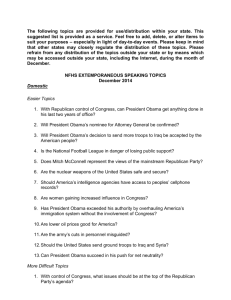

The Obama Administration's Unprecedented

advertisement