Fall 2007

advertisement

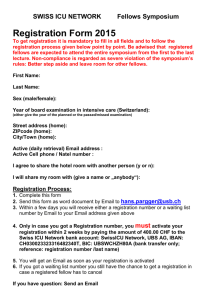

Volume 18 • Number 2 • FALL 2007 Message From The President Judy Miller Associate Dean for Special Academic Initiatives, Clark University I begin my term as President of NEFDC at an exciting time for the organization! Under the leadership of recent past Presidents Judith Kamber, Tom Edwards, and Jeff Halprin, the organization has grown steadily. Our fall and spring conferences have attracted increasing numbers of enthusiastic attendees from an expanding geographic area, drawn in part by our ability to book high-quality and high-profile keynote speakers. Our experimental collaborations with other organizations and interest groups for our two most recent spring conferences have been astoundingly successful. The increasing size of our conferences has necessitated a series of changes in conference venue, most recently a move of the fall conference to the DCU Center in Worcester, Massachusetts. Our newsletter continues to grow, in volume and in quality, under the recent guidance of our dedicated editors Jeff Halprin, Tom Thibodeau, and Steve Berrien. In spite of, or perhaps because of, all of this growth, our organization remains on sound financial footing under the watchful eye of our conscientious treasurer Charlie Kaminski. Clearly the word is spreading that NEFDC offers accessible, affordable, and high-quality opportunities to connect with the region’s most engaged and active faculty for the improvement of teaching and learning. Our next opportunity for such connections, and our flagship event of the year, is our upcoming fall conference on Friday, Nov. 9. Our keynote speaker is George Kuh, the director of the Center for Postsecondary Research at Indiana University that originates and administers NSSE, the National Survey of Student Engagement. If you haven’t yet registered, take a moment right now to do so—there is a registration form conveniently located inside this newsletter! Our conference theme, engaged learning, prompted an unprecedented number of proposal submissions, and the contributed sessions show every indication of exceeding previous high standards. The theme of engaged learning invites and challenges us to engage with each other as we take a mini-retreat from our responsibilities, just for one day, and contemplate how best to foster the success of our students, both in and out of the classroom. The work of the organization is done almost entirely by the highly engaged volunteer members of the Board of Directors. Most Board members serve in multiple roles, as officers, editors, and conference organizers, sometimes filling more than one role at the same time. Our single retiring Board member, Judith Kamber (Northern Essex Community College), is no Continued on page 3 From the Editors: The theme of the upcoming NEFDC Spring Conference is: “Engaging Learning: Fostering Student Success.” Accordingly, two of the articles in this issue of the NEFDC Exchange address that theme. The first article is an abstract from George Kuh that outlines the direction of his keynote address. The second article describes activities that engage students through service learning projects. The final two articles discuss two different methods of faculty development: reciprocal mentoring at UMASS Amherst and the development and use of interactive TV at UCONN. Other parts of the newsletter provide information about resources and activities that promote professional development. And of course the events, the newsletter, and the website sponsored by NEFDC, as described throughout this issue, all exist purely to support professional development for faculty and staff. We hope you enjoy this issue, and we welcome your feedback and future contributions. If you would like to submit an article for our Spring newsletter please email a word document to tthibodeau@neit.edu by March 1, 2008. In This Issue... NEFDC Fall 2007 Conference. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 Helpful Suggestions for Teaching Interactive Television Courses. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 Engaged Learning: The Foundation for Student Success . . . . . . . 2 Meet Our New Board Members. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 Fall Conference Agenda. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 Connecting With Others. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 Learning Through Community Engagement. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 www.NEFDC.org . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 Reciprocal Mentoring . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 NEFDC Fall Conference Registration Form . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15 NEFDC FALL 2007 CONFERENCE “Engaged Learning: Fostering Student Success” Featuring Dr. George Kuh, Indiana University Friday, November 9, 2007 DCU Center Worcester, Massachusetts George D. Kuh is Chancellor’s Professor of Higher Education at Indiana University Bloomington where he directs the Center for Postsecondary Research, home to the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) and related initiatives. A past president of the Association for the Study of Higher Education (ASHE), Kuh has written extensively about student engagement, assessment, institutional improvement, and college and university cultures and has consulted with more than 185 educational institutions and agencies in the US and abroad. His scholarly contributions have been recognized with awards from the American College Personnel Association, Association for Institutional Research, ASHE, Council of Independent Colleges, National Association of Student Personnel Administrators, and the National Center on Public Policy in Higher Education and Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. He holds honorary degrees from Millikin University, Washington and Jefferson College, and Luther College, where he is a member of the Board of Regents. In 2001, he received Indiana University’s prestigious Tracy Sonneborn Award for a distinguished career of teaching and research. Engaged Learning: The Foundation for Student Success A Note from our Fall Conference Keynote Speaker George Kuh Indiana University Javier is the first in his family to go to university. His residence hall houses 600 other first-year students but no one on his floor is in any of his classes, so he is pretty much on his own when it comes to studying. Unsure of her major, Sarah struggles with her writing, which was a problem in high school. After three semesters of university, only her composition course required a few short papers and all her tests so far were multiple choice or truefalse. A looming concern is that two of her finals this term will be essay exams. Nicole left university after her first year to get married. Now divorced with a child, she works 30 hours a week and is taking two classes this term. Her university experience is pretty much limited to finding a place to park near campus and going to class. Tens of thousands of undergraduates are like Javier, Sarah, and Nicole. They must deal with one or more circumstances that seriously challenge their ability to succeed in university. Socioeconomic background, financial means, family encouragement and support, and – most important -- taking the right kinds of courses in high school substantially influence whether a person will earn a credential or degree. Because the trajectory for academic success is established long before students matriculate, many universities have less-than-stellar graduation rates. Yet once students start, how much they get out of their studies and whether they persist are—to an appreciable degree— a function of how much time and effort they devote to productive activities. Toward these ends, some institutions have fashioned policies and practices that boost the performance of all students. 2 NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 My presentation will focus on the factors and conditions that promise to engage students like Javier, Sarah and Nicole at high levels in effective educational practices. I will describe promising, “high impact” practices, drawing on data from the National Survey of Student Engagement and the Faculty Survey of Student Engagement, my studies of strong performing universities, and my distillation of the research on student success conducted for the U.S. Department of Education. The focus will be on what faculty members can do to engage students in productive learning activities. For example, many students—especially those who commute—spend a limited amount of time each week on campus. The classroom is the only regular point of contact they have with other students and with faculty and staff members. This means that faculty members must be more intentional about teaching institutional values and traditions and informing students about campus events, procedures, and deadlines such as registration. Faculty members also can use cooperative learning activities to bring students together to work together after class on meaningful tasks. This is especially important because peers are very influential to student learning and values development. This is why high quality first-year seminars and learning communities (where students take two or more courses together) can be so powerful. Finally, I will challenge