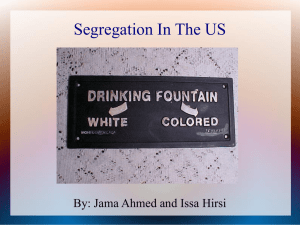

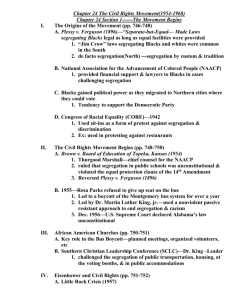

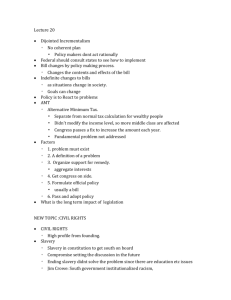

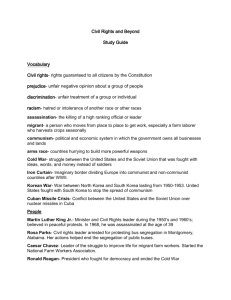

Segregation and Black Political Efficacy

advertisement