, including those with income objectives, consider the 30-Day SEC Yield when selecting bond mutual funds, while using the distribution yield to estimate the current monthly distributions only where applicable for certain investors. The comments, opinions and estimates contained herein are based on or derived from publicly available information from sources that Prudential Fixed Income believes to be reliable. This outlook, which is for informational purposes only, sets forth our views as of this date. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change.