participants to work collaboratively with the colleagues throughout the university to muster the will to more consistently use these promising policies and practices to increase the odds that more students get ready, get in, and get through. Message From The President Continued from page 1 exception. Since Judith and I superficially resemble each other, and since we share a name, I have joked with her that maybe no one will notice that the presidency has changed hands—but her passion and style are inimitable, and we will miss her greatly! As we go to press, we have received word of the resignation of long-time Board member Steve Berrien. Steve has been a mainstay of many conference and newsletter teams, and his will be big shoes to fill. We welcome our new Board members, Mei-Yau Shih (University of Massachusetts Amherst), Michelle Barthelemy (Greenfield Community College), and Donna Qualters (Suffolk University) and we offer our congratulations to our re-elected Board members, Tom Edwards (Thomas College), Keith Barker (University of Connecticut Storrs), Jeff Halprin (Nichols College), and Tom Thibodeau (New England Institute of Technology). We thank them all, and also our continuing Board members, for their willingness to contribute “sweat equity” to this terrific organization. (I hasten to point out that Board members feel amply rewarded by the opportunity to work closely with such a diverse, dedicated, and thoughtful group of colleagues.) The titles and contact information of all the Board members are in this newsletter and on the NEFDC web site (www.nefdc.org), and we all welcome your comments, questions, and suggestions. Classroom teaching can be an individual, even an isolated endeavor. But I think that, as educators, engagement—with students, with colleagues, and with issues in teaching and learning—is at the core of our professional responsibility. To me, this organization is fundamentally about engagement. It is a privilege for me to play a role in carrying on NEFDC’s tradition of engagement. Fall Conference Agenda Friday, November 9, 2007 DCU Center Worcester, Massachusetts 8:30 - 9:00 Conference Registration 9:00 - 9:15 Welcome, Introductions 9:15 - 10:30 Keynote Presentation George Kuh, Ph.D. Chancellor’s Professor of Higher Education Director, Center of Postsecondary Research Indiana University 10:45 - 11:45 Session I: Concurrent Workshops & Teaching Tips 12:00 - 1:00 Lunch 1:15 - 2:15 Session II: Concurrent Workshops & Teaching Tips 2:30 - 3:30 Session III: Concurrent Workshops & Teaching Tips Concurrent Workshops are interactive, 60-minute sessions that encourage participant involvement through case studies, discussion groups, role-playing, etc. Teaching Tips sessions are shorter, 25-minute topical presentations (2 per session). Poster Sessions allow presenters to highlight a particular program or initiative throughout the day. The NEFDC EXCHANGE Tom Thibodeau, New England Institue of Technology, Warwick, RI, Editor Jeanne Albert, Castleton State College, Castleton, VT, Editor The NEFDC EXCHANGE is published in the Fall and Spring of each academic year. Designed to inform the membership of the activities of the organization and the ideas of members, it depends upon member submissions. Submissions may be sent to either editor at tthibodeau@neit.edu or jeanne.albert@castleton.edu. Materials in the newsletter are copyrighted by NEFDC, except as noted, and may be copied by members only for their use. NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 3 Learning Through Community Engagement Kevin R. Kearney Associate Professor of Biochemistry and Director of Service-Learning Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Worcester, MA In this article, I will describe a Service-Learning (SL) course that I have taught for seven years and some of the educational outcomes of this course. Though the reference point of the present article will be this course, I will highlight course components and educational outcomes that should be broadly applicable. For those unfamiliar with SL, this will provide some ideas about how to incorporate this pedagogy in courses they teach. For current SL practitioners, it will provide some ideas about potential learning outcomes of SL and how to assess them. For the purposes of this article, I will define ServiceLearning as a learner-centered pedagogy, as part of which students (a) engage in service in the community and (b) learn by reflecting on it. The process must be reciprocal: the students must benefit by learning from the service, and those served must benefit from needed services. Service-Learning Course I will present the course I teach by describing (1) some general information about the course and the students, (2) the learning goals of the course, (3) assessment methods, and (4) teaching and learning activities. (1) General Information This course is a required 1-credit course for first-year pharmacy students. Approximately 2/3 of the students in this program have at least a bachelor’s degree, and the average age of the entering students is usually 27-28 years. Students in the course are required to attend a 1-hour weekly seminar, The assessment of learning is multifaceted, and associated with various service-site or classroom activities. 4 NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 and to do 2 hours of community service for 10 weeks. The class-size is usually 35-40 at our Worcester campus, and 20-25 at our Manchester, NH, campus. (2) Learning Goals Our college’s articulated goal is to educate communityoriented healthcare professionals (particularly pharmacists) for the 21st century. Following from this, it is clear that courses such as pharmacology must be part of our curriculum. However, pharmacists must also understand the complexities of their patients’ lives and the communities in which they provide pharmaceutical care. This is why we have the servicelearning course in our curriculum. The objectives of this course include both service and learning. There is one broadly stated service objective: The students must provide 20 hours of service over a 10-week period, and the service must meet the established needs of the people and organizations served. The learning objectives for the course were selected from objectives articulated by the Accreditation Council for Pharmaceutical Education. These include the following: • Develop or enhance communication skills. • Become familiar with the most critical needs of those served, with a special focus on culturally diverse and underserved populations. • Become familiar with the resources in the community (individuals, organizations, etc.) that are available to meet the needs of various populations, especially the underserved. • Develop critical-thinking skills. (3) Assessment The assessment of service is straightforward. Near the end of the semester, we send a brief evaluation form to each student’s supervisor at the service site, asking if the student visited the site regularly, and provided at least 2 hours of service work per week for at least 10 weeks. The supervisor is asked to answer affirmatively or negatively, and to comment on any problems, or to commend outstanding service. The assessment of learning is multifaceted, and associated with various service-site or classroom activities. In the evaluation form sent to on-site supervisors, they are asked, “From your observations, did this student learn through providing service?” They are also asked to evaluate the students’ oral communication skills (Excellent, Above-average, Good, Fair, Needs improvement). Though not very detailed, we consider this a good general indicator of skills. To assess the students’ skills communicating with groups, all are required to give a presentation during the last weeks of the course to the entire class about their service and learning accomplishments, and their fellow students and the instructor complete a brief evaluation of their presentations, assessing both content and delivery. The assessment of the students’ familiarity with the lifeissues of those they served is done by evaluating their weekly entries in a journal, the content of their oral presentations (lessons learned) and their responses to a written survey on the last day of class. (Queries: Describe what you learned from the most educational part of this course. Write about something you learned from your classmates’ presentations in the second half of the semester.) The assessment of the students’ knowledge about resources in the community is based on their journal entries, the information they provided in their oral presentations and a query in the written survey at the end of the course: Describe the services provided by two organizations where your classmates did SL work. Finally, the assessment of the students’ critical-thinking skills is based on the quality of their journal entries (beyond simple reporting of events, to analyses of the situations they encountered and the broader social issues they highlight) and the depth of their oral presentations. (4) Teaching/Learning Activities Students must provide 20 hours of service over a 10-week period. We have approximately 30 community organizations in Worcester, and 8 in Manchester, where the students can do their community-based work. We have selected these based on their needs, our students’ abilities and