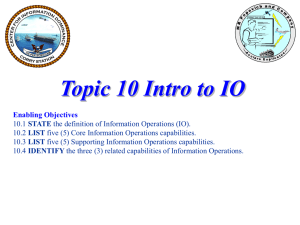

The Ingredients of Successful PSYOP

advertisement