our learning goals (developing communication skills, learning about diverse populations, etc.). They include public schools, largely those educating underserved populations, where our students serve as tutors and mentors; organizations providing recreational and educational opportunities to children and youths outside the classroom; nursing homes and agencies serving seniors; homeless shelters; free medical clinics and an agency serving those with AIDS and their families and friends; organizations serving people with disabilities; and an agency serving adult speakers of languages other than English. At the beginning of the semester, each student and an on-site supervisor complete and sign a Service-Learning Agreement, enumerating their planned service activities and goals. Students must participate in a one-hour weekly seminar. Among the topics discussed in the seminar are: reflection on service as a tool for significant learning; assessing the quality of service; communication skills; cultural diversity and competency; and ethics in a diverse society. During the last four weeks of the semester, students give their oral presentations about their service work and associated learning. For this course, students purchase a journal that includes written guidelines for making entries, and spaces for weekly entries. In their entries, students are instructed to report their observations, activities, subjective reactions to their experiences, lessons learned from reflection on their work and societal issues that they encounter, and a weekly plan for action the following week based on their experiences to date. Educational Outcomes So what are the educational outcomes of this course? This has been the central question behind research I have carried out over several years. In a 2004 publication, I described students’ self-evaluations of their learning. (Kearney KR, Amer. J. Pharm. Ed. 68, Article 29, 1-13) Though such research points to possible learning, it is subjective. In an attempt to move toward more objective assessment, more recently I have asked students, in the survey on the last day of class (mentioned above), to describe what they have learned from the course. The area of learning that was most frequently mentioned by students was communication (41% of the respondents). This was reassuring, as it was one of the key educational objectives of the course. Several respondents pointed to the importance of listening skills, which had been a topic of discussion and practice during one of the seminars. Many reported improving their communication skills, referring to both one-on-one communication and giving presentations to a group. While no objective measurement of communication skills was done at the beginning or conclusion of the course, it is clear that the students were very aware of their importance, knew some of the elements of effective communication (e.g., active listening, speaking at a level appropriate to the listener), and were consciously working to improve their skills. The evaluation forms completed by the students’ site supervisors provide some information about the students’ oral communication skills. The supervisors rated 76% of the students’ skills as Excellent or Above-Average, and 19% as Good. Five percent of the students were rated as “Fair” or “Needs Improvement;” in all cases the supervisor indicated poor attendance or poor attitude as a reason for the low rating. Especially considering the fact that approximately 30% of the students speak a language other than English as their first language, these results suggest that the students are reasonably proficient in oral English. Though this does not necessarily mean that the students’ communication skills improved as a result of the course, they positively complement the students’ self-evaluations. Within the area of communication, a number of students specifically mentioned learning from experience about the importance and methods of explaining complex material in ways that are effective for relatively unskilled learners. One student reported learning “how to break down large topics into lay people’s terms.” Another student, who had tutored elementary school students, wrote that he had learned how “to get [the students] to understand subjects and ideas that [he had] mastered but [that the children had] minimal experience with.” The awareness and skills these students developed will be critically important when they are later working as pharmacists. Many respondents reported increased awareness of the ‘real-world’ needs of people in the community (12%), or of the wide variety of organizations and programs whose purpose is to meet those needs (16%). Though the percentages are low, in light of the fact that the respondents were asked to identify only their most significant learning – not all learning – I consider these results positive indicators. Specific needs noted by the respondents included: academic and social services support for at-risk children, aging-related issues (e.g., loss of independence, loneliness, loss of hearing), healthcare access (especially for the under- and unemployed), access to work and education for those who do not speak and understand English well, etc. They also specifically mentioned many of the agencies where they or their classmates were doing SL work, and/or organizations whose representatives had spoken to the SL seminars (e.g., a NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 5 local AIDS-care organization, free medical clinics, youthserving organizations, homeless shelters). These responses indicate an awareness of both the needs of, and the available resources in, the community. A relatively recent (2004) addition to the learning objectives of the Service Learning course was increased awareness of cultural diversity, and cultural competence in care. Twentythree percent (23%) of the respondents reported learning about cultural diversity and developing a greater cultural competence. The learning was both from the seminar part of the course (for which the students were required to read and report on information available at a website focused on cultural diversity in healthcare) and from the service experiences. One student, who was tutoring an adult learner of English, wrote that her experience “exposed [her] to another culture and someone that [she] might come across in a pharmacy setting.” A student who had worked with a very diverse population at a food and clothing distribution center reported that she had learned how “understanding a person’s personal and cultural background is one of the keys to enhance [the] relationship” with that person. The combination of classroom treatment of this subject, and experiencing the issues in practice, seems to have resulted in positive learning experiences. As noted above, at the end of the course, the students’ onsite supervisors were asked if, from their observations, the students learned through providing service. The response choices were: (a) a lot, (b) some, (c) a little, (d) nothing, (e) don’t know. Of the respondents, 94% indicated that their students had learned much (68%) or some (26%). Most of those who responded otherwise noted poor attendance or poor attitude issues with the students involved. Though the question posed to the supervisors was rather general, the responses indicate a quite positive assessment of the students’ learning, in terms of what the supervisors would like the students to learn. Conclusion What I have shown above is the basic design of a course that employs service-learning (learning objectives, assessment methods and teaching and learning activities), and how such a course can lead students to achieve significant learning through engagement in the community. Though I have described a course for pharmacy students to illustrate course design and the associated educational outcomes, I submit that this is equally applicable in other disciplines and in other settings. Engagement in service activities in a local community, coupled with appropriate reflective activities, can lead students to significant learning relevant to many disciplines. One can imagine the relevance of the learning I have noted above in the fields of communication, sociology, psychology, and other healthcare professions. By selecting different service work, one could imagine relevant learning in environmental science, civil engineering, criminal justice, etc. The service-learning literature is full of examples in a wide variety of disciplines. Service-learning is not an appropriate pedagogy in every course, but if we think of it as one of the instructional methods in our ‘tool box,’ we can employ it as needed. We can do so with the confidence that it has the ability to lead our students to significant learning. Reciprocal Mentoring Mathew L. Ouellett, Director Center for Teaching, University of Massachusetts Amherst Susan E. McKenna, Director of the Office of Research Literacy, Commonwealth College, University of Massachusetts Amherst Technological advances in higher education in recent years have provided wonderful new avenues for enhancing teaching and learning. These advances range from coursebased learning management systems to the increasingly available online data and reference sets in libraries. Nearly ubiquitous web access for most students allows them to call up images, videos, pod casts, news reports and websites dedicated to a myriad of issues. Indeed, as more and more students access and make use of materials via the internet, librarians, faculty and instructional staff across the disciplines see a concomitant rise in their need to help students better critique the day-to-day use of such resources. Educational developers are now regularly confronted with the question of how to we help prepare instructors to aid students in building the skills needed to distinguish between and make appropriate use of the array of resource materials now available to them related to their scholarly 6 NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 interests. The reality is that today many of our students are already more comfortable with the on-line environment than will ever be many of their instructors. Tom McBride’s (2007) annual “Beloit College Mindset List” helps us illuminate this disparity in how we seek and use information by pointing out that for the entering class of 2007 (students who will graduate in 2011, if all goes well): • Thanks to MySpace and Facebook, autobiography can happen in real time. • Most phone calls have never been private. • They get much more information from Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert than from the newspaper. • They're always texting 1 n other. • Avatars have nothing to do with Hindu deities. Interest in research literacy has provided a unique opportunity for collaboration between the Center for Teaching (CFT) and the Office of Research Literacy, located at Commonwealth College, the Honors College at the University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMA). We have joined together in a new collaboration across academic departments and functions in support of improved methods of faculty development – with a specific focus on helping instructors be better prepared to teach students research literacy. In this article we describe how our shared interests in faculty and instructional development merged in support of our new program to create an opportunity for collegial peer-mentoring. We describe our particular interest in and attention to helping instructors articulate the nuances of seeking information within their disciplinary contexts and how to teach students these methods and conventions in the ever changing context of technological advances. Communities of Learning The Center for Teaching (CFT) at UMA grew out of a desire among faculty and administrators to provide support for teaching at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. It evolved under the guidance of the Office of the Provost from the Lilly Teaching Fellows Program first hosted on campus in 1986, and was formally established in 1989. We report to the Provost’s Office and are advised by the Faculty Senate Council on Teaching, Learning, and Instructional Technology. The purpose of the CFT is to offer opportunities for professional development in teaching. Our services are wide-ranging: consultations with individual faculty and departments; annual award programs; teaching assistant (TA) training and support; yearly campus-wide events; resource development and distribution; and research and funded grants. In delivering these services to a diverse client group including faculty, TAs, departments, schools, colleges, and academic administration, we are guided by five primary goals: • To provide opportunities for professional development in teaching to faculty members and TAs to enable them to promote student learning. • To develop a variety of ways to share the talent, energy, perspectives and expertise of the instructors at this University • To increase communication about teaching and student learning both within and between departments and colleges. • To link the University and it’s instructors with programs and experts on teaching and learning at other campuses and organizations throughout the state, region, and nation. • To offer recognition and reward for excellence in teaching. Conventional approaches to mentoring in the past have been steeped in notions of hierarchical and unidirectional relationships and, often, the most successful of such relationships tended to be relatively private ones, occurring on a one-to-one basis (de Janasz & Sullivan, 2003). Working from a very different set of values, the CFT has for over the past twenty years, successfully guided faculty communities of learning, addressing issues such as junior faculty development, diversity, teaching with technology, and assessment. In all of these efforts, CFT efforts have prioritized the development of collegiality, shared leadership, open dialogue, and the deliberate welcoming of diverse perspectives. In our ongoing assessment efforts, for example, List (2003, 1997) found that over time participants report that their experiences with the Lilly Program had significant positive effects on teaching skills and attitudes, collegiality, research and service. When our colleagues in Commonwealth College decided to embark on the creation of a faculty learning community focused on research literacy, they came to the CFT for advice, resource materials and organization templates. We were glad to respond positively and what emerged from our collaboration was a unique mutual mentoring experience. While each office has its own mandate and priorities, we share a commitment to creating the highest quality educational development opportunities for colleagues across the institution. The Research Literacy Fellows program is an example of how we as colleagues have come together to work collaboratively and as peer mentors to blend proven educational development strategies to address an innovative, fast changing topic. Research Literacy Fellows The Office of Research Literacy, located at Commonwealth College, the Honors College at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, works in partnership with faculty to improve undergraduate research skills and to provide a collaborative bridge to campus-wide resources. Research Literacy promotes faculty development through the Research Literacy Fellows and through providing concrete resources for faculty to use in their teaching as well as practical tools for students to use in their coursework. Initially conceived as a preventative response to concerns about plagiarism, Research Literacy has evolved into a multi-pronged approach that pulls together these elements – academic integrity, information technology, cross-disciplinary analysis, and diversity and social justice – with specialization in how research can be employed in community- and creative-based courses. That multi-pronged approach is expressed through the reciprocal mentoring model that structures the Research Literacy Fellows. Continued on page 8 Our hands-on resources include research tools with “how-tos” for evaluating sources, generating research questions, and writing research logs and literature reviews. Our Library Database Research Guide organizes the University of Massachusetts academic databases into a format with discipline specificity that can be easily used by undergraduates. Our series of Resources for Researchers also include assignment templates for using the Library Research Guide and samples of student work. NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 7 Funded in 2005-06 by the Graduate School Ethics Council, and in 2006-07 and -08 by Commonwealth College, the Fellows program was conceived as an opportunity to develop mentoring relationships between faculty and graduate instructors who would work together on incorporating the conceptual and practical frameworks of Research Literacy into their teaching. Early on in the grant application process we, the authors of this article, met regularly to review the successful attributes of the CFT’s long standing faculty and graduate student learning communities. These communities include: the Lilly, Teaching and Learning in the Diverse Classroom and TEACHnology Fellows programs, as well as the Grants for Professional Development in Teaching, part of the Periodic Multi-Year Review (PMYR) which is our campus wide review process for tenured faculty (Sorcinelli, et al, 2007). Because all educators are impacted by the changing terms of research ethics and information technologies, we began with the belief that through reciprocal mentoring fellows would learn from one another with the by-product of more opportunities for professional socialization, especially for junior faculty and graduate student instructors. Patterning the Research Literary Fellows program on prior efforts developed by the CFT, we were guided by the shared belief that a community of practice model, in this case focused by reciprocal mentoring, redistributes the responsibility for learning, advances collaborations across the disciplines and fosters meaningful and sustained intra-institutional dialogues across campus departments, offices, and resources. The selection process for the ten 2005-06 fellows was extremely important and we actively sought to create an exciting and diverse group that included tenured and contract faculty as well as graduate instructors with a range of cultural backgrounds, teaching experiences, and interdisciplinary research interests that would generate valuable juxtapositions. For instance, one fellow, who was completing a Master’s degree in using information technology in the classroom, brought a colloquial ease to our discussions about crossing the “tech barrier.” That everyday confidence was confidence building for another individual who with over thirty years University teaching experience was extremely insecure about using technology pre-fellows: “I am so thrilled that I lost my fear of the computer, that I lost my fear of searches.” Several fellows with strong interdisciplinary training in critical cultural studies had particular viewpoints about the meta-question of how to make connections between theory and practice, while other fellows spoke about the hands-on application of academic research through including community service learning components in their teaching. Reciprocal mentoring effectively leveled the playing field; although senior faculty had years of teaching and research experience, other participants brought divergent competencies and perspectives to our meetings. The programming for the Fellows’ year – a one-day Please take a look at the UMASS online resources at: http://www.comcol.umass.edu/academics/researchliteracy/ 8 NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 retreat and eight monthly meetings – generated an additional level of reciprocity between the Fellows community and campus resources. While several meetings focused on fellow-to-fellow conversations about teaching challenges and successes, we also organized meetings as participatory workshops that featured guest contributors. We built upon our already established alliances with campus resources to include discussions about promoting academic integrity with University ombudsperson, Catherine Porter, using technology to improve teacher-student interactions with Associate Director for User Services at the W.E.B. Du Bois Library, Anne C. Moore, and utilizing research as a tool for incorporating cultural diversity into curricula with Information Literacy Librarian, Isabel Espinal. These participatory workshops included demonstrations of resources such as academic databases as well as discussions of issues involved in teaching research skills. Incorporating both practical and theoretical content encouraged interactions across disciplines while simultaneously demystifying campus resources such as library subject specialists and workshops for faculty offered by the Office of Information Technology. These meetings expanded upon the dynamics that transpired fellow-to-fellow to include reciprocity across campus as participants from both sides reported positively upon the opportunity for networking and feedback with future collaborations envisioned. As we move into 2007-08, the third year of the Research Literacy Fellows, the model of reciprocal mentoring has broadened at several levels. First off, at the institutional level, the underlying philosophy of an honors college to serve as a testing ground for innovative pedagogical Example of reciprocal mentoring from fellows to administration to students that disrupts traditional compartmentalization of University: Another dimension of reciprocal mentoring can be found through the inclusion of administration and professional staff in the fellows program. One administrator who works in program development for recruitment and retention of ALANA students described how the fellows experience impacted her work with students. Such dissemination examples suggest that the reciprocal mentoring structure of the Fellows program maximizes the institutional potential of Research Literacy through the sharing of practical resources and tools that move across the traditional University hierarchy for teaching and learning. dissemination is upheld by the College’s support of the Research Literacy Fellows.i The Fellows’ program is now open to faculty members from across the campus and our total number of participants to date is thirty-four. Moreover, several fellows have been members of the University professional staff and administration: the 2007-08 group includes a reference librarian and our University Ombudsperson intends to participate in the future; we have also included an undergraduate fellow whose contributions have been characterized as “invaluable.” The expansion of the previous Commonwealth College-affiliated selection pool has greatly added to reciprocal mentoring across disciplines and departments and has been a key aspect of the potential for a reconceptualization of the traditional hierarchy of institutional responsibility for learning at the intrainstitutional level. For example, a central focus of the Fellows’ year is the emphasis on using research assignments as vehicles for incorporating questions about diversity and social justice into course materials. Last year, fellows from three different departments – Legal Studies, Communication, and Comparative Literature – discovered they were all using the timely question of immigration as a central teaching focus. That cross-disciplinary intersection illustrated the sharing of teaching resources through conversations, which, as one participant commented, “linked me to other departments for information.” The variegated approaches that individual fellows brought to diversity education were particularly significant components of the reciprocal mentoring experience as interdisciplinary debates and cross-national perspectives moved into practical suggestions. Such topics as the interrelations of stereotyping and plagiarism were a mutually beneficial conversation for both the fellows and the Faculty Senate Ad Hoc Committee on Plagiarism whose members presented at a fellows seminar on academic integrity. ii A discussion of the politics of making diversity more visible on the library home page offered concrete suggestions that may prove to be fruitful for future library initiatives. These instances of reciprocal mentoring – across faculty-to-faculty and department-to-department as well as office-to-office and resource-to-resource – point to the multiple dimensions of intra-institutional reciprocity occur through the Research Literacy Fellows initiative. Outcomes In before and after assessments, participants reported significant improvement in their own skill at evaluating sources and navigating academic databases as well as in their understanding of plagiarism and copyright. Learning through teaching reflects a basic mandate of critical pedagogy: that the presuppositions of one’s own research and writing become more explicit when put into practice in the classroom. Participants who were PhD candidates were particularly affirming about their increased skill at writing literature reviews as a result of the fellows’ year. Moreover, fellows stated that their confidence in teaching research methods and ethics appreciably increased as almost 100% reported that they now require students to use online Research Literacy resources. That confidence was reflected in multiple observations about how student research skills had improved by the end of the fellows’ year. Of note in pre- and post-assessment was the report of increased incorporation of perspectives on diversity and social justice into classroom materials. That change reflected a particular goal of the fellows program: to meet the growing need for critical resources and practical tools that could be utilized to diversify course readings and research assignments. Our preliminary assessment also indicated that faculty usage of such campus resources as the library subject specialists and OIT resources increased considerably. Additionally, the fellows program raised awareness of resources such as the new Library Learning Commons and the Office of Community Service Learning. Last, and in continuity with the initial motivation for a model of reciprocal mentoring, fellow-to-fellow collaborative interactions were affirmed through statements about the importance of the “chance to feel part of the ComCol community” as “peer discussion and learning together” made the fellows’ year “a very rewarding experience and an important one for community-building.” Example of intra- and inter-institutional dissemination: A really good example of reciprocal mentoring in the Fellows program that circulated across both intra- and inter-institutional levels can be found in the dissemination of one of the key skills suggested by Research Literacy. The research log, first suggested by reference librarian Isabel Espinal, is a record of the research process that emphasizes source evaluation and citation. Already in wide usage at Commonwealth College through the innovative Dean’s Book Course, fellows have remarked upon the usage of the log in several additional contexts. A fellow in the 2006-07 cohort, an assistant director of the University Writing Program, told us they are considering using the research logs in their teacher training, which will potentially impact all incoming students taking a first year writing course. Other fellows have taken this resource for undergraduates into their teaching of graduate students. Moreover, because the fellows are open to part-time faculty and graduate instructors who regularly teach in other departments and colleges, we hear anecdotally that the research log is in the process of being disseminated across campus and beyond. NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 9 Conclusion As we have indicated above, early assessment of the Research Literacy Fellows Program indicates that this is a promising model for preparing instructors across the disciplines to teach better and to know better how to coach undergraduate and graduate students, as well as peers, in the central tenants of research literacy. We are particularly excited about having found another successful strategy to manifest our institution’s commitment to inclusive teaching and learning. In addressing and discarding traditional models of mentoring and academic program administration, we have also found a new opportunity to embrace a collegial and mutually beneficial approach to the development of institution wide instructional and faculty development programming on our campus. Bibliography de Janasz, S., & Sullivan, S. (2004). Multiple mentoring in academe: Developing the professorial network. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64, 263-283. List, K. (1997). A Continuing Conversation on Teaching: The Lily Teaching Program at UMass 1985-96. In D. Dezure (Ed.) To Improve the Academy, 16, 201-224. Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press. List, K. (2003). The “Conversation” Continues: UMass Lilly Teaching Fellows Program Builds on First Ten Years. Journal of Faculty Development, 19, (2), 57-64. Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press. McBride, T. (2007). The Beloit College Mindset List. Downloaded September 18, 2007 from http://ctl.stanford.edu/Tomprof/postings/809.html. Sorcinelli, M. D., Shih, M., Ouellett, M. L., & Stewart, M. (2007). How post-tenure review can support the teaching development of senior faculty. In D. Robertson (Ed.), To Improve the Academy. (25), pp. 280-297. Bolton, MA: Anker. i Commonwealth College is in a unique position for dissemination because we maintain an interdisciplinary make-up in our pool of instructors, course offerings, and student populations, and have non-traditional interdepartmental relationships, which include honors courses and honors faculty liaisons in all departments campus-wide. Moreover, the College’s educational opportunities for faculty, graduate instructors, and part-time lecturers and our alliances and collaborations with campus resources provide established mechanisms for dissemination. iiThe Research Literacy Fellowship programming expanded in 2006-07 to include two seminars a year that are open to the wider campus teaching community. Each seminar had approximately forty attendees. Helpful Suggestions for Teaching Interactive Television Courses Laura Donorfio Assistant Professor of Human Development and Family Studies University of Connecticut, Waterbury Catherine Healy, Instructional Designer University of Connecticut, Storrs The Team: Keith Barker, Director, Institute for Teaching and Learning Dan Mercier, Assistant Director, Institute for Teaching and Learning Steven Fletcher, Manager of Interactive Television & Video Conferencing Distance education has rapidly evolved and grown since it first began in the United States in 1883 with courses delivered by mail. And it is only expected to “boom” with the recent decision by the U.S. Congress to relax the “Fifty-fifty” rule that has required accredited colleges and universities to limit the number of off-campus students enrolled in distance education programs to under fifty percent. The University of Connecticut (UConn) has also rapidly evolved and grown in this area, spending considerable resources building the pedagogical and technological infrastructures for delivering one of the newest and fastest growing instructional media in distance education, two-way interactive television (iTV). This medium is distinctly different from earlier efforts because of its “real time” interactive capacity between two or more sites. Our team first began its venture back in 2005, with the overall goal of being able to increase the number of students taking introductory courses 10 NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 with core faculty members. As is the case with many institutions, instructional resources are spread thin among regional campuses, limiting the courses that could be taught in any given semester. When the decision was made to go ahead and convert a traditional course into an iTV course, many unexpected intricacies and challenges surfaced along the way. The following will provide some helpful suggestions when developing and teaching an iTV course. Initial steps involved gaining support from all the necessary levels of UConn to teach a course in this manner (the department with which the course was offered, the Vice Provost’s office, UConn’s Institute for Teaching and Learning (ITL), and each of the campuses involved) and creating a core team to prepare and launch the course. The core team was comprised of the course professor as the content expert (first author), an instructional designer for pedagogical support and re-design (second author), and an iTV technology expert. As our team worked to re-design a single site adult development and aging course into a three site adult development and aging course, we realized that several elements were integral in making the course a success. The most important elements were: pedagogical considerations, most effective course platform, most effective use of technology, effective training for all those involved, and student comfort and background with iTV. In addition to addressing each of these elements, Table 1 provides a list of general dos and don’ts to keep in mind when designing and teaching an iTV course for the first time. Pedagogical Considerations: Our main pedagogical focus was to ensure the objectives, assessments, and activities all aligned and were appropriate for the method of delivery. Many of the in-class activities had to be adjusted to be effective across three sites. For example, during lectures in the single-site version of the class, the professor would often write on the white board to emphasize teaching points. In the iTV environment, writing on a white board is very difficult to read at the remote sites due to the glare. The professor had to ensure the visual component of the lecture was included in her PowerPoint presentation instead of spontaneously writing on the board. Some adjustments required moving activities from in-class to an out-of-class format. An online course management tool was added to the course to facilitate out-of-class activities, such as asynchronous course discussions. This had the added benefit of helping to create a sense of community. In addition, the online course management tool afforded students easy access to class materials such as handouts, assignments, and supplemental materials. Course Platform: Many variables went into consideration when deciding what the most effective course platform would be for teaching an introductory course on adulthood and aging. Both authors felt face-toface contact was integral not only for effective teaching, but also in building a better relationship between the subject matter and the students. Because three of the campuses are within 45 to 60 minutes of each other, the instructor was willing to build a rotating schedule, meeting with each campus at least three times during a 14 week semester. Weekly PowerPoint handouts were provided, summarizing the class lectures so the students could more easily follow from the remote sites. One teaching assistant was handpicked and assigned to each site, each having had the course before so they were comfortable with the instructor, the course content, and primarily, to operate the equipment and manage the class when the instructor was not there. Lastly, as shared above, an on-line course management tool was implemented for weekly discussion assignments, so students could read and react to other students at other sites. Technology: The technology used to deliver the iTV course consisted of an H.323 videoconference system located on the main campus. Because there were more than two sites, a bridge or multipoint control unit needed to be used. Each site had a teaching station in the front of the class with a control panel, document camera, VCR, DVD player, computer, and Internet access. Each class also had a large white projection screen in front (middle) of the class, plasma screens in the front (sides) and back and microphones strategically mounted in the ceiling. Based on student feedback, two significant adjustments were made during the semester to improve the delivery of the course to all sites. The first adjustment involved muting the remote sites until they were addressed or had questions or comments. Because the system is voice activated, any remote conversation, background noise, or even laughter would overpower the instructor, causing her site to become mute. The second adjustment involved changing the way the equipment could send and display instructor, class, and content images. Initially, only one image could be sent and displayed to the remote sites at any given time, which meant the instructor could not be displayed when content (e.g., PowerPoint, Internet, document camera) was displayed. Consequently, the teaching assistants had to manage how long the content was displayed versus the instructor and this required a switch and focus with every instructor/content switch. Not only did the students feel this took away from the class flow, but they also wanted to see the instructor at all times. To help solve this complaint, equipment and technical changes were made so two images, the instructor and content, could be sent and displayed to the remote sites at the same time. Training: Effective training was an important factor in the success of the iTV course. Everyone involved with course delivery was trained on the operation of the equipment. This included the professor, the three teaching assistants, and the students. Training consisted of one-on-one sessions to acclimate the users to the capabilities of the iTV system and correct operation of the equipment. Training included procedural information on camera focus and zoom, microphone operation, source switching, and classroom management tips. This was followed by practice sessions to reach proficiency. In addition, several mock teaching sessions were conducted to enable the professor to adjust her teaching style and techniques to the unique requirements of distance teaching. With respect to the students, each student was provided with a Distance Learning Handbook that addressed common concerns and offered tips on succeeding in an iTV course. The handbook also included information on successfully using the online course management tool associated with the course. This was followed by in-class demonstrations to reinforce student procedures. Student Comfort and iTV Background: Many challenges emerged while teaching the course. An unexpected challenge involved creating a comfort with the technology and the equipment in the room. This was much more difficult to achieve than imagined. Not only did we need to focus on the human elements but the technological elements as well. Another challenge centered on building a trust with the technology, especially the on-line management tool. For many of the students, it was not only the first time they took an iTV course but it was the first time they had to use an on-line management tool. Another challenge involved student’s comfort asking questions and participating when the instructor was not at their site. To remedy this, the instructor decided to have the teaching assistants facilitate individual discussion sessions at each of their respective sites before discussing as a group. Fortunately, addressing the challenges throughout the term by administering on-line surveys proved to work very well overall, as evidence by student feedback and evaluation scores. In summary, while developing and teaching a distance education course does take more time and require more resources at the onset, it can be a tremendous resource if it matches the needs of the course content, the instructor, and the students. It offers many benefits such as reaching more students across campuses, providing a class that no faculty member was available to teach, being cost effective in the long run, and providing a competitive edge in attracting more students. With the growth of distance education and technology, and in our never-ending quest to meet the growing needs of our students, distance education is a necessary option for most educational programs. References: Donorfio, L.K.M. & Healy, C. (in press). Teaching an interactive television course in adulthood and aging: Making it happen. Educational Gerontology. Gerontology News (2006). The Gerontological Society of America, Washington, D.C. (April, p.7). Continued on page 12 NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 11 Table 1. Interactive Television Course Design Dos and Don'ts* Dos Pedagogy • Make sure subject material lends itself to Distance Learning (DL) “iTV”—sensitivity of subject, intro class needing maximum “face time” • Construct course with the help of the instructional design team (creating ITV friendly objectives) • Give students a PowerPoint style handout covering main points of lecture so they have something to follow where you are more quickly and to write notes on • Realize more prep time is needed • Realize teaching takes more time in this format--build in at least one extra week for catch-up • Bring “real experiences” to the course (not just simulation) • Try to create a “virtual classroom” Technology Pedagogy • Have the course be a writing (W) course or letting it turn into one • Think a traditional classroom course taught could be easily converted to an iTV course • Have class time consist of only lecture(s) (kiss of death for students and you) • Change topic(s) to be covered without at least two weeks prior notice to students • Assume all sites/campuses are created equal with following your class sessions (all sites do progress differently) Technology • Form a partnership “team” with instructional design and IT department • Make sure your university has broadband connectivity • Own a notebook computer you take with you to each site (as well as a flash drive) containing your presentations/handouts/ exercises • Make sure computer lab is open and available to traditional as well non-traditional students (not banking hours) • Do think up backup class sessions and/or activities if technology does not work properly • Training – make sure you and TAs are trained via all aspects of technology to be used • Think you can facilitate a class session by yourself without a T.A. at your site to save money • Have students rotate being T.A. for the day (this takes away from their learning) • Assume all students have a cutting edge computer at home • Assume all students have used a computer • Assume all sites/campuses are equal with respect to technology (what it has, support and service) Logistics • Have a staff or fellow faculty member proctor exams (in addition to T.A.) • Allow eight full months to plan DE course – if you are given a course release allow four full months • If using an online course management tool, such as WebCT Vista, request and start to populate four full months in advance • Choose TA’s for each site who are trained in the subject matter and the technology • Set-up mock lecture sessions (more than one) with all those involved at all sites. • Visit each campus (prior to teaching) to experience classroom, computer center, bookstore • Provide all handouts for class at least 24 hours prior to in case student do not have a computer at home • Have student sign-in sheet for each site • Have a basic understanding for each site regarding composition and knowledge. • Have cell phone numbers for each T.A. and at least two students in each class in case communication is interrupted or cut off • Be available via phone and email with rules about the use of each • PowerPoint presentations work best with a dark background, light text, and font size of at least 24 point • Speak at a moderate pace and volume • Minimize distracting habits on camera Logistics • Assume all sites are created equal with regard to composition, dynamics of group, and ability to get along as a group • Have a free for all, letting any site talk at any time—go around to each site periodically asking for questions and comments and have T.A. cut in when immediacy is needed • Think overall time is equivalent to a traditional “face-to-face” class—DE is estimated to take two to three times longer • Assume registrar indicates course is a DE or iTV course—check! • Skip a site if class is cancelled. Students are short changed at that site and are quick to tell you so! • Wear white or patterned clothes for this affects student viewing at the remote sites Department Support • Make sure they understand DL/iTV • Make sure they support your teaching it in this format (takes more time and needs more support) • Sell (constantly) the positives of DL/iTV • Accept and try to appreciate differing viewpoints of those who are pedagogically against using iTV methods *Taken from Donorfio & Healy (in press). 12 Don’ts NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 Department Support • Assume your department knows what DL or iTV is • Assume colleagues like DL or even see it as a viable option (conducive to learning) • Assume colleagues are happy for you embarking on this mission (many times they worry that because of your precedent they will be asked to teach in this manner) Meet Our New Board Members: Michelle Barthelemy Coordinator, Distance Learning Greenfield CC 1 College Drive, Greenfield, MA 01301 Phone: 413-775-1481 BarthelemyM@gcc.mass.edu Donna M. Qualters, Ph.D. Director,Center for Teaching Excellence Associate Professor, Education and Human Services Suffolk University 8 Ashburton Place Boston, MA 02108 Tel: 617-570-4804 e-mail: dqualters@suffolk.edu Mei-Yau Shih Associate Director Center for Teaching University of Massachusetts Amherst 301 Goodell Building 140 Hicks Way Amherst, MA 01003-9272 Phone: 413-545-5172 mshih@acad.umass.edu Michelle Barthelemy was hired in May of 2005 as Coordinator of Distance Learning/Instructional Technology under a Collaborative Title III Grant with Berkshire Community College. The goal of the grant is to establish an online associates degree in Liberal Arts with an education concentration. Under the grant, she is responsible for coordinating the development of online courses and assist faculty in developing and delivering online courses. As a result, she organize trainings and workshops for faculty that focus on the technical and pedagogical use of technology in face-to-face, web-enhanced and fully online courses. In addition, she develops how-to training materials for faculty and students. Over the past couple of years, the support she offers has extended to meet the needs of the students at GCC. Some students who are new to taking an online class may need additional support ranging from setting up their browser to be compatible with the learning management system GCC uses managing their time when taking an online class. With the assistance of faculty and the staff in the Center for Teaching and Learning, she is working towards developing training sessions and tutorials to help students succeed in online classes. Dr. Donna Qualters is the founding director of the Center for Teaching Excellence at Suffolk University and Associate Professor of Education and Human Services teaching future public school teachers. She has been involved in faculty development for over 15 years at a variety of schools including Northeastern University, MIT, UMass Medical School and Endicott College. Her research is in the area of creating faculty community, change in both individuals and institutions, and of course teaching/learning. Her passion is engaging faculty in communities of practice so as to share ideas, grow as professionals, and understand both the art and science of teaching to create vibrant learning environments for students. Dr. Mei-Yau Shih is Associate Director of the Center for Teaching (CFT), University of Massachusetts Amherst. She is responsible for identifying, developing, and overseeing campus-wide teaching technology services through the Center for Teaching. She has consulted with hundreds of faculty members on integrating instructional technologies into their teaching; she has also conducted a variety of assessments for both online and regular classroom teaching. She sits on campus and university system advisory and governance councils that set practices and policies for effective use of instructional technology. Currently, in addition to CFT’s duties, Dr. Shih is also an Adjunct Associate Professor of Educational Technology in the Department of Teacher Education and Curriculum Studies of the University of Massachusetts, where she teaches a graduate course every year, serves on doctoral dissertation committees, and oversees various independent studies. NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 13 Connecting With Others There are two dominant national organizations—POD and NCSPOD--of people who do faculty development work. Both have excellent fall conferences, with many sessions appropriate for faculty members interested in professional development. The Professional and Organizational Development (POD) Network in Higher Education is primarily four-year college and university professionals. Link up with POD at www.podnetwork.org. POD also has a very active and informative listserv. William Penn Hotel Pittsburgh, PA October 25-28, 2007 You are enthusiastically invited to be part of the 2007 POD Conference. This 32nd annual meeting will offer many opportunities for professional development and renewal. The theme, "Purpose, Periphery, and Priorities," underscores POD's commitment to accessible research, professional growth, and improved teaching and learning. The National Council for Staff, Program and Organizational Development is an affiliate council of the American Association of Community Colleges, and is primarily two-year college professionals. Link up with NCSPOD at www.ncspod.org. There are also many regional associations like The Collaboration for the Advancement of College Teaching and Learning. The Collaboration (http://www.collab.org/) presents two major conferences each year, each of which brings together faculty, student affairs personnel, administrators, and staff to discuss issues of teaching and learning. These events, held in November and February in Bloomington, Minnesota, feature keynote speakers of national and international renown as well as presenters from Collaboration institutions. UPCOMING CONFERENCES November 16-17, 2007, Collaboration conference "PROMOTING DEEP LEARNING: CULTIVATING INTELLECTUAL CURIOSITY, CREATIVITY, AND ENGAGEMENT IN COLLEGE" February 15-16, 2008, Collaboration conference "CRITICAL THINKING IN THE AGE OF THE INTERNET" WWW.NEFDC.ORG Have you visited the NEFDC web site lately? It is maintained by Board member Rob Schadt from Boston University. Information on the annual fall conference and the Spring Roundup for Faculty Development Professionals, contact information for the board, membership forms, and related data are all available online. Take advantage of this valuable resource and bookmark us at www.nefdc.org 14 NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 NEFDC Fall Conference DCU Center, Worcester MA November 9, 2007 Attendance will be limited, so advanced registration is recommended. No refunds will be given, but substitute registrations will be accepted. Early Registration (postmarked by October 13th) Members: $60.00 Non-members: $95.00 Students: $25.00 General Registration (postmarked after October 13th) Members: $80.00 Non-members: $115.00 Students: $25.00 Membership: Individual: $35.00 Institutional: $150.00 NOTE: Check your Institutional Membership at http://www.nefdc.org/members.htm Please submit one registration form for each participant. Name:_________________________________________________________ Institution: ______________________________________________________ Address: _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Work Phone: ____________________________________________________ E-mail Address: __________________________________________________ Make checks payable to NEFDC (Fed ID#: 04-3422583) Mail completed registrations with payment to: Tom Thibodeau New England Institute of Technology 2500 Post Road Warwick, RI 02886 NEFDC EXCHANGE • FALL 2007 15 NEFDC EXCHANGE Tom Thibodeau, Assistant Provost New England Institute of Technology 2500 Post Road Warwick, RI 02886 NON PROFIT ORG U.S. POSTAGE PAID PROVIDENCE, RI PERMIT NO. 267 Fall Conference Nov. 4, 2005 – Beyond Tolerance: Diversity and the Challenge of Pedagogy in American Higher Education Board of Directors The fifteen members of the Board of the NEFDC serve staggered three-year terms. Board Members are available for and welcome opportunities to meet and consult with members of the NEFDC and others who are interested in faculty development. We welcome nominations and self nominations for seats on the Board. Members Whose Terms Expire in June 2008 Jeanne Albert, Professor of Mathematics Castleton State College Seminary Street, Castleton, VT 05735 (802) 468-1308 email:jeanne.albert@castleton.edu Elise C. Martin , Director, Instructional Design and Curriculum Projects Office of Instructional and Professional Development Middlesex Community College Lowell, MA 01852 (978) 656-3288 martine@middlesex.mass.edu Judith E. Miller, NEFDC Board President Associate Dean for Special Academic Initiatives Corner House, 3rd floor Clark University 950 Main St., Worcester, MA 01610 508-793-7464, 508-421-3700 (fax) judmiller@clarku.edu Rob Schadt, Education Technology Manager Boston University School of Public Health 715 Albany Street, Boston, MA (617) 638-5039, (617) 638-5299 (fax) rschadt@bu.edu Susan C. Wyckoff, Vice President Colleges of Worcester Consortium 484 Main St., Suite 500, Worcester MA 01608 (508) 754-6829 x3029 swyckoff@cowc.org Members Whose Terms Expire in June 2009 Charles Kaminskim, NEFDC Treasurer Assistant Dean of Academic Affairs Business, Science & Technology Division Berkshire Community College 1350 West Street, Pittsfield, MA 01201 (413) 499-4660, ext. 272, (413) 447-7840 (fax) ckaminsk@berkshirecc.edu Michelle Barthelemy, Coordinator, Distance Learning Greenfield CC 1 College Drive, Greenfield, MA 01301 Phone: 413-775-1481 BarthelemyM@gcc.mass.edu Elizabeth Coughlan, Associate Professor of Political Science, Salem State College 352 Lafayette St., Salem, MA 01970 (978) 542-7296 ecoughlan@salemstate.edu Thomas S. Edwards, Past President of NEFDC Vice President for Academic Affairs Thomas College 180 West River Road Waterville, ME 04901 (207) 859-1350, (207) 859-1114 (fax) edwardst@thomas.edu Thomas H. Luxon, Cheheyl Professor and Director Dartmouth Center for the Advancement of Learning Professor of English, Dartmouth College 6247 Baker-Berry, Hanover, NH 03755 (603) 646-2655 www.dartmouth.edu/~dcal thomas.h.luxon@dartmouth.edu Donna M. Qualters, Ph.D., Director,Center for Teaching Excellence Associate Professor, Education and Human Services Suffolk University 8 Ashburton Place Boston, MA 02108 Tel: (617) 570-4804 e-mail: dqualters@suffolk.edu Members Whose Terms Expire in June 2010 Keith Barker, Associate Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education and Director of the Institute for Teaching and Learning University of Connecticut 368 Fairfield Way, Unit 2142 Storrs, CT 06269-2142 (860) 486-2686, (860) 486-5724 (fax) kb@uconn.edu Jeff Halprin, Past President of NEFDC Associate Dean Nichols College PO Box 5000 Dudley, MA 01571-5000 (508) 943-1560, (508) 213-2225 (fax) jeffrey.halprin@nichols.edu Mei-Yau Shih, Associate Director Center for Teaching University of Massachusetts Amherst 301 Goodell Building 140 Hicks Way Amherst, MA 01003-9272 Phone: 413-545-5172 mshih@acad.umass.edu Tom Thibodeau, Assistant Provost New England Institute of Technology 2500 Post Road Warwick, RI, 02886 (401) 739-5000 tthibodeau@neit.edu